by Yvonne Tan

As Najib Razak was found guilty of all seven charges, his supporters — also known on Twitterjaya as ‘kluster Bossku’ — gathered outside of Kuala Lumpur High Court chanted “Bebas Bossku”, “Bossku tak bersalah” with the fault lying in “Tun Mahathir Mohamad kejam”. Najib’s daughter (@yananajib) also took to Instagram, posting a picture of the crowd with the caption “A boss has a title. A leader has the people. 28.07.20. Your support means the world to us. Kami sekeluarga tak akan lupa. TQ kerana sentiasa bersama bossku. 😘😘”

As Najib Razak was found guilty of all seven charges, his supporters — also known on Twitterjaya as ‘kluster Bossku’ — gathered outside of Kuala Lumpur High Court chanted “Bebas Bossku”, “Bossku tak bersalah” with the fault lying in “Tun Mahathir Mohamad kejam”. Najib’s daughter (@yananajib) also took to Instagram, posting a picture of the crowd with the caption “A boss has a title. A leader has the people. 28.07.20. Your support means the world to us. Kami sekeluarga tak akan lupa. TQ kerana sentiasa bersama bossku. 😘😘”

What started out as a meme then appropriated for a political campaign, has come to encompass a wider “struggle” against the new government(s) emerging. Just as when Anwar Ibrahim was released after getting full pardon, supporters shouted “Reformasi!” as he left the Cheras Rehabilitation Centre in Kuala Lumpur recovering from a shoulder injury on the way to meet King Sultan Muhammad V to formalise the pardon in mid-2018, “Bossku” has become the opposing protest slogan.

It seemed as something frivolous and trivial back then, that a meme of Najib looking back at you while riding a black-and-red Yamaha Y15ZR 150cc, also popularly known as Ysuku, could become the rallying cry against disputing Najib’s 1MDB trial. Lest we forget, the Ysuku also has had a registration plate 8805KU spelling out “BOSSKU”. Many have disregarded his support base to be “Mat Rempits”, as they are not a group of people politicians regularly appeal to garner support. Linked to the working class, forming some sort of subcultural identity, Najib and UMNO have somehow managed to gain ‘anti-capital’.

Borrowing from Rachel Chan’s terminology of ‘anti-capital’ where non-conformity is celebrated, particularly against socially ingrained habits, [1] one would assume Najib would instead run counter to such countercultural identity given he is the epitome of status quo — royal ties, his father had founded the party that would rule Malaysia for 61 years. Nevertheless, UMNO’s support for Mat Rempits have always been apparent wherein Khairy Jamaluddin and Abdul Azeez have been sympathetic to their cause all the way back in 2009. [https://thenutgraph.com/umno-and-the-mat-rempit/]

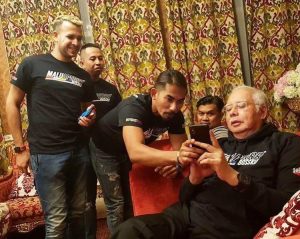

It did not take long for Bossku to achieve to reach popular culture status riding on this loose idea of slogans surrounding “Bossku”. Utilised in rap music such as Kalam Biru’s “Malu Apa Bossku”, he criticizes the then Pakatan Harapan government for not fulfilling their promises and defends Najib’s credibility, rapping “malu apa bossku, beri fakta bukan palsu”. “Malu apa bossku” is the phrase that started it all in the viral selfie video of Najib’s reply with a man calling out “Boss kita!”

Another incredibly popular song with 18 million views at the time of writing, MeerFly featuring Tuju, SoMean, MK I K-Clique “BossKu” was released in April 2019. The song did not reference anything in particular to Najib beyond the hook which goes “Malu apa bossku / Bossku, bossku, bossku, bossku” and its lyrics are typical of popular rap with braggadocious lyrics like “that booty lagi thick dari Nike/ And I’m lovin’ it / Tapau balik macam McD/ Lambo that body bomb terpaksa ghini”. Although devoid of explicit political statements, many in the comments express support for Najib and how the song is a great embodiment of their sentiment, with some mentioning how listening to the song could get them fired.

Again, there is an underlying sentiment of rebelliousness against an unjust order by making light of the seriousness of the 1MDB scandal. This sort of underplaying or “trivialisation is a style of discourse dominated by ideas, slogans, intuitions, and other more or less familiar shortcuts, instead of evidence, logic, or coherent reasoning. As a result, we have answers to moral, cultural, social, and other matters before the questions are even posed. There is thus not much use for a dialogue, or a search for truth which the actors can easily find in their trivialized phraseology.” [2] Speaking of the manner it is trivialised, the name “Bossku” or “My Boss” immediately feels like a contemporary, viral version of Chandra Muzzafar’s “protector-protected” bond.

Again, there is an underlying sentiment of rebelliousness against an unjust order by making light of the seriousness of the 1MDB scandal. This sort of underplaying or “trivialisation is a style of discourse dominated by ideas, slogans, intuitions, and other more or less familiar shortcuts, instead of evidence, logic, or coherent reasoning. As a result, we have answers to moral, cultural, social, and other matters before the questions are even posed. There is thus not much use for a dialogue, or a search for truth which the actors can easily find in their trivialized phraseology.” [2] Speaking of the manner it is trivialised, the name “Bossku” or “My Boss” immediately feels like a contemporary, viral version of Chandra Muzzafar’s “protector-protected” bond.

It is beyond rejecting a leader such as #NotMyPM, but rather there is an implication that one is not only under Najib, but also secured or safeguarded by him. Hence, such allegations are deemed ludicrous and simply treated as unimportant when operating by the logic of the bond. “Malu Apa Bossku” also suggests a fervent trust in the ruling political figure matched with a deep-seated scepticism against institutions out to get him. The personalisation also ties Najib’s wellbeing to oneself. Muzzafar argues this “protector” rhetoric is propped up by “unquestioning loyalty is something that a Malay protector expects from the Malays and from UMNO in return for what he sees as the political, economic, cultural and psychological protection provided to the community and the party. It is, in other words, a relationship within the community. In itself it cannot be defined as a communal relationship; it is merely a community-based relationship.”

Hence, we ask what specific community is behind “Bossku”? With the common trend from “Bossku” as a meme, gaining popularity in rap music and also expressing mat rempit culture, it shows much of Najib’s support base is also the youth, challenging the normative idea that his supporters were only made up of older people who are used to the status quo. Recalling Najib’s predecessor, Badawi and his speech on Islam Hadhari, he also mentioned “the youth… are an invaluable asset with tremendous potential. Their views are very important in formulating national policies […] All parties must be resolute, unwavering and committed in ensuring the success of the agenda to strengthen the Malay race.” [3] Clearly expressing that Malay Muslim youth are a means for maintaining UMNO’s rule, it is only fitting that they represent the hopes of those in power, especially evidenced by the special role carved out for them. “Bossku” is but a glimpse into emerging Malay Muslim identities that are not necessarily considered mainstream, that call for the reinstatement of UMNO and Najib’s innocence. From Bunkface’s first political song “Akhir Zaman” to emerging “Darah dan Maruah Tanah Melayu” heavy metal movement, the unfolding of traditionalistic subcultures that calls for the continued protection of an elite-centered status quo is not limited in the halls of Putrajaya.

[1] Chan, Rachel Suet Kay. 2017. Ah Beng Subculture and the Anti-Capital of Social Exclusion. UKM Ethnic Studies Paper Series No. 54 (August). Bangi: Institute of Ethnic Studies. 106 pages. http://www.ukm.my/kita/news/skke54/

[2] Bubak, Oldrich, and Henry Jacek. Trivialization and Public Opinion: Slogans, Substance, and Styles of Thought in the Age of Complexity. Springer, 2019, p. 233.

[3] Martin, Dahlia. “Identity politics and young-adult Malaysian Muslims.” Eras Journal 12, no. 1 (2010): 1-29, p. 10.