by Yvonne Tan

It’s safe to say that words initially created by the Najib administration to identify who would be eligible for aid regardless of social class (like “B40”, “PPR”, “T20”) have officially become part of our everyday lingo, sparking many viral debates about class. In our past blog posts such as The Revolution is Viral and Antara dua Darjat (MCO 3.0 version), we have covered how netizens would call out particular individuals for their tone-deafness, especially during the pandemic. The latest of such individuals included the UiTM lecturer who berated a student for not having a laptop through the immortalized saying “Aku tak boleh duduk orang dengan B40”.

Now it is time to explore the other side of the coin. Recently, the Facebook group B40 Buat Perangai Apa Harini has gained momentum and wide appeal. At the time of writing, the group has amassed more than 27.4k members; it was temporarily paused for 7 days from 26 May to 3 June 2022 with the reasoning from the admin “Group terlalu panas. Bagi sejuk kejap”. The reasoning is most likely due to some of the posts being featured on tabloid outlets, particularly the renovation of a flat to look like a terrace house. The house was described as “Ini B40 kayangan tuan2..pemikiran luar kotak..”

Now it is time to explore the other side of the coin. Recently, the Facebook group B40 Buat Perangai Apa Harini has gained momentum and wide appeal. At the time of writing, the group has amassed more than 27.4k members; it was temporarily paused for 7 days from 26 May to 3 June 2022 with the reasoning from the admin “Group terlalu panas. Bagi sejuk kejap”. The reasoning is most likely due to some of the posts being featured on tabloid outlets, particularly the renovation of a flat to look like a terrace house. The house was described as “Ini B40 kayangan tuan2..pemikiran luar kotak..”

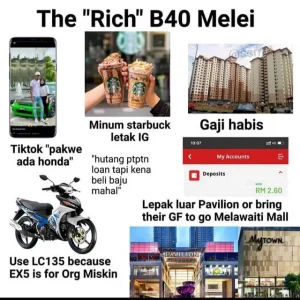

Other posts in the group are not so forgiving, typically featuring a wide range of “things working class people do” that netizens tend to mock or ridicule. From questioning if B40 people truly are suffering and poor – with reference to evidence of fancy, modified Lamborghinis parked at PPR flats – to asserting that B40’s financial troubles stem from having a particular way of thinking that is not smart. Nevertheless, several netizens on the page who are from the B40 group are also self-aware and find what those of the same class group do distasteful.

The phenomenon is too accurately described by the film Parasite (2019) that has helped us articulate class divides during the Central Malaysia floods. Despite being in similar positions, the Kims – an art therapist, chauffeur, and housekeeper of the Park family – recoiled in disgust at Moon-gwang – the previous housekeeper – and refused her plea to help her husband, Geun-sae, remain in hiding in the bunker of the Parks’ house from loan sharks. Having a shared class background and common plight did not mean that they would empathize and share solidarity with one another; rather, the Kims and the couple cling to the possible opportunity for upward mobility with the Parks, which is believed to be reserved to only one family.

The phenomenon is too accurately described by the film Parasite (2019) that has helped us articulate class divides during the Central Malaysia floods. Despite being in similar positions, the Kims – an art therapist, chauffeur, and housekeeper of the Park family – recoiled in disgust at Moon-gwang – the previous housekeeper – and refused her plea to help her husband, Geun-sae, remain in hiding in the bunker of the Parks’ house from loan sharks. Having a shared class background and common plight did not mean that they would empathize and share solidarity with one another; rather, the Kims and the couple cling to the possible opportunity for upward mobility with the Parks, which is believed to be reserved to only one family.

Twitter posts complaining about B40 working habits such as slacking off and foot-dragging have gone viral. In the posts, the attitudes of B40 workers are described to be at odds with those of their M40 manager and T20 boss who are responsible for supervising them. Rationalisations that B40 deserve to be where they are are plentiful, which are typically summed up as “poor people mentality”. This idea that there is a very real possibility of being able to transcend one’s class through simply hard work and switching off “class mentality” is still salient here. In fact, it is at times the defining justification for why some people are in the B40 class. Maybe it’s our own weird version of the American dream, where the poor deserve to be poor, even with the understanding that it is not possible for everyone to achieve wealth due to scarcity of opportunities.

One could argue that working class subcultures like Rempit and Ah Beng have been subsumed under the larger umbrella of expressions used to mock the B40 group. Things like modified cars are immediately labelled as an indicator of someone from B40, which comes as no surprise as their group description explains that it was initially created to “memasyhurkan golongan motor ekzos bising sebagai “B40”. Tapi dikembangkan untuk merangkumi segala aspek perangai B40.” Asset ownership, such as spacious housing or luxury cars, are lifestyle indicators that are key in cementing and signalling middle-class status. [1] Thus, when the B40 group attempts to achieve the same “look” in a much more low-cost manner such as creating a bungalow out of two flats or modifying cars with loud exhausts, instead of “working hard” to accumulate money and transcend one’s class, those attempts are subjected to ridicule.

One could argue that working class subcultures like Rempit and Ah Beng have been subsumed under the larger umbrella of expressions used to mock the B40 group. Things like modified cars are immediately labelled as an indicator of someone from B40, which comes as no surprise as their group description explains that it was initially created to “memasyhurkan golongan motor ekzos bising sebagai “B40”. Tapi dikembangkan untuk merangkumi segala aspek perangai B40.” Asset ownership, such as spacious housing or luxury cars, are lifestyle indicators that are key in cementing and signalling middle-class status. [1] Thus, when the B40 group attempts to achieve the same “look” in a much more low-cost manner such as creating a bungalow out of two flats or modifying cars with loud exhausts, instead of “working hard” to accumulate money and transcend one’s class, those attempts are subjected to ridicule.

Audi Ali in his article Why Is It Difficult to Organise Around Class in Malaysia speaks on our recent status consciousness, which one would think would go hand in hand with class solidarity. He argues that, through the New Economic policies, rapid modernisation had moved the middle class from working in agriculture to working in the service sector. This blurred class relations and obfuscated workers’ disenfranchisement. As terms like B40, M40, and T20 contributed to making class more visible, the fact is that this visibility is still based on income. As Ali argues, the visibility should instead be about “the causal chain between poverty and capitalist exploitation [which] is rarely made explicit in these analyses. Perhaps this failure to reveal how labour is exploited by both the state’s bureaucratic elites and capital has created apathy—if not antagonism—among the middle classes towards the poor.”

In our post-Covid world where class antagonisms have become part of our vocabulary that does not replace, but rather complements our racial stereotyping, where has all the solidarity gone? During Covid, there was a clear disparity between the upper and lower classes with regards to selective prosecutions, but the criticism was not necessarily directed at the systemic failure of our government to ensure that there were no double standards and abuse of power when it came to criminal law. Class stereotypes are forming in the same way we approach race, writing off certain groups on the basis of specific behaviours that are predicated on the principle that these behaviours would be different if these groups had a “better” mindset. The day we realise classifications divide us and lead us into scapegoating one another, is the day we recognise the institutional mechanisms in place that continue to keep those in power.

References

[1] Embong, A., 2002. State-led modernization and the new middle class in Malaysia. Springer, p. 100.