by Dorothy Cheng

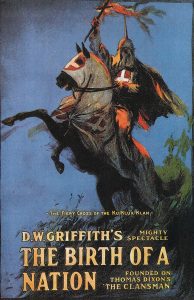

Just a few weeks after its premiere, the 1915 hit film The Birth of a Nation was banned in multiple states across the United States. Throngs of people rioted outside cinemas that screened the film. Public figures made fiery statements decrying its message. The film became a political tool that is still deeply relevant to this day.

So what was all the fuss about?

The turn of the century had come and gone, but the United States was only 50 years freshly removed from the Civil War and at the apex of Jim Crow. The film was about the Southern spirit, with the Ku Klux Klan acting as the protagonist, fighting against authoritarian abolitionists and insidious freed slaves. It was a powder keg of racial tension.

Malaysia almost had our own Birth of a Nation moment. The 2022 film Mat Kilau has been making waves for its purported racial insensitivity. It has been accused of being racist, fascist and historically inaccurate. But there is much more to this conversation. We need to talk about collective trauma, colonial conceptions of race and art as a tool to heal from trauma. We need to talk about Mat Kilau.

The Role of Art in Shaping Society

It is a testament to the influence and artistic merit of Mat Kilau that important conversations are being derived from it. But Mat Kilau is not unique in this sense; art and films have always played central roles as propaganda tools in wider social conditioning projects. At the very least, they are mirrors of the opinions, cultures and conversations that shape a nation or people, especially if the film deals with a historical or political subject.

In 1915, 50 years after the Civil War, the United States was still a divided country (and still is to this day). There was a division between former Union and former secessionist states, between African Americans and whites, between anti- and pro-Jim Crow corners and of course, between those who liked The Birth of a Nation and those who thought it was “the most reprehensibly racist film in Hollywood history”.

A film like The Birth of a Nation is a product of its time. It is a film about Southern white pride and identity in an age that was moving away from the agrarian past and embracing new, progressive values. It is a film about Southern white heroism and victimhood in an age when African Americans were beginning to be recognized as free citizens. It is a film that panders to white superiority and insecurity in a time of change, arresting its audience in a freeze-frame of an escapist narrative so they can relive “better” times.

A film like The Birth of a Nation is a product of its time. It is a film about Southern white pride and identity in an age that was moving away from the agrarian past and embracing new, progressive values. It is a film about Southern white heroism and victimhood in an age when African Americans were beginning to be recognized as free citizens. It is a film that panders to white superiority and insecurity in a time of change, arresting its audience in a freeze-frame of an escapist narrative so they can relive “better” times.

Films do not only show us what is unsaid in society. It also reinforces ideas and can go on to inspire change. In the wake of the film’s premiere, lynchings of African Americans throughout the country spiked and the Ku Klux Klan’s membership boomed.

Malaysia in 2022 is not comparable to America in 1915. But there are similar conditions at play here and to say that Mat Kilau is just a film with no bearing on reality is to not do its narrative effectiveness justice. Stories have power. It is why Mat Kilau was made in the first place, so Malays could look to it as a monument to their history and culture. Stories are especially important for post-colonial societies. Much of the project of nation-building comes down to the ability to form a cohesive identity and to take from a shared history. Without stories, there are no identities.

Mat Kilau as a Post-Colonial Nation-Building Story

We are as far removed now from British colonialism in Malaya as America was from the Civil War at the time of The Birth of a Nation’s premiere. Malaysian Independence was only achieved 65 years ago. There are people alive today who remember the British and their rule over this land, just as in 1915 in America when Civil War veterans and former slaves were still alive. The wounds of colonialism are fresher than we think. We needed a story to serve as a balm.

Throughout Mat Kilau, numerous characters reference the British perception of Malays as a race bogged down by infighting, apathy and a general inability to self-govern and prosper. This is not fictional as there is a wealth of evidence of British attitudes towards Malays, and of course, firsthand testimony from many who lived through British rule.

In his paper “The Making of Race in Colonial Malaya: Political Economy and Racial Ideology“, Charles Hirschman points out that the British treatment of Malays came down to one overarching theme: paternalism. Paternalism, in a colonial context, is the idea that a more superior force must rule over an inferior group due to that group’s inherent lack of capability. Hirschman identifies British stereotypes of Malays as lacking intellectual capabilities and being lazy, in particular.

The British naturalist A. R. Wallace said, ” In intellect the Malay is but mediocre. He is deficient in the energy requisite for the acquisition of knowledge, and seems incapable of following out any but the simplest combinations of ideas.” This is a man who went on to make significant contributions to evolutionary science, so we must not underestimate how deeply-rooted and pervasive racism can be in our canon of knowledge, and how these stereotypes can continue to affect people today.

Of course, there is a much simpler explanation for these supposed attitudes of the Malays that the British conveniently missed. In his book The Myth of the Lazy Native, Syed Hussein Alatas points out that many Malays stood to gain nothing by working for the British, considering it was their land that was being exploited and their profits that were being funnelled overseas. But this stereotype was continually pushed and set the tone for the British subjugation of the Malays. The erasure of Malay accomplishments and emasculation of Malay prowess, combined with the material reality of colonial rule, suppressed Malay cultural pride and economic emancipation.

We do not tend to think of colonialism as a traumatic event the way we rightly think war is. But the truth is that colonial trauma is real, and it is intergenerational. The myth of inferiority and feelings of helplessness and subjugation can be passed down from generation to generation.

We do not tend to think of colonialism as a traumatic event the way we rightly think war is. But the truth is that colonial trauma is real, and it is intergenerational. The myth of inferiority and feelings of helplessness and subjugation can be passed down from generation to generation.

That is why stories like Mat Kilau resonate so much. Malaysia does not have a large library of historical cinema dealing with post-colonial themes. China has Ip Man. India has Gandhi. Why shouldn’t Malaysia also have stories that undo the erasure of Malay accomplishments and correct the myths about the Malay race and culture? Without stories to uplift a nation, dominant narratives will take center-fold. Malaysians must replace outsider narratives with our own.

But did Mat Kilau achieve this?

Mat Kilau as a Continuation of Colonial Racial Narratives

One of the key things the movie forgets is that this colonial trauma is shared. The idea of inferiority, medicated by the unyielding force of colonial paternalism, is one that plagued all communities in Malaysia today. The great civilizations of China and India were brought to their knees before Western powers. That trauma followed Chinese and Indian immigrants to Malaya. Then, as colonial subjects in Malaya, the Chinese and Indians also became victim to stereotyping and racism as part of the British “divide and conquer” strategy, but also in the service of the wider Western curiosity surrounding scientific racism.

With its caricatures of Chinese merchants and Sikh soldiers, Mat Kilau adopts the very race rhetoric that the British used in Malaya but conveniently excludes Malays from it. Therefore, instead of presenting a Malaysian post-colonial narrative, it simply repurposes the colonial racial narrative for its own use.

Frank Swettenham wrote of the Chinese: “It is almost hopeless to expect to make friends with a Chinaman. And it is, for the Government Officer, an object that is not very desirable to obtain. The Chinese, at least that class of them met with in Malaya, do not understand being treated as equals.” According to Hirschman, he and other British contemporaries primarily defined the Chinese as having no morals above greed, and as such, developed resentment and distrust of them.

At once contemptuous of Indians but reliant on them for the massive amounts of labour required for their absurdly international conquests, the British invented a convenient stereotype for specific Indian communities, including the Sikhs: the concept of a “Martial Race.” According to the historian Jeffrey Greenhunt, “The Martial Race theory had an elegant symmetry. Indians who were intelligent and educated were defined as cowards, while those defined as brave were uneducated and backward.” The wider aim of this British narrative within India was to divide different Indian communities by pitting “loyal” ones against ones that were “disloyal” and that had rebelled and mutinied against the British.

Mat Kilau’s narrative recognizes the incorrectness of the British stereotype against Malays while entirely leaning into similar stereotypes the British made about the Chinese and Sikhs. The Chinese character Goh Hui is a greedy, scheming and slimy character who doesn’t do anything if it does not benefit him personally, and the Sikh soldiers are violent, cruel and wholly obedient to their British masters.

Mat Kilau’s narrative recognizes the incorrectness of the British stereotype against Malays while entirely leaning into similar stereotypes the British made about the Chinese and Sikhs. The Chinese character Goh Hui is a greedy, scheming and slimy character who doesn’t do anything if it does not benefit him personally, and the Sikh soldiers are violent, cruel and wholly obedient to their British masters.

Worse still, these racial tensions between the Malays and the non-Malays culminate in violence against Goh Hui and numerous Sikh soldiers, but not a single drop of British blood was spilled. Are the Chinese and Sikh characters merely obstacles in the Malay fight for justice? Are they simply a box to be checked before Mat Kilau and gang can defeat the final boss in the inevitable sequel? Are the British simply long-forgotten as a historical relic and therefore, not even worthy of an end, while the Chinese and Indians are the real threats that exist today? The symbolic violence of killing the only Chinese character with dialogue and of scene after scene of corpses dressed as Sikhs surely is not something a Malaysian Chinese or Sikh person can sit through without feeling like there is a message being directed at them.

Mat Kilau has its Chinese and Sikh characters spout mantras about British superiority, professing their undying loyalty to the very people who crippled their motherlands. This choice to erase Chinese and Indian colonial trauma is an interesting one. Was it an indictment of Chinese and Indian loyalty to Malaysia? Was it a moral message about uniting as a nation of Malaysians, regardless of race?

As a Malaysian Chinese person, I came out of my viewing of Mat Kilau reflecting on whether or not non-Malays are truly uninterested in the larger project of helping Malaysia prosper, or whether continued racial tensions, coupled with the inherited racial stereotypes from the British, have created a collective memory among some Malays that non-Malays are not to be trusted.

That begs the question: do the narratives of race in Mat Kilau simply reflect a reality of how non-Malays are perceived in this country?

Beyond Mat Kilau: Future Malaysian Post-Colonial Narratives

Collective trauma and collective memory go hand in hand: the Malay experience of British colonialism was of having their lands taken from them, their ambitions quelled, their kings weakened and their society and ways of living fundamentally changing. Their collective memory was of the arrival of foreigners in a time of change and how these foreigners all behaved in certain ways that largely coincided with the disenfranchisement of the Malays.

Like The Birth of A Nation, Mat Kilau is about addressing the anxieties of a particular race, arresting a moment in history for them to place themselves in so they can relive a better time.

Art heals trauma. The first step is to talk about it. It is crucial to note that Mat Kilau is only one retelling of the Malay experience, which is not universal. Whether we agree with this manifestation of collective memory about non-Malays is irrelevant, because we cannot begin to address that if we do not first understand it.

I only hope that Malaysian Chinese and Malaysian Indians will have the same opportunities to convey what our trauma looks like. When that time comes, will Malaysians still say “It’s just a movie, don’t be so sensitive?”

Ultimately, the goal should be to get to a place where we can tell stories that reflect the true diversity of a Malaysian narrative. Until then, siloed messaging is a baby step that young, post-colonial countries live with until we feel like we’ve aired out all our trauma – Malays have always made movies for Malays, Chinese for Chinese and Indians for Indians. Of course, there are exceptions, and I would never propose foregoing the telling of individual communities’ stories in favour of some contrived muhibbah narrative.

Ultimately, the goal should be to get to a place where we can tell stories that reflect the true diversity of a Malaysian narrative. Until then, siloed messaging is a baby step that young, post-colonial countries live with until we feel like we’ve aired out all our trauma – Malays have always made movies for Malays, Chinese for Chinese and Indians for Indians. Of course, there are exceptions, and I would never propose foregoing the telling of individual communities’ stories in favour of some contrived muhibbah narrative.

The Birth of a Nation was banned. I don’t think Mat Kilau should be. As a movie, it is a watershed moment for Malaysian cinema and its technical capabilities. It is also an important piece of a larger conversation we need to be having in our society. What can we all do to forge our own narratives? What would a film about the Malaysian anti-colonial struggle across cultures, religions and races look like? What would a Malaysian film that touches on racial tensions look like if it were created with the input of all the affected races? I do not want to tell people to forcibly change their collective memory, nor do I think it is possible in a short amount of time. But I do think we need to keep telling our stories to each other. Tell me your memories and I’ll tell you mine, and somewhere along the way, we can heal.