by Yvonne Tan

Think of an indigenous martial art in Malaysia. Immediately we would think of silat. However, like most places in Southeast Asia, each place has a variant of Muay Thai. Myanmar has Lethwei, which is usually said to be one of the more brutal martial arts around given it permits headbutting and is usually done bare-knuckle, traditionally operating by knockout only to win. Cambodia’s Pradal Serey or Kun Khmer is known for its higher frequency of elbow strikes while Laos’ Muay Lao has a lack of it. In 1995 Cambodia wished to unite the ASEAN martial arts under “Sovannaphum boxing” or “SEA boxing” representing Thailand, Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar, however, the nations were not keen on this, wishing to preserve their own unique form.

Although there is general agreement these forms originate from Muay Boran, a descendant of the traditional martial art Musti-yuddha, most of these variants have been eclipsed by the rise of Muay Thai. Musti-yuddha comes from Sanskrit literally meaning “fist fighting” or “fist combat” which had some of its earliest references from classical epics such as Ramayana, Mahabharata, Rig Veda and Gurbilas Shemi.

The Malaysian variant, Tomoi, which is mostly practised in the northern states, had reached peaked popularity in the 1970s and 80s before being banned in 1990 alongside Mak Yong and Wayang Kulit for its Hindu-Buddhist influences. Hence, many Malaysians now simply refer to the art as Muay Thai or kickboxing to distance the art from being a localized sport and instead paint it as a neutral, international sport originating from Thailand. Thus, the Tomoi-specific rules and rituals before the ban are hardly popularized in comparison.

The Malaysian variant, Tomoi, which is mostly practised in the northern states, had reached peaked popularity in the 1970s and 80s before being banned in 1990 alongside Mak Yong and Wayang Kulit for its Hindu-Buddhist influences. Hence, many Malaysians now simply refer to the art as Muay Thai or kickboxing to distance the art from being a localized sport and instead paint it as a neutral, international sport originating from Thailand. Thus, the Tomoi-specific rules and rituals before the ban are hardly popularized in comparison.

If you have ever watched a Muay Thai match, immediately you would recognize the Sarama music played alongside the pace of the match and the audience, an apparent feature differing from western boxing. Typically performed by four musicians, playing a Javanese oboe (pii chawaa), a pair of lace drums (klong khaek) and brass cupped symbols (ching chap). They are sometimes swapped with the serunai and the gendang in Tomoi matches. The music begins all the way from the Wai khru ram muay ritual, roughly translated as “war-dance showing respect to the teacher”, which is carried out before the match in Muay Thai competitions.

The dance not only gives salutations to Buddha, Dharma, and the sangha of monks but also to their teachers and the spirit of the ring. It also provides clues to the fighter’s style and abilities which has relevance for betting as well. Many of the Ram Muay dances are influenced by Hanuman from the epic Ramayana and chanting alongside the dance is common. Southern Thailand boxers instead ask for protection from Allah before starting or skip through the salutations. Namsaknoi Yudthagarngamtorn is one of the better-known Muslim boxers in the Muay Thai world who was awarded the best Wai Kru Ram Muay of the year twice, in 2001 and 2006 (Although Thailand itself is far from an example for being accommodative to other religions).

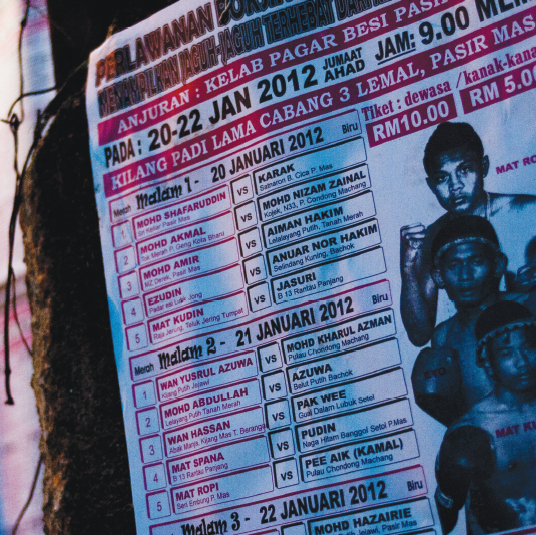

However, with Tomoi, after the ban was lifted in 2006 matches now must be sanctioned by the Kelantan Boxing Association (KBA) led by Ramli Awang and the Kelantan police. The ritual is now replaced with Quranic prayers recitals and chanting is deemed illegal. Fighters also must produce a daily logbook of their training regiments through a manager and the winner is adjudged by a technical knockout (TKO) points system. No betting was allowed as well. Tomoi was also allowed to be practised under the proposed name of “Muay Kelate” but as mentioned earlier kickboxing or Muay Thai is preferred.

However, with Tomoi, after the ban was lifted in 2006 matches now must be sanctioned by the Kelantan Boxing Association (KBA) led by Ramli Awang and the Kelantan police. The ritual is now replaced with Quranic prayers recitals and chanting is deemed illegal. Fighters also must produce a daily logbook of their training regiments through a manager and the winner is adjudged by a technical knockout (TKO) points system. No betting was allowed as well. Tomoi was also allowed to be practised under the proposed name of “Muay Kelate” but as mentioned earlier kickboxing or Muay Thai is preferred.

Why are we able to welcome with open arms the combat sport when it is branded as a foreign product that comes with globalization, and have the opposite reaction when the sport is one’s own culture? Asking as Homi K. Bhaba does: “in what sense, then, does a nation-centred discourse create an immobile curricular perspective?” [1]

Looking at the national martial art in Malaysia, silat, itself also has roots in Hindu-Buddhism and animism from its folkloric origins to the images of Hindu figures on weaponry. Although it is also illegal for Muslim practitioners to carry out incantations and meditation, the martial art is effectively decided and celebrated as “local” and “indigenous”. As silat is popularly tied to the 15th century Malacca Sultanate, arguably the most important narrative for Malay Muslim civilization, making appearances in Hikayat Inderajaya and Hikayat Hang Tuah. Silat continues to be featured semi-regularly in box office films such as Malaysia’s first colour film Hang Tuah (1956) and its first big-budget film Puteri Gunung Ledang (2004).

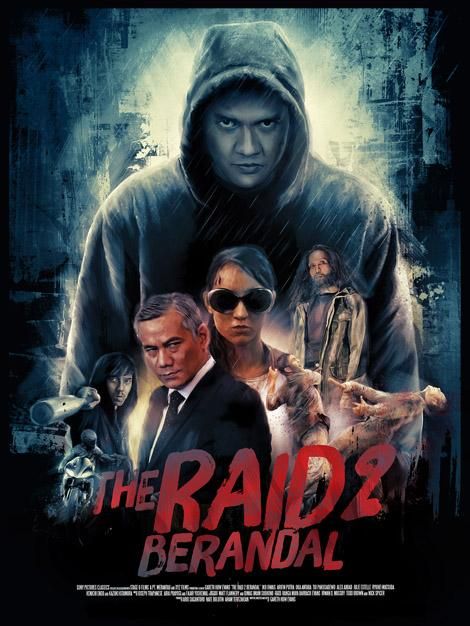

Nevertheless, not all portrayal of silat was celebrated. Take, for instance, silat in the internationally acclaimed movie The Raid: Redemption (2011) sequel, The Raid 2: Berandal (2014) was banned from screening for its “excessive violence”. Hence, a specific representation of silat is “prioritize[d] [by] linguistic authenticity, affirming cultural supremacy, and making claims to historical continuity and political progress. These shared discourses of national legitimation are articulated in affective structures of belonging that feel invariably “local” despite their hybrid, international, or intercultural genealogies.” [1]

Nevertheless, not all portrayal of silat was celebrated. Take, for instance, silat in the internationally acclaimed movie The Raid: Redemption (2011) sequel, The Raid 2: Berandal (2014) was banned from screening for its “excessive violence”. Hence, a specific representation of silat is “prioritize[d] [by] linguistic authenticity, affirming cultural supremacy, and making claims to historical continuity and political progress. These shared discourses of national legitimation are articulated in affective structures of belonging that feel invariably “local” despite their hybrid, international, or intercultural genealogies.” [1]

With silat chosen to represent the epitome of Malay Muslim masculinity, Tomoi has been neutralized of its local ties with emphasis on its Hindu-Buddhist elements of a foreign country despite both sports originating from a melding of various cultures. Repeated calls to lift the ban on Mak Yong and Wayang Kulit, did not necessarily include Tomoi as it was seen as a violent sport operating also as gambling dens with regular ruckus among the audience much like cock-fighting. If modern silat represents refinement and continuation of cultural values, Tomoi is the opposite. Gaik Cheng Khoo coined the term “silat masculinity”:

He represents the average-looking Malay Everyman: clearly not of Eurasian descent, he sports a moustache, has a toned and lean body that is a product of traditional silat rather than the gym and steroids. However, such authenticity necessitates performativity and thus, the traditional hero accessorizes himself with a phallic-shaped weapon such as a keris or badik (both are traditional daggers considered to have magical proper ties) or a gun, which he has to be prepared to use to defend traditional Malay values (and/or femininity)” [2]

In contrast, the critically acclaimed film Bunohan (2011), Tomoi is central to the plot, Adil who is a “kickboxer” that has fallen deep into debt and his father Pok Eng who was a renowned wayang kulit practitioner now struggling to make ends meet with the ban on the craft. Set in a border town of Kelantan, the middle brother Bakar comes back from Kuala Lumpur hoping to sell his family’s land to a large corporation looking to develop it into a resort and in one of the final scenes of the movie Pok Eng confronts Bakar in Kelantan Malay, “you’re so crude, all you care about is land”. Besides the un-Islamic elements, Tomoi is seen as a rural cultural practice as with many others that should be left behind with the lack of space to operate under PAS’ moral and spiritual rectitude and UMNO’s economic growth and development driven narrative. Reaching urban centres as Muay Thai, devoid of its long local history, there is still an immense potential to reclaim the martial art’s roots back within these neutralized spaces, but one can only guess the trajectory of Tomoi’s continuity or lack thereof.

In contrast, the critically acclaimed film Bunohan (2011), Tomoi is central to the plot, Adil who is a “kickboxer” that has fallen deep into debt and his father Pok Eng who was a renowned wayang kulit practitioner now struggling to make ends meet with the ban on the craft. Set in a border town of Kelantan, the middle brother Bakar comes back from Kuala Lumpur hoping to sell his family’s land to a large corporation looking to develop it into a resort and in one of the final scenes of the movie Pok Eng confronts Bakar in Kelantan Malay, “you’re so crude, all you care about is land”. Besides the un-Islamic elements, Tomoi is seen as a rural cultural practice as with many others that should be left behind with the lack of space to operate under PAS’ moral and spiritual rectitude and UMNO’s economic growth and development driven narrative. Reaching urban centres as Muay Thai, devoid of its long local history, there is still an immense potential to reclaim the martial art’s roots back within these neutralized spaces, but one can only guess the trajectory of Tomoi’s continuity or lack thereof.

[1] Bhabha, Homi K and Sorensen, Diana (eds.) Territories and Trajectories: Cultures in Circulation. Duke University Press, 2018, p. 2.

[2] Khoo, Gaik Cheng. “Gendering Old and New Malay through Malaysian auteur filmmaker U-Wei Haji Saari’s literary adaptations, “The Arsonist” (1995) and “Swing My Swing High, My Darling” (2004).” South East Asia Research 18, no. 2 (2010): 301-324, p. 315.