by Yvonne Tan

Whoever you thought was an untouchable celebrity, people have now decided they are not.

As the COVID-19 pandemic carries on and livelihoods are on the deep end, more than ever people are enraged at the class divides that determine how unaffected one can be from the pandemic. This phenomenon is of course a global one. Kim Kardashian was told to “read the room” when she posted her surprise birthday trip for the whole family to a private island. Meanwhile half of Hollywood has moved to Australia, earning the nickname “Aussiewood” and enraging the nation for the double standard as many Australians remain stranded overseas since its borders were closed.

Ahmad Fuad Rahmat argued “the class war” outrage against Vivy Yusof and Ashraf Ariff was now populist. The former reacted with a series of defamation lawsuits against netizens who “allegedly slandering her on the issue of the government helping the B40 and M40 groups affected by the Covid-19 outbreak”. She continued to make social media headlines afterwards for plagiarism issues from multiple local designers and threatened legal action against some. Soon after, Vivy Yusof doubles down on COVID-19 donations and Fashion Valet celebrates its 10th anniversary.

Neelofa dan suami mengaku tidak bersalah di Mahkamah Majistret di sini atas kesalahan melanggar SOP PKPB.

— fotoBERNAMA (2021) HAK CIPTA TERPELIHARA

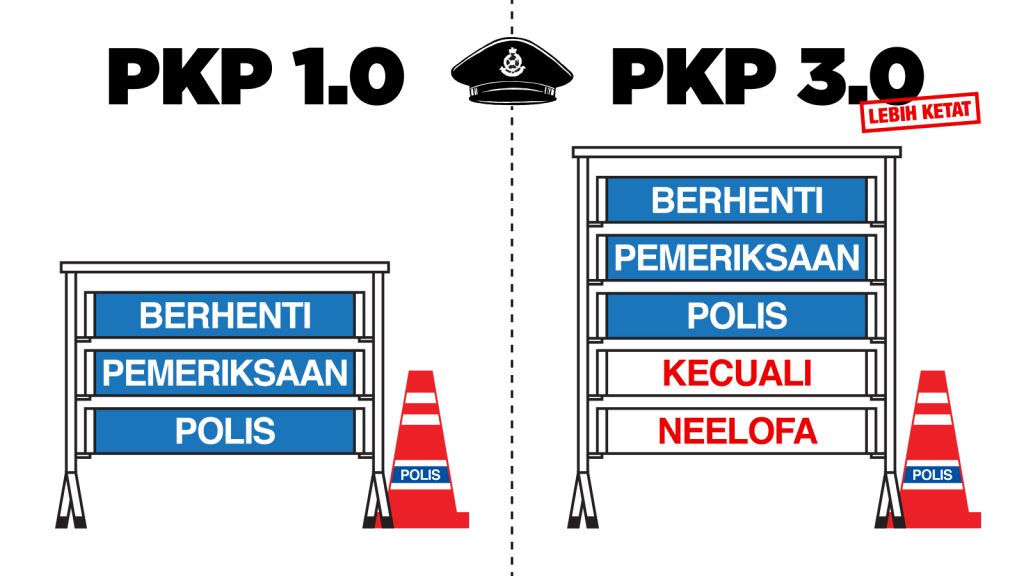

By now, Neelofa’s wedding and Siti Nurhaliza’s son’s tahnik ceremony has been viral for the wrong reasons. Farah Nabilah and Neelofa’s honeymoon was met with intense backlash. Come Raya where many lamented they had already made preparations only to be told MCO 3.0 would be in effect. Outrage against ministers ensued and Neelofa was once again trending on Twitter for her consistent violation of SOP even in court. Norman Hakim, famous for his police role in Gerak Khas, came under fire as well for similar Hari Raya Aidilfitri family photos.

George Packer’s op-ed “Celebrating Inequality” situates modern celebrities through the lens of class. He argues that the modern American celebrity that was once the illusive, illicit “Great Gatsby” of the roaring twenties has been transformed into “self-invented” celebrities that commodify their persona that is associated with the consuming class:

The celebrity monuments of our age have grown so huge that they dwarf the aspirations of ordinary people, who are asked to yield their dreams to the gods: to flash their favourite singer’s corporate logo at concerts, to pour open their lives (and data) on Facebook, to adopt Apple as a lifestyle. We know our stars aren’t inviting us to think we can be just like them. Their success is based on leaving the rest of us behind [1].

Although Packer exclusively looked at America, Neelofa fits the bill. Far from her days on MeleTOP, today she is an Instagram influencer representing modest fashion which led to the creation of Naelofar Hijab and The Noor, marketing exclusively religious products for her ever-growing empire. Her choice to don the niqab and remove previous photos where she did not do so, her marriage to preacher PU Riz makes her the epitome of a celebrity anchored to an essential class identity in the B40 and M40. One could argue that it is the reason for her mass appeal especially when celebrity culture is typically associated with the erosion of traditional values. We are called to adopt a more religious lifestyle together with her products, but leaves us behind as her sponsored posts feature Swarvoski, Gucci and other luxury brands.

Azwan Ali became a fierce critic of Neelofa and other celebrities in this viral video filmed at Bangsar Village. In the interview, he spoke a mishmash of things from asserting his right to speak as “hak rakyat kita sebagai orang Malaysia”, his knowledge of the law and that people should not fear to voice out their opinion. However, he offhandedly mentioned that the government is not to be blamed and that the law should be followed. I am inclined to believe Azwan Ali’s sentiment represents the outrage towards celebrities.

Amid social media calls for brands to boycott Neelofa, like Vivy Yusof before, with many petitions floating around the internet, there is a sense of participation that is central to celebrity culture. People are being sorely reminded that despite the clear double standard on display, class divides remain pervasive but there is still a clear belief that the law should be upheld, and people like Neelofa should be treated the same as everyone, rather than an overhaul of the system.

“Celebrity is a form of improvisatory, excessive public theatre. It is class pantomime” [2] where participation whether in support or in humiliation is central to celebrity culture. Some would argue that people derive entertainment from engaging even virtually via boycott campaigns, petitions, social media hashtagging and so on. Discontent is growing and only time will tell if it expands into a sustained critique of our penal institutions as for now it remains targeted to specific high-profile individuals who were once held in high regard in Malay pop culture.

During the ongoing outrage directed against Neelofa, a small tide turned a little into questioning the police on a separate matter. In stark contrast within the span of almost a month, there have been two deaths in police custody at Gombak district police headquarters (IPD). Security guard Sivabalan Subramaniam died within an hour in police custody while cow milk trader A. Ganapathy succumbed to his injuries caused by police brutality after spending over a month at the Selayang Hospital’s intensive care unit. The Gombak police chief has openly threatened the general public for questioning the events leading up to Ganapathy’s death and made an example by investigating Syed Saddiq’s TikTok video under Section 503 of the Penal Code and Section 233 of the Communications and Multimedia Act.

During the ongoing outrage directed against Neelofa, a small tide turned a little into questioning the police on a separate matter. In stark contrast within the span of almost a month, there have been two deaths in police custody at Gombak district police headquarters (IPD). Security guard Sivabalan Subramaniam died within an hour in police custody while cow milk trader A. Ganapathy succumbed to his injuries caused by police brutality after spending over a month at the Selayang Hospital’s intensive care unit. The Gombak police chief has openly threatened the general public for questioning the events leading up to Ganapathy’s death and made an example by investigating Syed Saddiq’s TikTok video under Section 503 of the Penal Code and Section 233 of the Communications and Multimedia Act.

Some groups have called to bring back the Independent Police Complaints and Misconduct Commission (IPCMC) Bill 2019. As #JusticeForGanapathy and #BrutalityinMalaysia trends alongside #Neelofa in Malaysia, the two ends of the Malaysian social media have yet to be placed side by side as a clear representation of the deep class divides that plague Malaysia. Unlike Neelofa who is caught in a media storm, Ganapathy and Subramaniam were on the receiving end of disciplinary power exercised through its invisibility.

References

[1] Packer, G. 19 May 2013. ‘Celebrating Inequality’ The New York Times [https://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/20/opinion/inequality-and-the-modern-culture-of-celebrity.html]

[2] Tyler, I. and Bennett, B., 2010. ‘Celebrity chav’: Fame, femininity and social class. European journal of cultural studies, 13(3), pp.375-393, p. 380.