by Yvonne Tan

Some of us grew up with cop films—either local or international—that portray a life of action and excitement hunting down bad guys and saving the world. Some of these films were jam-packed with action and martial arts while others exuded sex appeal. Maybe some of us grew up with stories of a lone, amateur detective like Sherlock Holmes, who makes up for the uselessness of the police force. However, our real experiences with cops tend to be completely different. Bureaucracy makes up a huge part of police work and the police vs. villains dichotomy does not seem as clear-cut.

Prisons and the police may seem like background government agencies that many of us hardly encounter, besides the occasional bribe typically dealing with driving rules. Or maybe if there is something seditious on social media, you may quickly encounter the hashtag #PDRM in the comments.

Prisons and the police may seem like background government agencies that many of us hardly encounter, besides the occasional bribe typically dealing with driving rules. Or maybe if there is something seditious on social media, you may quickly encounter the hashtag #PDRM in the comments.

But to others, the police force is a lot more prominent. One time, my friends and I got into a car and one immediately said: “Luckily we have one Chinese girl here, if not we will be stopped by the police”. Another time, we were actually stopped by the police and asked to hand over our MyKads, with torchlights flashed into our faces before being let go. A friend commented again that we were only let go because of me.

This stop-and-search process is probably the reality of many Malaysians and people living in Malaysia, especially with tightened pandemic restrictions. Many people often think about what we would have to do if we were “unlucky” enough to be stopped by the police. Solutions include calling in favours, trying to offer larger bribes and finding different ways to ensure they don’t get beat up. Probably the most famous instance of Malaysian police violence was Anwar Ibrahim’s black eye, and things have not changed since.

SUARAM reported a total of 456 deaths in police custody in the year 2020, including prisons and immigration centres. This year, there was a significant public outcry over the custodial deaths of A. Ganapathy, a cow milk trader, S. Sivabalan and a security guard, who died a mere hour after his arrest. But the custodial deaths did not stop and threats to the public were made. People were threatened for commenting on the issue and an example was made of Syed Saddiq. You can’t make this up.

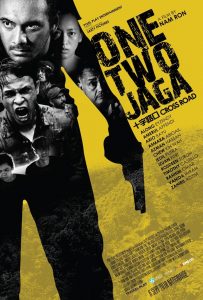

One Two Jaga is one of the few films in Malaysia that placed corruption at the center of its subject, with story arcs of how poor wages in the police force led to corruption. The film critiqued the optimism of the police vs. villains dichotomy.

One Two Jaga is one of the few films in Malaysia that placed corruption at the center of its subject, with story arcs of how poor wages in the police force led to corruption. The film critiqued the optimism of the police vs. villains dichotomy.

The people who have suffered most at the hands of the police are migrant workers. There is a clear understanding that not only do you have to be the right colour but also be socioeconomically well-off in order to keep the police off your tails. Our police force works the way it does because of our racism to others. Many Malaysians still believe that victims of the police deserve it, falling back on racial stereotypes as justification. The “logic” of illegal migrant workers and the Indian community’s supposed high tendency for crime has made it easy to dismiss police brutality because these people simply “deserve” it for breaking the law.

Rarely do we ever see them as victims of circumstance. They are instead seen as a social threat and exaggerated racial differences provide legitimacy to our criminal justice system. The police tend to be seen as operating in a faultless mechanism. If there are indeed faults, they would be blamed on maybe a few rotten eggs. This allows for the continuous justification of excessive police harassment and force. The truth is, the police force is an institution which can have competing interests against ours, and minorities are especially socially disadvantaged.

Take for example Malaysia’s remand system, which allows the police to apply to the Magistrate to detain anybody for longer than 24 hours for further investigation. The Magistrate can also order the police to do the same. After 24 hours, your detention period can be extended up to 14 days. At the end of the detention period, the police should release you or bring you before the Court to be charged. In theory, your relatives and lawyer should have details of your arrest and remand. However, chain remand has been a common practice, allowing for detention without trial under the Security Offences (Special Measures) Act 2021 (SOSMA) and POCA despite no charges being brought against a person.

Take for example Malaysia’s remand system, which allows the police to apply to the Magistrate to detain anybody for longer than 24 hours for further investigation. The Magistrate can also order the police to do the same. After 24 hours, your detention period can be extended up to 14 days. At the end of the detention period, the police should release you or bring you before the Court to be charged. In theory, your relatives and lawyer should have details of your arrest and remand. However, chain remand has been a common practice, allowing for detention without trial under the Security Offences (Special Measures) Act 2021 (SOSMA) and POCA despite no charges being brought against a person.

The social aspects of the issue are further worsened by ministers attributing social ills to migrants. For instance, migrants were blamed for spreading Covid-19 due to “poor hygiene” and were even painted as looters during the floods, despite many of them playing an active part in rescuing locals.

Crime is often used as a way for us to air our racial and class biases. The talking points and dog-whistles parroted by political elites who posture as “law and order” allow for such sentiments to become systemic. The official designation and criminalization of PATI (the term used to denote illegal migrants) and the introduction of the word K*ling into the Dewan Bahasa are just two examples of this.

There have been proposals to “prevent corruption” by making police wear bodycams or forming independent bodies to oversee the PDRM. These initiatives have been put under the purview of the Home Ministry. However, we need to challenge the root cause of the issue: the rationalisation that people deserve to have violence enacted on them in the name of crime control. Malaysia’s police violence is rooted in the racial and class prejudice that permeates not only our political systems but also our criminal justice system.