by Yvonne Tan

The future of work is full of precariats. What is a precariat? It is a portmanteau of the words “precarious” and “proletariat”. Terms like “precariat” have taken on more importance with the popularity of the “gig economy”. Back in 2021, NASDAQ listed Grab Holdings Ltd, a Singapore-headquartered company. Some celebrated this, while others lamented the “brain drain” of Malaysian talent. Squabbles like these overshadow a bigger issue: Grab food drivers hardly earn more than RM 5 per trip. They work an average of 12 hours a day only to get RM 2,200 a month.

The future of work is full of precariats. What is a precariat? It is a portmanteau of the words “precarious” and “proletariat”. Terms like “precariat” have taken on more importance with the popularity of the “gig economy”. Back in 2021, NASDAQ listed Grab Holdings Ltd, a Singapore-headquartered company. Some celebrated this, while others lamented the “brain drain” of Malaysian talent. Squabbles like these overshadow a bigger issue: Grab food drivers hardly earn more than RM 5 per trip. They work an average of 12 hours a day only to get RM 2,200 a month.

The story of entrepreneurship has long overshadowed the story of the unfair labour conditions these entrepreneurs’ workers face. Proponents of the gig economy regularly rehash a number of justifications for why labour conditions do not need to be improved. These include supposedly competitive pay, job flexibility and flexible hours.

However, massive strikes and protests led by workers of the gig economy in surrounding countries such as Hong Kong, Vietnam, Indonesia and Thailand have resulted in high-level mediations and changes in government labour policies. These movements were able to achieve this despite most workers never meeting or working with one another. They were able to enact spontaneous collective action while remaining leaderless.

Couriers for GoKilat, Gojek’s GoSend same-day delivery service, recently carried out back-to-back strikes to protest GoKilat’s new incentive scheme. The scheme proposed that couriers who once received IDR 10,000 (US$0.70) for five completed deliveries would now only receive IDR 5,000 (US$0.35).

Couriers for GoKilat, Gojek’s GoSend same-day delivery service, recently carried out back-to-back strikes to protest GoKilat’s new incentive scheme. The scheme proposed that couriers who once received IDR 10,000 (US$0.70) for five completed deliveries would now only receive IDR 5,000 (US$0.35).

After the estimated 100,000 drivers went on strike for three days, Lalamove couriers and Grab drivers also took up the cause, shining a light onto working conditions in Indonesia’s gig economy. These were not isolated cases. Protests and strikes against job suspensions, income reductions and demands for better health insurance have been carried out throughout Indonesia since 2015.

In Hong Kong, it all started with a Foodpanda delivery driver of South Asian descent. He had his account suddenly suspended and expressed his anger in an anonymous group chat of other drivers. The invite link quickly spread and has led to almost 1,500 members today. Now, these drivers were able to share their grievances on exploitative working conditions, racism and low wages. They could organise themselves to go on strike and formed links with local non-profits such as “Concern Group for Food Couriers’ Rights”. They even famously linked up with Boxson, a YouTuber who shares his life as a delivery driver. By November 18, negotiations between strike leaders, who were mostly South Asian workers, and Foodpanda management led to the fulfillment of some of the strike’s 15 demands.

Delivery services have taken on more importance during the COVID-19 pandemic. On top of that, many workers also notably lent a hand in rescue efforts during the flash floods in Malaysia. They are now widely seen as “heroes”.

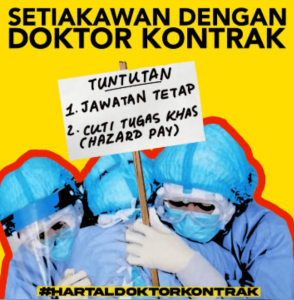

Another group of Malaysian heroes, medical staff, went on strike in July 2021. The Hartal Doktor Kontrak protest called into question the contract system, which said medical officers were not going to be absorbed as permanent staff after five years of service. Many Malaysians had a far more positive reaction to the doctor’s strike than they had to strikes by low-wage workers.

For instance, the J&T strikes in February 2021 were met with anger against the workers for apparently destroying customer packages and not delivering packages on time. The protest against J&T’s change in the commission system, which would reduce the wages for delivery workers, was largely overshadowed by netizens’ anger against worker attitudes. The media also began to spotlight how customers can make complaints against J&T to get their money back, rather than talk about the strike itself. Clearly, we do not treat all our “heroes” equally.

For instance, the J&T strikes in February 2021 were met with anger against the workers for apparently destroying customer packages and not delivering packages on time. The protest against J&T’s change in the commission system, which would reduce the wages for delivery workers, was largely overshadowed by netizens’ anger against worker attitudes. The media also began to spotlight how customers can make complaints against J&T to get their money back, rather than talk about the strike itself. Clearly, we do not treat all our “heroes” equally.

This is in stark contrast with an almost similar experience taking place in April 2021. An innocent chat between a Shopee Express courier and a customer revealed that the reason the package was late was that there were strikes. Shopee was going to cut the pay for each delivered package from IDR 2,000 (USD 0.14) to IDR 1,500 (USD 0.10). Screenshots of the conversation went viral, leading many Indonesian netizens to join the strike online with the hashtag #ShopeeTindasKurir. The online element of the strike was a great platform for Shopee couriers to share stories of their working conditions—stories that are hardly reported or known.

Meanwhile, in Thailand, a mass boycott of Foodpanda under the hashtag #BanFoodPanda was underway. The delivery service had stated that they would terminate an employee for attending an anti-government protest. The boycott was so effective that Foodpanda allegedly lost almost 2 million users and 90,000 merchants. Although, Foodpanda has claimed the numbers were inflated.

Strikes work, even in this region, even without unions. However, public support is a key element in ensuring the success of strikes. The public must want to better working conditions for gig workers. Workers can then use this solidarity as a bargaining tool. Thai, Hong Kong and Indonesian public support for strikes, as well as Malaysian support for Hartal Doktor Kontrak, illustrates this. The Hartal Doktor Kontrak strike resulted in parliament urgently debating the issue despite threats from directors of hospitals and state health departments on medical workers. At the time of writing, the Ministry of Health has promised that contracted doctors will be able to apply for specialist training under Hadiah Latihan Persekutuan.

Strikes work, even in this region, even without unions. However, public support is a key element in ensuring the success of strikes. The public must want to better working conditions for gig workers. Workers can then use this solidarity as a bargaining tool. Thai, Hong Kong and Indonesian public support for strikes, as well as Malaysian support for Hartal Doktor Kontrak, illustrates this. The Hartal Doktor Kontrak strike resulted in parliament urgently debating the issue despite threats from directors of hospitals and state health departments on medical workers. At the time of writing, the Ministry of Health has promised that contracted doctors will be able to apply for specialist training under Hadiah Latihan Persekutuan.

Pundits and economists typically tout gig workers as the future of work. What about the future of demanding better working conditions? Workers should be able to organise in a decentralised and spontaneous manner even in the private sector. Critiquing elitist privilege must come hand in hand with uplifting lower classes. We must recognise that the problem is systematic economic insecurity.

Former Paralympic athlete Koh Lee Peng made headlines for selling tissue packets. She had been unable to secure jobs due to her disability. She mentioned that locals assumed she was part of a syndicate or that she was an illegal foreigner.

Former Paralympic athlete Koh Lee Peng made headlines for selling tissue packets. She had been unable to secure jobs due to her disability. She mentioned that locals assumed she was part of a syndicate or that she was an illegal foreigner.

There is a deep classism against low-wage workers in Malaysia that needs to be addressed. Many locals associate low-wage workers with Southeast Asian or South Asian “foreigners”. The coinage of the term B40, to denote the lowest economic class, brings with it a fair share of critique against the upper-class T20. However, we do not use the term B40 in a way that invokes solidarity. There needs to be more advocacy for inter-class cooperation for the right to fair working conditions.