by Low Tse Yenn

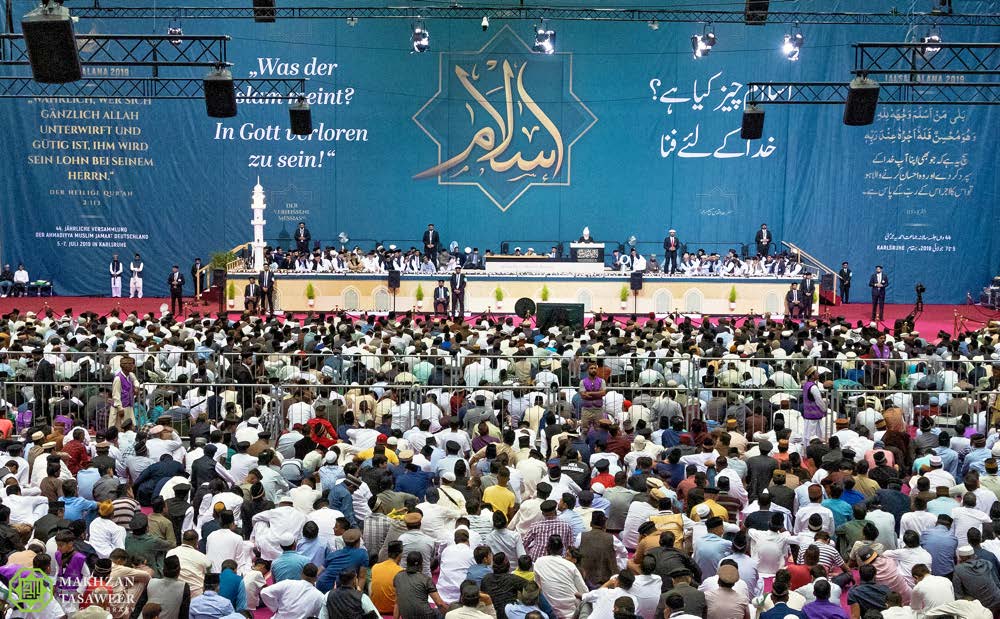

Every year, Ahmadiyya Muslims around the world await the Jalsa Salana – a formal annual religious convention, which allows attendees and spectators alike to explore and expand upon their faith. The convection spans across 3 days, always beginning on a Friday after Friday prayers and coming to a close on a Sunday. While many countries often host their own national Jalsa, the Jalsa Salana UK is an international spectacle – drawing the eyes from Ahmadiyya Muslims worldwide as it is broadcasted on Muslim Television Ahmadiyya (MTA).

The Ahmadiyya Muslim community, who otherwise refer to themselves as the Jama’at, refers to the Islamic movement which exalts Mirza Ghulan Ahmad, a religious leader from Punjab, British India who rose to prominence in the 19th century, as the Messiah and Mahdi – the metaphorical second coming of Christ. Believers of this branch of Islam are referred to as Ahmadi Muslims – named after the prophet Muhammad’s alternative name, Ahmad.

This year marks the return of Jalsa Salana UK after its 2-year gap due to the Covid-19 pandemic., though accompanied by various health and safety measures. It was held on the 5th to 8th of August at the Hadeeqatul Mahdi, hosting a total of 8,887 invitees – 6,709 and 2,168 men and women respectively; though this pales in comparison to the usual 35,000 Ahmadis it usually draws from around the world.

This year marks the return of Jalsa Salana UK after its 2-year gap due to the Covid-19 pandemic., though accompanied by various health and safety measures. It was held on the 5th to 8th of August at the Hadeeqatul Mahdi, hosting a total of 8,887 invitees – 6,709 and 2,168 men and women respectively; though this pales in comparison to the usual 35,000 Ahmadis it usually draws from around the world.

The invitees were chosen by ballot while 4,000 Muslims who were unable to attend gathered virtually at 40 mosques and centers across the UK to watch the Jalsa. This stands testament to how Jalsa Salana is the largest annual Islamic convention in the UK, having run for over 50 years and organized every year by the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community (AMC)

The invitees were chosen by ballot while 4,000 Muslims who were unable to attend gathered virtually at 40 mosques and centers across the UK to watch the Jalsa. This stands testament to how Jalsa Salana is the largest annual Islamic convention in the UK, having run for over 50 years and organized every year by the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community (AMC)

On each day, an address was given by the global Islamic Caliph of the AMC – Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad (aba), otherwise called Huzur by Ahmaddis. The Jalsa began with an inauguration, held at the Jalsa Gah – the stage and seating area where Huzur and attendees congregate. Here, Huzur affirms that while this year’s Jalsa might be small in size, it was nevertheless held to quench the spiritual thirst of the people and to allow those chosen to serve the guests of the Promised Messiah.

Through these addresses, Huzur commends the Jama’at’s great work – speaking of missionaries worldwide and testimonies from new believers. He speaks of the fruits of their labor, in the 211 mosques built, in the many new converts, in the numerous people reached through their publications and translations, and how connections between past and lost converts have been strengthened and rebuilt. He also details the good work done beyond the religious realm – speaking of their humanitarian and medical efforts in emergency situations worldwide.

Through these addresses, Huzur commends the Jama’at’s great work – speaking of missionaries worldwide and testimonies from new believers. He speaks of the fruits of their labor, in the 211 mosques built, in the many new converts, in the numerous people reached through their publications and translations, and how connections between past and lost converts have been strengthened and rebuilt. He also details the good work done beyond the religious realm – speaking of their humanitarian and medical efforts in emergency situations worldwide.

Yet, at the core of his addresses are spiritually riveting sermons – ones that expands upon the core teachings of Islam. In his address on the last day, he builds upon sermons from prior Jalsas, speaking of the rights of others and how Ahmadis should act in propriety of them. He speaks on the rights of friends, the sick, the orphans, oaths, and others during the war – reiterating the significance of duty, righteousness, and intention. In the end, he closes the address as usual and ends the convention with a silent prayer.

Featured throughout the convention are interviews and testimonies by the invitees, staff, and volunteers. Here, they recount the significance of the Jalsa and the very visceral experience which accompanies it. Often, they speak of Huzur as an awe-inspiring and close figure – one they hold a deeply personal relationship with.

The Huzur commands a powerful presence, one which invokes in Ahmaddi Muslims a spiritual and emotional experience. Beyond the teachings and sermons the Jalsa will impart them, the Jalsa presents Ahmaddi Muslims the privilege of being in his presence and the chance to serve and hopefully meet him.

The Huzur commands a powerful presence, one which invokes in Ahmaddi Muslims a spiritual and emotional experience. Beyond the teachings and sermons the Jalsa will impart them, the Jalsa presents Ahmaddi Muslims the privilege of being in his presence and the chance to serve and hopefully meet him.

This year Jalsa’s stands as a feat in and of itself – a large convention held during one of the most vulnerable and dangerous periods in history. According to Huzur, the organizers had initially believed that the Jalsa would not be held due to the current Covid-19 conditions.

This assumption would continue to spill over to affect the preparations of the Jalsa – leading Huzur to believe that the organizers were not doing it with full conviction. Worrying that the half-hearted conditions of the organizers would affect the volunteers and workers, Huzur had expressed his concern to them – jolting them into a greater sense of urgency despite delays in preparation.

Huzur recognizes the workers and volunteers as the true driving force of the Jalsa. He mentioned that while many were disappointed that they were not chosen to serve, those that were chosen had fulfilled their duty to their utmost conviction and would be thoroughly rewarded by Allah. Though faced with weather setbacks such as heavy rain, the volunteers came together to dirty their hands with great spirit in order to help the many struggling cars in the muddied parking lots throughout the tiring weekend – showcasing a great display of their conviction.