by Yvonne Tan

Language debates within Malaysia are almost always highly charged. From time to time the heated medium-of-instruction debate between Bahasa Malaysia vs. English Language for Maths and Science props up every so often. Be it from then Minister of Information, Communication and Culture, Rais Yatim sneering at a journalist “Saya tak jawab lah soalan begitu. Tanya je lah dalam bahasa kebangsaan […] Where were you educated? You can’t speak bahasa at all?” or when Sharifah Amani said “I sound like, stupid, if I speak Malay, so I’ll speak English” when accepting her Best Actress award at the Malaysian Film Festival (FFM). Lest we forget the discussions in Twitterjaya about why Malaysians continue to struggle with the common languages they have learnt in school be it English (aimed at Malays) and Malay (aimed at Chinese).

Nevertheless, one part of the language debate in Malaysia that does not have as much strife or even much focus on, is pride in regional dialects. They are almost always celebrated exclusively in alternative media and pop culture. Syahmi Sazli’s “drama spontan” and Alieff Irhan has made waves throughout YouTube for their use of Baso Kelaté or Bahasa Kelantan. Film has also taken a liking to utilising dialects such as Cun! (2011) a romantic comedy entirely in the Kedahan dialect starring several actors who were not necessarily native to Kedah but took the time to learn the regional dialect, many saluting Remy Ishak’s attempt. Others include Dain Said’s Bunohan (2011) and Budak Kelantan (2008) where both touch on urban-rural and development-tradition divide with a big dose of crime. Needless to say, Northern Malay dialects have drawn on and challenged stereotypes of rurality and backwardness as with films like Chemman chaalai (2005) and Jagat (2015) on the Malaysian-Indian community, both also filmed primarily in Malaysian Tamil.

Malaysian dialects have also been featured prominently within the growing hip hop genre in Malaysia. Artists such as K-Main, RxF Rhaled & YAPH – Golok, where many express pride in being Kelantanese while the famous Sabahan rap group K-Clique proudly mixes English with the Sabahan dialect alongside the inclusion of regional culture in their music videos from dances, festivals to everyday lorongs, warung and palm oil plantations. Fauxe, a Singaporean artist also mixes traditional samples from traditional Malaysian Tamil to Hawaiian Malay music overlayed with hip hop beats and distortions; a fusion serving as an ode to Malaysia and its sonic legacy.

Malaysian dialects have also been featured prominently within the growing hip hop genre in Malaysia. Artists such as K-Main, RxF Rhaled & YAPH – Golok, where many express pride in being Kelantanese while the famous Sabahan rap group K-Clique proudly mixes English with the Sabahan dialect alongside the inclusion of regional culture in their music videos from dances, festivals to everyday lorongs, warung and palm oil plantations. Fauxe, a Singaporean artist also mixes traditional samples from traditional Malaysian Tamil to Hawaiian Malay music overlayed with hip hop beats and distortions; a fusion serving as an ode to Malaysia and its sonic legacy.

Hip hop was especially popular during block parties in the 70s, creating a space for multicultural exchanges between African-Americans and other immigrant and marginalised communities, with many rappers having Latin American or Caribbean origin. Hence, hip hop naturally reflected their shared socioeconomic background as well, providing an outlet to be proud of hybrid cultures that are not necessarily celebrated elsewhere. Although not in a dialect, Kidd Santhe’s Bawah is a song that captures this essence, albeit localised, with the lyrics “berapa kali polis tahan budak india tak lepas, hari-hari kena gari buat cam barang hias”.

If English signifies professionalism/internationalism and Bahasa Melayu as loyalty to the nation [1], then regional dialects signifies the specific community one comes from. Unlike English and Bahasa Melayu, usually framed as a “choice” to become fluent, dialects don’t have a similar connotation. Given they are not as accessible such as tonal accents cannot simply be ‘learnt’, dialects require living for a long time within the community. Almost always, dialects never exist on their own, with subtitles in Malay or English to try to bridge the gap and ensure a wider audience, important to alternative media platforms.

Not only in Malay communities but also within others, with the prominence of Mandarin, there has been some worry of how “dialects” like Hokkien, Hakka, Cantonese, Teo Chew and so on would be phased out. Hong Kong protests consistently emphasize that Cantonese is not a dialect but a separate language altogether as mutually unintelligible to Mandarin, resisting standardisation. The same can be said with Taiwan so much so with the Sunflower Student Movement, indie band Fire Ex’s Island’s Sunrise song in Hokkien became the anthem. The same pride in such dialects has also trickled here as well such as Hai Ki Xin Lor [You Mean the World to Me] is a film entirely in Penang Hokkien, a first for Malaysia. Meanwhile, Cantonese has been regularly featured in films that proudly mix languages together such as Fly By Night (2018), Ola Bola (2016) and the Sepet trilogy.

An Instagram filter “Guess the Gibberish: Malay edition” is a play on the Gibberish challenge, where English words were used to mimic Malay slang and people had to make out what the Malay phrase was. For example: people had to guess “low lung sea low mat tea” as “lu langsi lu mati” and my personal favourite “nah see go rank tell lure matter” as “nasi goreng telur mata”.

Regionalised ones popped up soon after such as Penang, Kedah, Negeri Sembilan and so on with netizens becoming popular for guessing and commenting with the filter. Multilingualism is required to utilise the filter where, depending on which filter, knowledge of English and Malay or the regional dialect.

Regionalised ones popped up soon after such as Penang, Kedah, Negeri Sembilan and so on with netizens becoming popular for guessing and commenting with the filter. Multilingualism is required to utilise the filter where, depending on which filter, knowledge of English and Malay or the regional dialect.

Linguistic uniformity has almost always been favoured by nation-states while others mourn the death of many dialects worldwide. Nevertheless, what is unique about the increasing vernacular popular culture in Malaysia is the awareness of an audience beyond the community, almost always accessible to a Malaysian audience and expanding the three labels of “Malay” speaking standard Malay, “Chinese” speaking Mandarin, “India” speaking Tamil. This runs counter to how dialects are usually used, more often than not as an “indirect and intellectually respectable way of defending the borders, those outlying borders crossed by foreigners”. [2]

However—as popular and official discourse have always been conceptually distinct—the growing conscious use of dialects within the Malaysian context has seen the reimagining of “national” sentiments as language of diverse groups can exist and be celebrated. Despite increasing migration and urban centralisation, popular culture has often been, and continues to be, associated with unmediated oral vernacular culture which serves as a rare source of pride and optimism in the never-ending language strife within Malaysia.

*Special thanks to Fuad Rahmat for keeping me updated with Hip Hop in Malaysian dialects

[1] Tan Zi Hao, “Language shaming in Malaysia” New Mandala, 19 January 2017

<https://www.newmandala.org/language-shaming-malaysia/>

[2] Michael North The dialect of modernism: race, language, and twentieth-century literature. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994, p. 25.

Projek Dialog is embarking on ‘Leveraging Media for Advocacy Objectives,’ a six-month research project on politically effective social media usage. We are looking for dedicated research assistants to help to facilitate surveys, analyze data and manage social media platforms for strategic outreach on intercultural understanding.

Projek Dialog is embarking on ‘Leveraging Media for Advocacy Objectives,’ a six-month research project on politically effective social media usage. We are looking for dedicated research assistants to help to facilitate surveys, analyze data and manage social media platforms for strategic outreach on intercultural understanding.

As the identities of the officers were released, Tou Thao, an Asian American officer who had stood by as his colleague restrained and eventually killed George Floyd became another subject of discussion on anti-blackness within Asian communities. As the model minority myth is perpetuated about Asian American immigrants, it further justifies mistreatment of other minority groups including African and Latin American communities which is in itself an opportunity to touch on the once transnational dream of African-Asian solidarity.

As the identities of the officers were released, Tou Thao, an Asian American officer who had stood by as his colleague restrained and eventually killed George Floyd became another subject of discussion on anti-blackness within Asian communities. As the model minority myth is perpetuated about Asian American immigrants, it further justifies mistreatment of other minority groups including African and Latin American communities which is in itself an opportunity to touch on the once transnational dream of African-Asian solidarity. Grace Lee Boggs, who was mistaken by the FBI as an “Afro-Chinese”, personified her arguments against any approach that would focus singly on either race or class: “Whether the [March on Washington] movement proves transitory or develops into a broad and relatively permanent movement for Negro democratic and economic rights will depend upon whether it will develop a leadership which seeks its main support in the organized labour movement and whether the Negro masses in the labour movement are ready to enter into and actively support this

Grace Lee Boggs, who was mistaken by the FBI as an “Afro-Chinese”, personified her arguments against any approach that would focus singly on either race or class: “Whether the [March on Washington] movement proves transitory or develops into a broad and relatively permanent movement for Negro democratic and economic rights will depend upon whether it will develop a leadership which seeks its main support in the organized labour movement and whether the Negro masses in the labour movement are ready to enter into and actively support this

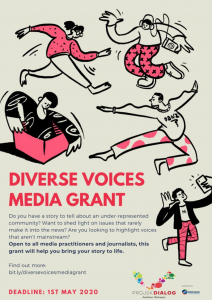

When we first put a call out for grant submissions, we were expecting diversity. But even so, we were surprised at how extensive the diversity in media could be.

When we first put a call out for grant submissions, we were expecting diversity. But even so, we were surprised at how extensive the diversity in media could be. The selection process involved an individual evaluation, where each member of the selection committee received access to all the submissions and assessed them individually, as well as a group evaluation where all selection committee members met to discuss the final 10.

The selection process involved an individual evaluation, where each member of the selection committee received access to all the submissions and assessed them individually, as well as a group evaluation where all selection committee members met to discuss the final 10. Proses pemilihan melibatkan penilaian individu, di mana setiap ahli jawatankuasa mempunyai akses kepada semua permohonan dan penilaian secara berasingan dijalankan. Selain itu, penilaian secara berkumpulan juga dilaksanakan di mana semua ahli jawatankuasa pemilihan bertemu untuk membincangkan 10 finalis.

Proses pemilihan melibatkan penilaian individu, di mana setiap ahli jawatankuasa mempunyai akses kepada semua permohonan dan penilaian secara berasingan dijalankan. Selain itu, penilaian secara berkumpulan juga dilaksanakan di mana semua ahli jawatankuasa pemilihan bertemu untuk membincangkan 10 finalis.