by Yvonne Tan

Before the pandemic, like every other Malaysian, I would frequent the same mamak at all times of the day. Eventually the workers recognized me, and they too also remembered my friends that tagged along. However, after some time the workers themselves started disappearing one by one and never returned. When my friend prompted one of the remaining workers we recognized about where the rest went, there was only a short reply “kena tangkap” before it got awkward and moved on to our order.

There is no need to stress the cultural significance of mamak in Malaysia. Hailed as an everyman restaurant in proximity to just about anyone’s home and workplace, a relaxed atmosphere any time of the day and also an exemplar of Malaysia’s multiculturalism that celebrates the “inadvertent space for cosmopolitan togetherness by facilitating our enactment of a seemingly banal collective national pleasure and pastime: our love of food and eating” [1]. However, just as food plays a social role in bringing communities together, it also divides of which the latter we have yet to reckon with including the high cost to sustaining food identities only for the government-mandated three races. [2]

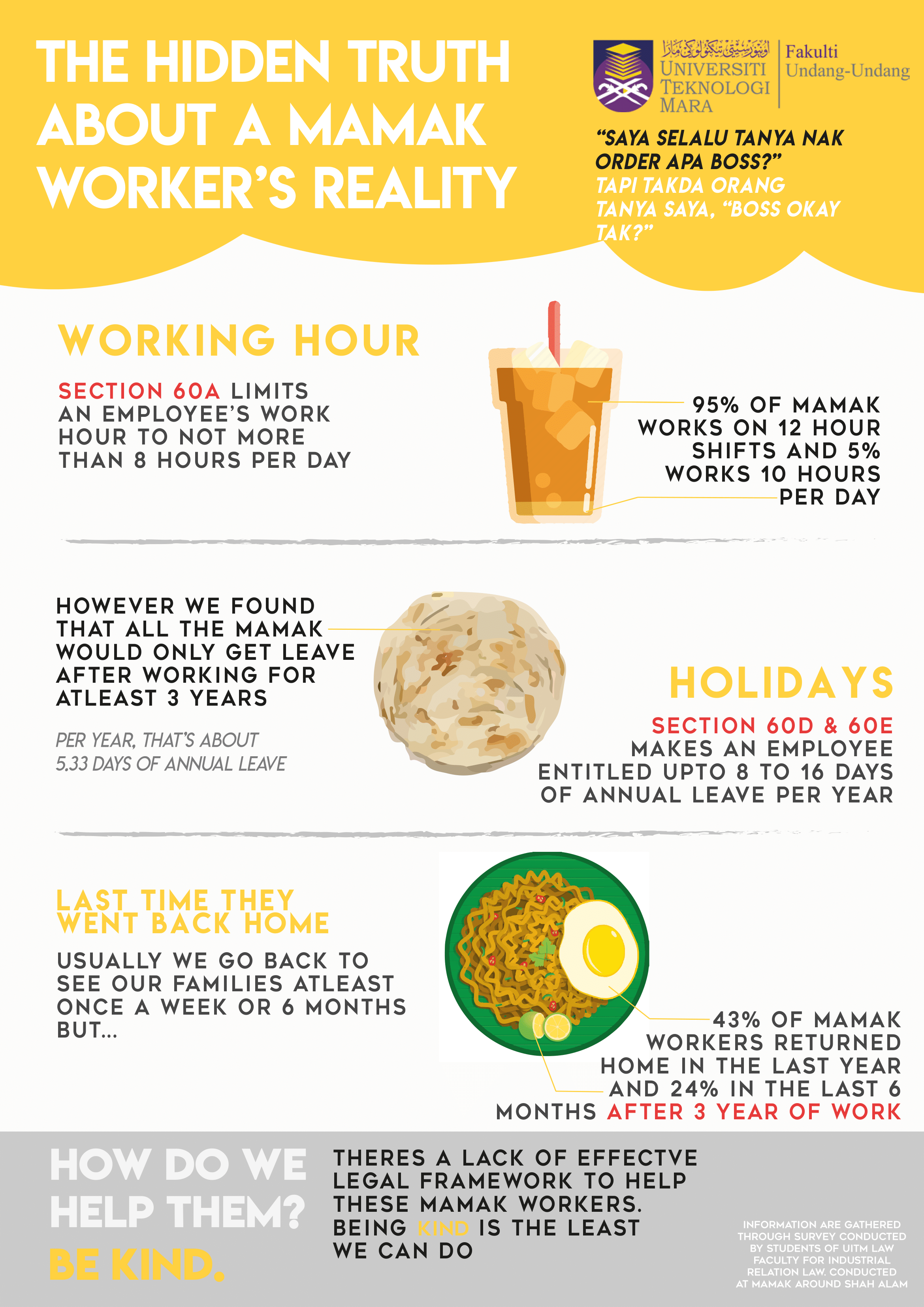

A UiTM study for a course assignment in January 2021 had conducted a small study of nine mamak stalls in Shah Alam took to social media to share their findings which eventually became viral on Twitter. The study showed that most workers in the mamak worked shifts of up to 12 hours a day with no overtime pay, no annual leave for at least 3 years and that abuse is rarely reported. It was also one of the first few times popular discourses on mamak was not simply about a special roti canai they had or how cheap the food was but rather how exploitative the business model was, and recognized that it was mostly run by exploited foreign workers despite being a hub of national pride.

A UiTM study for a course assignment in January 2021 had conducted a small study of nine mamak stalls in Shah Alam took to social media to share their findings which eventually became viral on Twitter. The study showed that most workers in the mamak worked shifts of up to 12 hours a day with no overtime pay, no annual leave for at least 3 years and that abuse is rarely reported. It was also one of the first few times popular discourses on mamak was not simply about a special roti canai they had or how cheap the food was but rather how exploitative the business model was, and recognized that it was mostly run by exploited foreign workers despite being a hub of national pride.

The infographic also calls to be more understanding towards workers via the question “How to help them? Be kind”. As the initial assignment was to investigate the level of public awareness on the Malaysian Employment Act 1955 which prohibits such practices, the reality of upholding such protections is very different. This is of course not the first feature of mamak stall’s abusive labour practices. BBC’s feature story back in 2011 titled “Malaysian business’ labour dilemma” reported that workers had regular 16-hour shifts and still had to eventually close down most of its locations because of a shortage of foreign workers given the government had rejected their application for more Indian workers in an attempt to reduce the reliance on cheap labour while little is done to protect the rights of migrant workers.

Mamaks that get exported elsewhere consistently faced fines for breaching labour laws such as Mamak Pty Ltd in Sydney was fined twice for underpaying staff and allegedly forging false records to hide underpayments, however, the company was liquidated during the court case with an AUSD 1.3 million tax bill. New Naratif had also reported on the unsustainability of Singapore’s hawker model which has been made a “cultural institution” by the government with UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity recognition. Without opportunities to truly be equal members of Singaporean society via the hawker profession, with 12 to 14 hour working hours, more often than not 6 days a week, our neighbours also lament their diminishing hawker culture.

Lim in the article critiques the unpremeditated national celebration of systems unfavourable to hawker workers: “Yet we embrace and perpetuate a social and economic system that is essentially spawning more jobs like this [Business Development Managers], and that keeps Singaporean wages competitive partly by keeping the price of hawker food low, with the result that hawkers are driven out of the profession”. Lim’s critique has striking similarities to the food sector in Malaysia which has been supported by corruption and exploitation in our immigration and labour systems, but we too continue to welcome this system to ensure the price of hawker and mamak food remains low.

It is as Muniandy aptly describes “communities and individuals become enrolled as surplus within the capitalist economy – they serve the function of increasing profit margins, thanks to the devaluation of their lives and reduction as human waste, desperate to work at any cost, whose bodies become easily replaceable by the availability of more surplus populations.” [3]. Although the identity of mamak stall has always been rooted in migration, and celebrated as our national identity, it is but in a deeply exploitative setting where migrant workers are praised for doing a job that no Malaysian would do given the harsh working conditions.

And it has only gotten worse with the new wave of raids on migrants following MCO 3.0 where videos of authorities spraying disinfectant spray on them became viral and a now-deleted tweet featuring a poster by the Malaysian Immigration department stated: “Migran Etnik Rohingya Kedatangan Anda Tidak Diundang”. One of the recent images that surfaced during the raid was a man wearing a black “I Love KL” T-Shirt illustrating the poignancy of Malaysia’s intolerance despite being the highest recipient of migrant workers in Southeast Asia.

And it has only gotten worse with the new wave of raids on migrants following MCO 3.0 where videos of authorities spraying disinfectant spray on them became viral and a now-deleted tweet featuring a poster by the Malaysian Immigration department stated: “Migran Etnik Rohingya Kedatangan Anda Tidak Diundang”. One of the recent images that surfaced during the raid was a man wearing a black “I Love KL” T-Shirt illustrating the poignancy of Malaysia’s intolerance despite being the highest recipient of migrant workers in Southeast Asia.

Hence, let us reassess the identity of the mamak which has become the exemplar of food as both a point of national unity and division. Lauded as democratic and popular spaces for multiculturalism when turning a blind eye to the plight of the migrant workers operating such stalls, the pandemic has amplified this divide. As memes of missing mamak food proliferate while another mass immigration crackdown is carried out, it is a dichotomy that we should reconcile with. Malaysian food continues to be a point of national pride for most of us and as empathy can be a starting point, there is a need to demand for change to the precarious systems that will eventually result in the end of such establishments with efforts by authorities every so often to curb “social ills” such as “concerns that the young spend too much idle time in such places and get involved in unhealthy activities […] besides being favourite haunts for foreign immigrants”.

Hence, let us reassess the identity of the mamak which has become the exemplar of food as both a point of national unity and division. Lauded as democratic and popular spaces for multiculturalism when turning a blind eye to the plight of the migrant workers operating such stalls, the pandemic has amplified this divide. As memes of missing mamak food proliferate while another mass immigration crackdown is carried out, it is a dichotomy that we should reconcile with. Malaysian food continues to be a point of national pride for most of us and as empathy can be a starting point, there is a need to demand for change to the precarious systems that will eventually result in the end of such establishments with efforts by authorities every so often to curb “social ills” such as “concerns that the young spend too much idle time in such places and get involved in unhealthy activities […] besides being favourite haunts for foreign immigrants”.

References

[1] Duruz, Jean, and Gaik Cheng Khoo. Eating together: Food, space, and identity in Malaysia and Singapore. Rowman & Littlefield, 2014, p. 68.

[2] Perry, Melissa Shamini. “Feasting on culture and identity: Food functions in a multicultural and transcultural Malaysia.” 3L: Language, Linguistics, Literature® 23, no. 4 (2017): 184-199, p 186.

[3] Muniandy, Parthiban. “From the pasar to the mamak stall: refugees and migrants as surplus ghost labor in Malaysia’s food service industry.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46, no. 11 (2020): 2293-2308, p. 2305.