by Yvonne Tan

We are no stranger to anxieties surrounding halal consumption practices and the danger of contamination making waves in the media with a variety of non-halal spaces available. Back in 2014, there was the Cadbury Dairy Milk chocolate scare where initial tests by Health Ministry (KKM) found traces of pork DNA before JAKIM did another round of tests to dispute this. Long story short, a boycott soon followed suit and the two products where traces of pork were found in was withdrawn. The Year of the Dog and the Pig on the Chinese Zodiac lunar calendar meant the animals were going to be depicted in decorations, advertising and so on for the New Year Celebrations.

If you thought that the problem with “babi” was confined to Malaysia alone, well think again. Who could forget when Dua Lipa’s Instagram caption caused a fiasco among Malaysians for wishing her father happy birthday, calling him “babi” as it meant dad in Albanian. After being mocked for using the word by Malaysians, she edited the caption as to “Happy Birthday Dad”. In a similar instance, a K-pop dancer coincidentally named Babi had received the same treatment. She responded differently releasing an angry statement on Instagram as well to Malaysians stating “I am not interested in your language, so it doesn’t matter what my name means in your language. And I didn’t know your country, but I don’t want to know it anymore.”

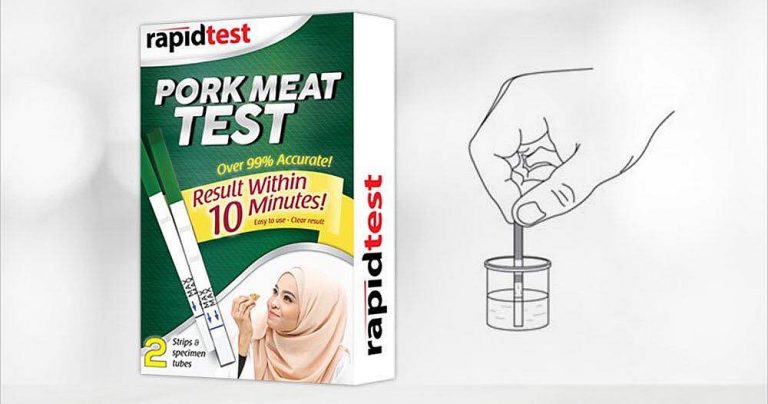

Iftitah Solutions (M) Sdn Bhd, owner of the brand Rapidtest released a product in 2019 called Pork Meat Test that claims to be able to detect pig DNA content in food, delivering results with 99% accuracy within 10 minutes. It was eventually written off by JAKIM, stating that this might lead to confusion and that authorities should be left to handle enforcement of halal products.

Iftitah Solutions (M) Sdn Bhd, owner of the brand Rapidtest released a product in 2019 called Pork Meat Test that claims to be able to detect pig DNA content in food, delivering results with 99% accuracy within 10 minutes. It was eventually written off by JAKIM, stating that this might lead to confusion and that authorities should be left to handle enforcement of halal products.

This time around it involves OLDTOWN White Coffee, where a TikTok user @sazz999ritz accused the restaurant of using pork meat in their Mee Kari. Quickly many defended OLDTOWN stating they were halal-certified by JAKIM to acknowledging that there is a common fear that Chinese people are out to contaminate food consumed by Malay Muslims. Another debate that arose was the expensive price of pork itself as a reason that Chinese people do not have an incentive to switch out a chicken product for pork. Some poked fun upholding this reasoning using the Chinese stereotype that they are “kiam siap”.

Meanwhile headlines from throughout the media ranged into two camps from “Restoran Halal terkenal jual mi kari babi”, “Oldtown White Coffee nafi produk mengandungi daging babi” to “Responsible Netizens Call Out Fake News After OLDTOWN White Coffee Accused Of Serving Pork Instead Of Chicken”. Ministry of Domestic Trade and Consumer Affairs (KPDNHEP) took the complaint seriously and did an inspection under Perintah 3(1)(a) Perihal Dagangan (Takrif Halal) 2011. They checked their halal certification to the ingredients itself while JAKIM confirmed that their Mee Kari were halal.

While some rushed to support OLDTOWN’s food, this continued to raise some eyebrows across Twitterjaya. Comments included that it was always better to eat at a Malay Muslim establishment without a JAKIM halal certification rather than one own and operated by a Chinese with certification, further signalling a distrust in the audit process in securing halal consumption. As the OLDTOWN controversy died down, another came around.

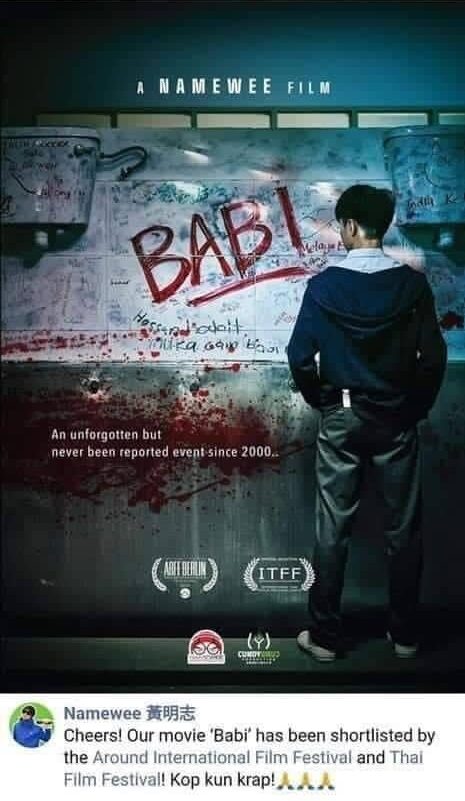

Namewee, who is no stranger to controversies since his parody of Negarakuku, is once again at the center of public attention for his film conspicuously named Babi. After Namewee celebrated his international nominations at the Open World Toronto Film Festival, Around International Film Festival and Thai Film Festival the Perikatan Nasional Youth lodged a report specifically against the film’s poster. It featured a vandalized wall of a toilet with words like “Cina babi” other racial slurs such as “Melayu B-“ and “Indian K-“, not revealing the full derogatory slur of the other races. Namewee claimed the film was banned in Malaysia and is based on an alleged race-war that started innocently in a Malaysian high school in 2000 and covered up.

Namewee, who is no stranger to controversies since his parody of Negarakuku, is once again at the center of public attention for his film conspicuously named Babi. After Namewee celebrated his international nominations at the Open World Toronto Film Festival, Around International Film Festival and Thai Film Festival the Perikatan Nasional Youth lodged a report specifically against the film’s poster. It featured a vandalized wall of a toilet with words like “Cina babi” other racial slurs such as “Melayu B-“ and “Indian K-“, not revealing the full derogatory slur of the other races. Namewee claimed the film was banned in Malaysia and is based on an alleged race-war that started innocently in a Malaysian high school in 2000 and covered up.

By now, it is clearer that these outrages are from the cultural politics of food risk as informed by race and religion. Babi is the abject other not only because it is considered to be haram and against the Malay Muslim identity but that “it lies there, quite close, but it cannot be assimilated” given how esteemed pork is to the Malaysian Chinese identity. It has become the defining factor of what demarcates and distinguishes oneself from the opposite of oneself. This cultural narrative that babi is a threat that one will continuously be confronted by given the presence of an identity that celebrates pork, has thus been passed down.

The disgust and uneasiness associated with babi “is thus not the lack of cleanliness or health that causes abjection but what disturbs identity, system, and order. What does not respect borders, positions, rules. The in-between, the ambiguous, the composite”. [1] When the clear distinction is no longer there, there is outrage as it threatens what is thought to be the core of one’s identity–in this case is Islam–which the nation-state is supposed to be structured on.

In the case of OLDTOWN, it highlights increasingly there is a wider rupture in food trust with Malaysia Halal Certification under the purview of JAKIM. Thus, this ambiguity calls for people to take things into their own hands such as with Rapidtest, choosing to support specifically Malay Muslim establishments or eating at a restaurant situated far from a Chinese restaurant in fear of pork particles travelling through the air.

People have become cynical to the halal certification process where “officials would request cash payments above the statutory fees in order to guarantee registration. Municipal councils and the fire department, too, would request such payments to issue the necessary documents required by JAKIM for halal product and premises applications.” [2] It has become but the norm with the high rates of rejected applications, lack of quality control officers, the proliferation of fake halal certificates with JAKIM having total purview on the matter.

Calling out corruption practices only leads to backlash such as the now-deleted allegations against JAKIM for purposely delaying the restaurant’s halal certification to for a bribe. Hence, such seemingly “drastic” measures to ensure one’s food is halal may stem from recognising JAKIM’s ineffectiveness and in the process avoiding establishments that have no personal incentive to be halal. The quick response by the government in order to ensure the dish was indeed halal after the video went viral is also a display of the effectiveness of their agencies in ensuring there is no food risk.

During the OLDTOWN controversy, there was some discussion on what is considered “haram” is always more or less exclusive to only to pork and the specific usage of “babi”. Bringing up that there is no equal outrage with corruption which is equally if not more haram. A particular video with an unknown source was circulated during this time where a man speaks about how the idea that dogs and pigs are haram are instilled since birth and wished people saw corruption as something more haram as it affects more than one person.

Not to mention, as noted earlier, recurring controversies surrounding babi are not confined only to whether a food is halal or haram but a need to make this term exclusively forbidden, calling out international figures who have no knowledge of the term in Malaysia. Eventhough “pig” is a derogatory term elsewhere, there is an added quality babi holds that no exceptions can be made for the word to mean something else only reveals how much weight the term holds and also how much of a national preoccupation it is.

In this regard, the word provokes shock and disgust to the point one is unable to look beyond its set-in-stone meaning and understanding of other cultures. Babi is the antithesis of what rojak / kebudayaan rojak is. While babi is a point of contention, representing lack of compatibility between cultures and uneasiness about not observing Islamic law with the cultural disparity, rojak on the other hand “constitutes a useful set of images for reflecting on the politics of commensality, intercultural exchanges, and identity hybridity and belonging”. [3]

[1] Kristeva, Julia. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. Translated by Leon S. Roudiez. Columbia University Press, 1982. p. 1, 4.

[2] Duruz, Jean, and Gaik Cheng Khoo. Eating together: Food, space, and identity in Malaysia and Singapore. Rowman & Littlefield, 2014p. 2.

[3] https://www.themalaysianinsight.com/s/189692