by Yvonne Tan

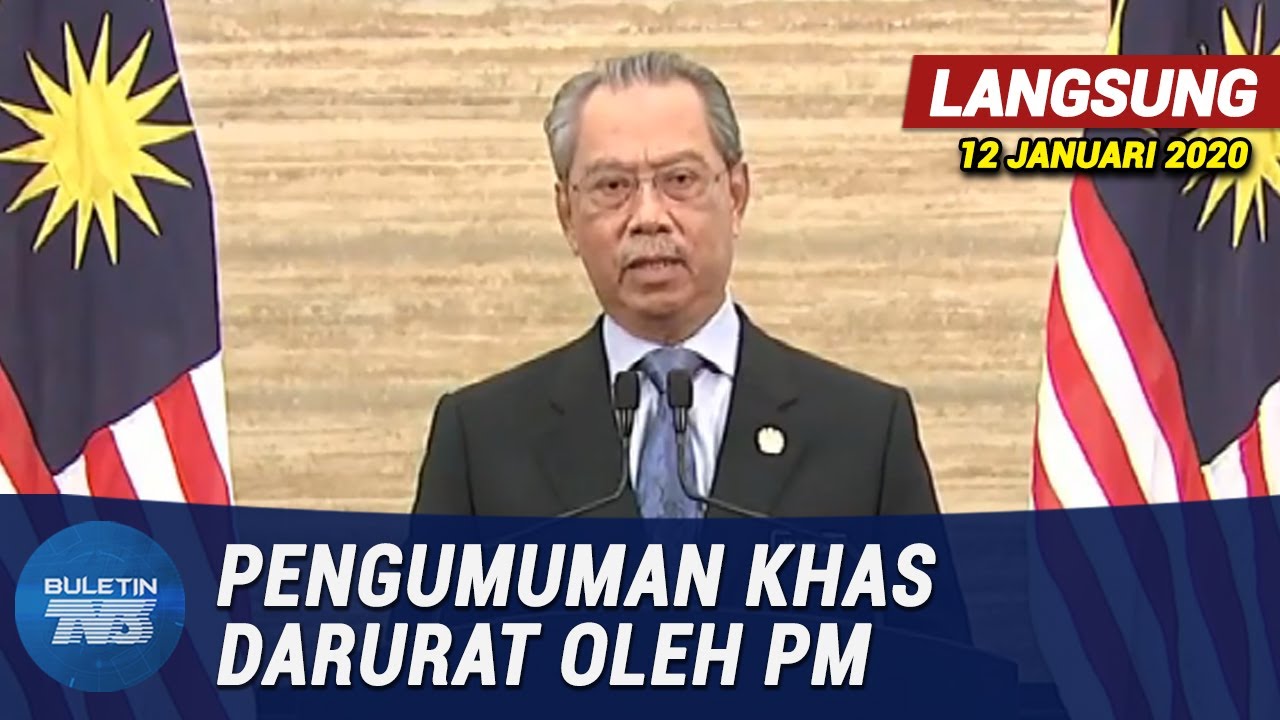

“How are you? I wish you all in the best of health always.” was how Muhyiddin began his special announcement of Emergency. On the contrary of Muhyiddin’s personable opening, darurat has always been a term that invokes fear, conjuring up real memories of curfews and stockpiling goods that ensued after the May 13 riots or throngs of army officers arriving for military confrontation during Darurat Malaya.

There may have been other instances of darurat such as for haze or other political crises, but these two moments of history inform most our concept of darurat. Listicles of previous instances of darurat appeared soon after darurat was proclaimed and also how this darurat would be different, stressing how it would make very little difference to one’s life.

Political artists Fahmi Reza and Zunar illustrated what many believed darurat was used for – a political manoeuvre. Fahmi Reza’s work drew Muhyiddin as a clown, like he did infamously with Najib but with Thanos’ infinity gauntlet. Meanwhile, Zunar created a “Fahami Darurat” series which criticizes Muhyiddin’s priorities. Clearly stating darurat only benefits himself, he plays on the word “Check and Balance” to “Cheque and Balance”.

Political artists Fahmi Reza and Zunar illustrated what many believed darurat was used for – a political manoeuvre. Fahmi Reza’s work drew Muhyiddin as a clown, like he did infamously with Najib but with Thanos’ infinity gauntlet. Meanwhile, Zunar created a “Fahami Darurat” series which criticizes Muhyiddin’s priorities. Clearly stating darurat only benefits himself, he plays on the word “Check and Balance” to “Cheque and Balance”.

Others were more hopeful that this darurat would be different. Ex-Deputy Defense Minister Liew Chin Tong in his op-ed for South China Morning Post, spoke about the now faded hope of Malaysia Baru in 2018, “If there is anything to hope for, Malaysia in 2021 is not 1969. There is a huge population of swing voters who have high expectations of the government and who would not tolerate the return to one-party state authoritarian rule.” Others who also have hope in “the people” include Affendi Salleh wrote a poem titled “Proklamarah”. After the government’s repeated call for the public to not panic and be still “wabak meroket: tenang, Gelombang kedua sebab kerja khianat: tenang” before proposing that the solution is to do the opposite – causing disturbance:

Tapi apa pilihan yang ada.

Sebab opposite kepada tenang ialah kacau.

Kacau.

Yang rhyme dengan lancau.

What made this darurat different was how it caught us off-guard after darurat had been called off on October 23 2020. Then, many sources reported that Muhyiddin was due to present the proposal to the King, providing a small window of opportunity for many to air their disagreements. However, the first day of darurat this time was preoccupied with the trademarking of the Harimau Menangis dish which would affect small business owners selling the dish and “Hotpot Datuk” who was caught on camera assaulting a couple at a hotpot restaurant. The day after, comments by Nala designer on went viral, in particular on how she wanted to see the baju kurung return.

Although in each case there were surely well-founded justifications for outrage, they seemed to have overshadowed the fact that our democracy has been put to a stop. Maybe we are unable to deal with another political setback that we are once again forced to sit back and watch idly by or maybe we know all too well the demoralization of defeat that will certainly come after staging a rebellion against the state.

The criticism against Datin Noor Kartini Noor Mohammed, Lisette Scheers, Datuk Kwan Foh Kwai by internet users are usually labelled as part of the toxic social justice warrior trend. However, I would like to recall James Scott’s Weapons of the Weak (1985) which shed light on everyday forms of peasant resistance in Sedaka, Kedah. Usually, there is little to no planning or coordination, presenting a form of individual self-help and withdrawal rather than institutional confrontation. These everyday forms also typically avoid any direct confrontation with authority or elite norms.

The practices slowly and silently wear down the power of the powerful, and perhaps even serve as a rehearsal for open confrontation. Although criticisms by netizens are not exactly the same as what Scott argues as between “the peasantry and those who seek to extract labour, food, taxes, rents and interest from them” [1], there are key similarities. The recent events take on the same form as the outrages against Vivy Yusoff and Aleeya Zailan, ridiculing upper class for their unacceptable and tone-deaf actions.

The first day of darurat, netizens criticized the impact of Datin Noor Kartini Noor Mohammed’s trademark on the B40 and promoted variations of harimau menangis by small businesses in response. There were also a clear consensus that it was a greedy act of capitalizing during a difficult time. Similarly, Lisette Scheers’ comments that seemed hypocritical given she lamented the commercialization of Kuala Lumpur in which she contributes to with her highly-priced baju kurungs. This was also followed by people promoting small, local businesses as well who created baju kurungs at a much more affordable price. Datuk Kwan Foh Kwai had his datukship questioned and also many called for the police to intervene.

The first day of darurat, netizens criticized the impact of Datin Noor Kartini Noor Mohammed’s trademark on the B40 and promoted variations of harimau menangis by small businesses in response. There were also a clear consensus that it was a greedy act of capitalizing during a difficult time. Similarly, Lisette Scheers’ comments that seemed hypocritical given she lamented the commercialization of Kuala Lumpur in which she contributes to with her highly-priced baju kurungs. This was also followed by people promoting small, local businesses as well who created baju kurungs at a much more affordable price. Datuk Kwan Foh Kwai had his datukship questioned and also many called for the police to intervene.

There are clearly class undertones to these “online dramas” which led to all three apologizing. It can be analyzed through Scott’s lens that these subtle and nuanced continuous activities like grumbling, gossip, sabotage create a culture of resistance in which people rebel against the material superiority of the rich. Hence, Malaysians know full well that the romance of national liberation on May 9 did not work out and is now replaced with a more hegemonic and restrictive state, putting to rest ideas of open confrontations and uprisings.

As mentioned earlier, darurat continues to invoke deeply distressing memories. Hence, maybe opting for “everyday forms of resistance” which takes the form of sustained online criticism against the problematic actions of the upper class and their lack of understanding on the difficult time experienced by the majority is how we are currently dealing with martial law. It is as whenever Azmin Ali tweets something harmless or posts a simple greeting on Instagram, he will immediately get a barrage of comments calling him a pengkhianat until today. The uproar is not an all-out confrontation with the government as “because one side, the poor, is under no illusions about the outcome of a direct assault.” [2]

Notes

[1] James Scott, Weapons of the weak: Everyday forms of peasant resistance. Yale University Press, 1985, p. 29.

[2] Ibid, p. 22.