By Ahmad Fuad Rahmat

Triggered

Now is not the time for the rich to complain about how difficult they have it. That is what Aleeya Zailan and Vivy Yusoff is learning the hard way.

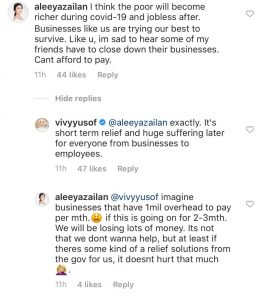

It all began when Aleeya remarked, in obvious reference to Bantuan Perihatin Nasional (BPN), that the B40 will be rich during the Covid crisis while businesses will struggle. The subtext could not have been more offensive. She is implying that the poor are benefitting from the lockdown. Vivy Yusoff, seemingly unbothered by the implication, agrees with Aleeya’s post by saying that this will be bad for everyone.

The posts that sparked the prairie fire.

It is unfair to make much of offhand comments but that’s exactly what happened. In the ensuing days the two were widely chastised by the internet for disregarding the plight of the poor. Various celebrities (Hairul Azreen and Shaharnaaz Ahmad among them) have spoken in Vivy and Aleeya’s defense but to little avail. The general consensus is to support the poor.

Aleeya’s bumbled justification for what she said saw her mocked even more. But the hate Vivy Yusoff is receiving is particularly venomous. A petition on Change.org calls for her removal from the UiTM board. It received over 6,000 signatories in less than a day. Her quick apology was followed by posts by Fashion Valet offering discounts. But her concession was taken as a sign of weakness as netizens continued to attack her. Everything, from her alleged inability to speak Malay to her expensive Tudungs, became fair game.

Ashraf Ariff weighed in using classic class-war rhetoric: “Alhamdulillah. This coronavirus will eventually reset the wealth gap between the rich and the poor and we won’t have to read nonsense like this anymore”

Meanwhile another class debate brews in the local entertainment industry.

This sparked when a few celebrities were calling for government aid. This is not unwarranted given how generous the BPN is. Malay artistes after all were struggling even before the lockdown. Now with no shows to do or products to promote they are left with no source of income.

But what was rendered as an earnest plea soon generated widespread ridicule. There were the usual charges: Malaysian artistes are out of touch with the masses, they have enough social capital as it is without making this crisis about them etc.

But what does stand out in the chorus of discontent is the assertion that celebrities deserve it because they had been faking their wealth this entire time anyway: It is their fault that they cannot realistically keep up with the lifestyle that had been posing for. Where the Malay masses were willing to play along in celebrity worship before, the crisis has now unmasked all pretensions.

Class is king

Twitter is seeing a populist explosion of class discourse unlike ever before and the fault-line between poor and rich Malays have never been more pronounced.

It is somewhat expected, however, that this would be sparked by media personalities. Malay popular culture – its constellation of films, TV shows, tabloids, influencers and social media-platforms – has always been fruitful grounds for class critique. Plot-lines about migrating to the city, the constant search for work, parodies of the rich have always trailed the slow but certain embourgeoisement of the broader Malay context since Independence. It is obvious in the classics of the Malay cinematic canon as it is in everyday TV dramas and cringey b-rated films.

These narratives generally holds little appeal to the intelligentsia who in their purported refinement turn to Western political theory for their class analysis. But Malay pop culture has the more important effect of being immediate and earnest: The message is that rich people are bad and the ones are who left behind will have the moral victory. It remains loyal to the problem in ways that ‘high-art’ or literature festivals generally have no interest in.

Thus the lesson of the week is that national discourse in the wake of Makcik Kiah and the B40 is clearly providing a much needed corrective to the perception – widely held even by Malay leftists – that ‘Feudal’ Malays are too comfortable with hierarchy. Class resentment – bitter self hatred against their own misfortunes but also more obviously against the Feudal and NEP rich – is mainstream.

B40

What is unprecedented though is that this divide is being articulated in straightforward terms. The class war is between between the B40 and the T20. I doubt there’s much concern as to their statistical particularities and that is beside the point. The ‘divide’ now has been broken down to catchy punchy categories. It’s tweetable, something readily churned by the slightest move of the fingertips.

But more than that they are realistic. Globally, occupy ran with the 99% forgetting that this number came out of American statistics where inequality reached utterly wretched levels. Malay capitalism, which is at best fifty years old give or take, is still in formation and the few who have benefitted from it are rarely so uprooted from their background as to be untouchable. The fate of its commercial class, which is in any case was artificially invented by the state, can be easily thrown into question precisely because its heyday from the late 80s to the mid 90s was only ever short-lived.

That Malay dramas are all too frequently centred on the question of which son will inherit the business speaks to the ever pervasive suspicion that Malay capitalism does not quite have a future. This anxiety, needless to say, is turning out very likely as a swift way out of Covid is looking more improbable by the day.

Anyway, this is why the discourse of inequality in Malaysia, or in this case, among Malays, is often more cultural than economic. Being well-off is about the extent to which you no longer recognise those you leave behind, or how much English you use, or where you studied and how you are rooted to your family etc. Being well off in other words is always stressed as an ephemeral thing, something of recent history, rather than a timeless place.

This is therefore not misplaced grievance because it underscores the basic premise that privilege is not reducible to income. Privilege is how one benefits from a system and for as long as a political system is imbued with culture, culture will also be evoked and deployed when privilege is resisted. Cultural capital goes both ways. People evoke it when it works for them or they use it against others for advantage. The same applies for how ‘culture’ – and this word applies of course too popular ‘low’ culture – is positioned in the Malay case.

Prihatin

But the most interesting development out of this debate is that the B40 are actually speaking out. They are, to use woke parlance, ‘owning’ their label. Rather than to be reduced to a statistical problem (technocrats have only spoken of them as the obstacle to Malaysia’s high income wet dream) they have come out as the privileged segment of the population.

The reason for this of course is none other than Muhyidin Yasin. Whether intentional or not, his speech resonated with the perennial ‘problem demographic’ of Malaysian politics, that is to say, lower income Malay voters. He understood that their challenge is primarily economic.

More importantly he knew how to communicate it. Makcik Kiah as a more effective imagery for class consciousness than AOC.

In this sense the current awakening, however short-lived it may turn out, has an air of authenticity that other attempts to galvanise Malay sentiment before did not. The Red-shirt rallies, Rani Kulup’s many trips to the police stations – they all missed the point. The consensus today stresses that the challenge Malays face is primarily of bread and butter. Religion and race may get them noticed but class consciousness is the prelude to more substantial solidarity. It is no coincidence that the Agung too has agreed to relinquish six months worth of his allowances.

The focus on the B40 as a social category furthermore makes the important point, lost to mainstream political discourse for decades, that not all Malays are struggling. The ire against Vivy Yusof, for all its unfairness, is at least sociologically accurate in this respect.

This to be sure is as much an indictment against Pakatan whose insistence on colour blindness translated to an unwillingness to feature poor Malays in its national vision. They replicate BN’s mistake when they also only speak of Malays as a monolithic category.

This is a strategic point. The Covid crisis occurred in the wake of a takeover by a backdoor government. But the covid crisis is also turning out to be a great leveller. The fact that we must all be confined at home for weeks is making life at a sparsely populated kampung a lot more appealing than a tight overpriced studio in Mont Kiara. Businesses are hurt and the crisis has claimed many elites (A white Prime minister and a Kelantanese Mufti to name just two). Where before only the b40 felt the unfairness of life, now the powerful must too.

Pakatan Harapan will critique the current government for not being liberal enough, dream of making LGE finance minister again and will treat the Rakyat with reruns of the Anwar and Mahathir grudge. But a post-NEP Malay world is being born and unless they too speak to poor Malays, they will not be a part of it.