By Yvonne Tan

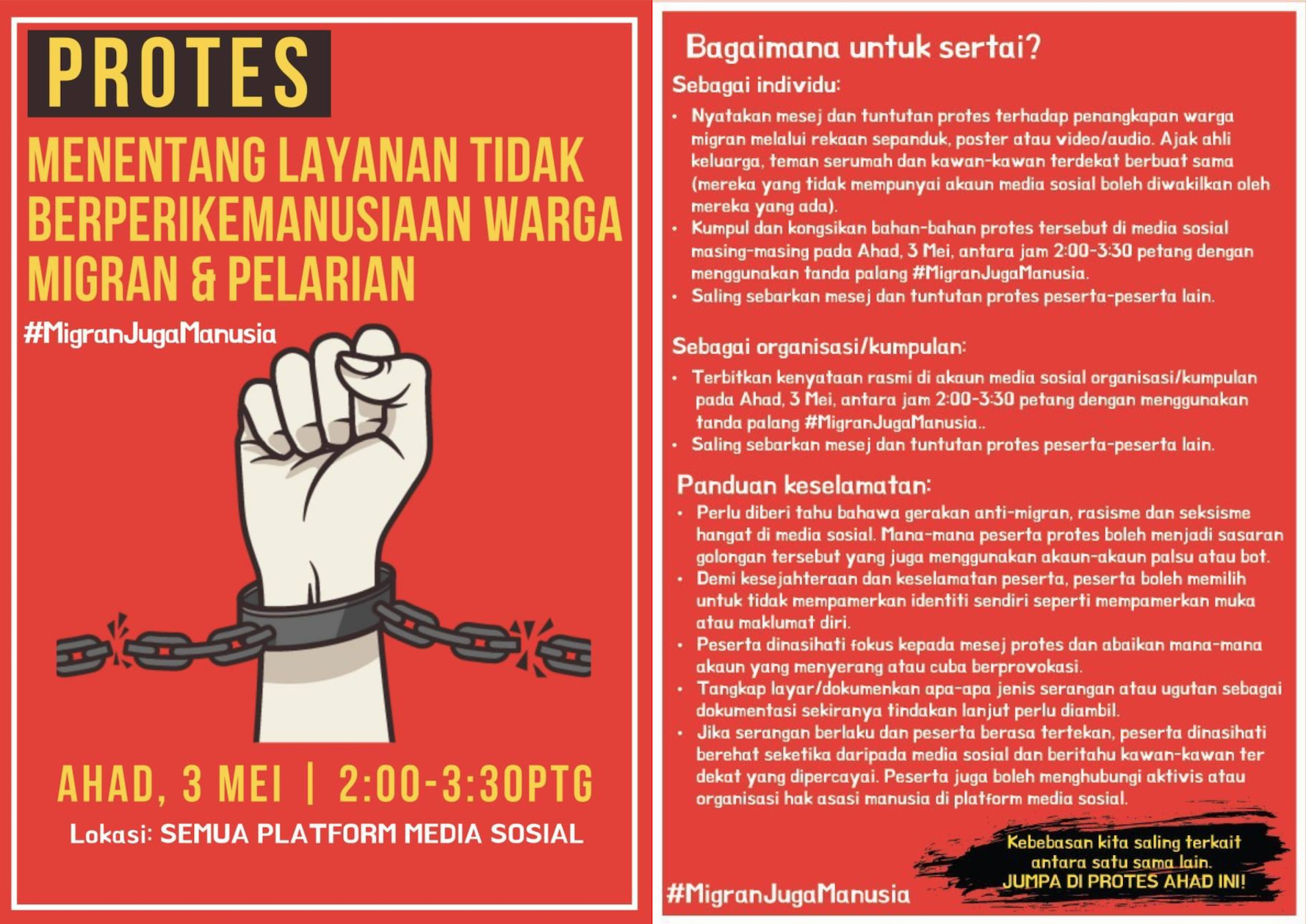

#MigranJugaManusia is a hashtag that began as an online protest against the mass arrests of migrants placed under Enhanced Movement Control Order. Utilising all social media platforms on 3 and 16 May, demanding:

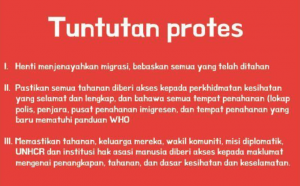

1) Stop mass arrests and to free those who have been detained

1) Stop mass arrests and to free those who have been detained

2) Ensuring those who have been detained to have access to health services and that detention centers comply with WHO guidelines

3) Ensure detainees, their families, community representatives, diplomatic missions, UNHCR and human rights institutions are granted access to information about the arrests, detainees, and health and safety policies.

- Met with immediate backlash, one of the popular responses was from The Patriots who criticised the movement for borrowing migration narratives from the US who hypocritically champion human rights despite their history of the slave trade and waging wars throughout the world until today. Emphasizing how the US might be a country of immigrants, Malaysia has always been a place for Malay civilisation:

“Ya, memang betul. US adalah negara imigran. Mereka datang berkelana dari Eropah, dan merampas negara milik Red India. Jadi dari pioneer yang terdiri dari WASP (white-anglosaxon protestant), Mafia Itali, sampailah ke bangsa kulit hitam semuanya adalah imigran.

Berbeza dengan Malaysia yang merupakan gabungan Semnangjung Tanah Melayu dan Borneo. Tapi kesuluruhan kepulauan Nusantara ni memang asalnya negeri Melayu. Penuh dengan kerajaan Melayu. Kalau bukan Melayu pun, ia tergolong dalam leluhur yang sama dalam kelompok Austronesia.”

— Betul Ke Negara Malaysia Ditubuhkan Oleh Imigran?

- Other reasons for blaming migrants have become popular where 4 Indonesians who tested positive for Covid-19 had run for their lives including for the rising number of cases in immigration detention centres. Meanwhile, netizens have discredited the online protest with the news of a Rohingya teen and his wife were charged with the murder of a 6-year-old girl done in front of a restaurant of a shopping mall in Ampang. Making the connection between ethnicity and wrongdoings have been a regular theme particularly throughout the last week as a reason for the inhumane treatment that is required.

- Another viral argument that came about include making the distinction from illegal, otherwise known as Pendatang Asing Tanpa Izin (PATI), from legal migrants. Ismail Sabri’s, the Minister of Defence, justification for the crackdown was that PATI have broken the law which jeopardised the majority of the people in the country. Hence, they are allowed to arrest and the freedom for them to reside here as a “human right” will not be taken into account by the government. Several have agreed with him stating that the process of obtaining legal permits also include medical checkups and expensive payments.

Criticising Eurocentrism and the hypocrisy of the West is a valid argument and we should look to our neighbours and history on how we can move forward on the issue. However, there needs to be equal criticism for the hypocrisy of our leaders as well. Najib Razak who has consistently taken a strong stance against the Rohingya genocide, led the solidarity rally to press the Myanmar government to stop its cruelties conveniently during election years. “We want to show Myanmar and tell Aung San Suu Kyi that enough is enough,” Najib had said. “I’m here today not as Najib Razak, but as a Malaysian and a Muslim. There is no assembly more honourable than that which is done for Islam.” Malaysia has previously set up the Gaza Emergency Fund in 1994 and offered refuge to Bosnian Muslims in the same year. Help was given with strong criticism against the West for their indifference to their plights with a similar rally being carried out where 30,000 Malaysians filled the Merdeka stadium. We have done it before, why not again?

But all these discussions reveal the limits of our discourse, missing the point where migrants are but the subaltern, voiceless. There is little attempt to understand the “mass” of migrants themselves apart from the fact they come from neighbouring countries “fleeing genocide”, “looking to improve their economic situation” and sometimes how well they have assimilated into Malaysia. Previously a family member of mine had a huge anti-immigrant sentiment until a few encounters which led her to speak to some. One of them included my neighbour’s maid. She would regularly come to the back of our house to speak to us, telling us of the ill-treatment she received, the debt she had accumulated from paying recruitment agencies, how she missed her son, extreme loneliness, counting the days her contract could end soon so that she could head back home to see him.

Another defining moment was regular trips to the photostat and stationery shop where she exchanged a few pleasantries with one of the foreign workers. Later on, someone in the shop came in and shouted at the worker for having accidentally photostated the wrong pages and became defensive of him for the treatment he received, telling the person off. As the protest attempts to emphasize humanity, so much of all we see is but a mass of people that is but an easy target to hold responsible for the dire state of a global pandemic.

First-hand accounts of having to navigate the structure of contractual transactions in the labour migration mechanism that can quickly turn into human trafficking and forced labour needs to be heard. Workers usually become entangled in a web of obligations towards their state, recruiters and employers in Malaysia when involving migration expenses, contracts and subsequent debt where the distinction between ‘legal’ and ‘illegal’ is but a fine line.

Mass arrests not only of locals but also immigrants is a highly worrying response in a time where prisons have become global epicenters for coronavirus. However, locals have access to lawyers, families’ representatives that migrants should have as well. Time and time again it has been repeated that coronavirus has shown that it could affect anyone rich or poor, and our response has been to shun “lower-skilled” immigrants while “higher-skilled” immigrants do not pose a problem.

Although social interactions are supposed to be minimised during these times, maybe try to attempt to hear out those who were never listened to as Spivak said, “for the ‘true’ subaltern group whose identity is its difference, there is no unrepresentable subaltern subject that can know and speak itself”.