by Yvonne Tan

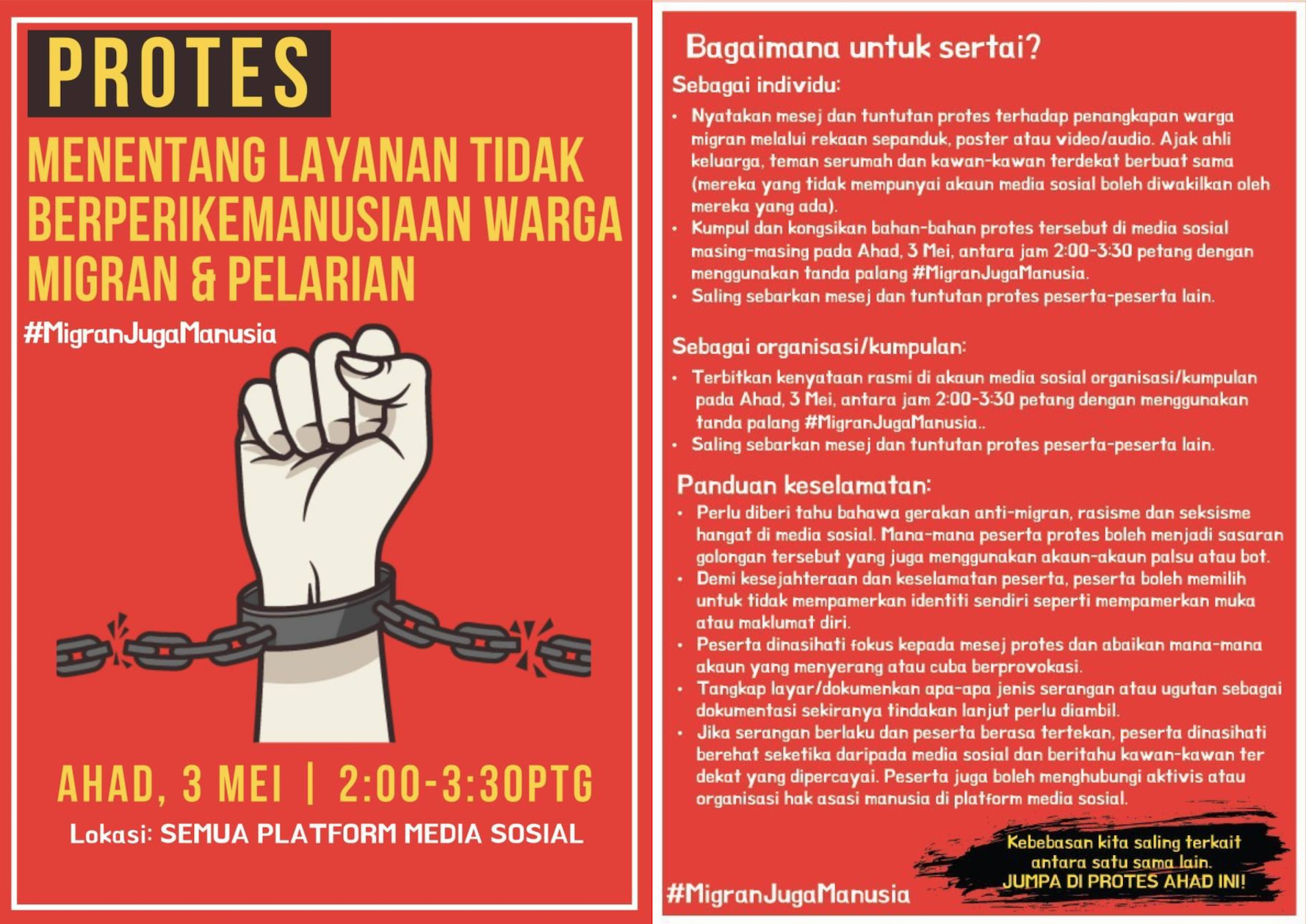

The month of June 2020 had sparked the George Floyd protests all over America before reigniting the #BlackLivesMatter movement throughout the world. As some protest what is happening in America, others protest the systemic racist practices in their own country such as in Indonesia with #PapuanLivesMatter while in Malaysia some discussion of the treatment of African students, in particular, Thomas Orhions Ewansiha’s death in police custody and #MigranJugaManusia.

As the identities of the officers were released, Tou Thao, an Asian American officer who had stood by as his colleague restrained and eventually killed George Floyd became another subject of discussion on anti-blackness within Asian communities. As the model minority myth is perpetuated about Asian American immigrants, it further justifies mistreatment of other minority groups including African and Latin American communities which is in itself an opportunity to touch on the once transnational dream of African-Asian solidarity.

As the identities of the officers were released, Tou Thao, an Asian American officer who had stood by as his colleague restrained and eventually killed George Floyd became another subject of discussion on anti-blackness within Asian communities. As the model minority myth is perpetuated about Asian American immigrants, it further justifies mistreatment of other minority groups including African and Latin American communities which is in itself an opportunity to touch on the once transnational dream of African-Asian solidarity.

One cannot speak about African-Asianism without mentioning the Bandung Conference [Konferensi Asia-Afrika] in 1995 and subsequently, the formation of the Non-Aligned Movement. At the height of the Cold War, postcolonial states were invited based on shared experience of Western imperialism to stand for anti-colonialism through transnational solidarity. Rachel Leow remarked how Bandung became “easy metonymy: Bandung the place, Bandung the spirit—Bandung the moment, Bandung the history. Anti-colonialism and transnational solidarity were all theatrical parts: Bandung was the diplomatic debut of newly decolonized peoples on a bipolar world stage, full of agency and vigour.” [1]

The “Bandung moment” was a spectacle with a global institutional space for decolonisation which was also, by and large, a foreign policy strategy. Jim Markham from the British colony Gold Coast, alongside Roo Watanabe, Menahem Bargil, Soerjokoesoemo Wijono, embarked on a research tour of then-Malaya, Indonesia and South Vietnam under the umbrella of the Asian Socialist Conference held in Yangon and Bombay during the mid-1950s as well. He had worried Britain of “Asian infiltration” wherein intelligence reports mentioned Markham’s research as “most impressive” with “acute understanding of wider problems” facing the Malayan Federation, as he warned how British and American firms expanded into cocoa plantations in Malaya to diversify away from the depressed global rubber market. [2]

Indian historian Vijay Prashad in Afro-Dalits of the Earth, Unite! (2000) proposes a polycultural approach to experiences in oppression instead of what he calls “epidermal determinism” which meant seeking solidarity on the basis of skin colour. When black slaves were emancipated in the Caribbean, North America and South Africa, Asian labour was brought in to replace and do the work of former slaves therefore continuing the racial strata of labour like in Trinidad and Guayana. Hence, such linkages were seen as important to Prashad for the struggle against universal racism. Part of growing Afro-Dalit scholarship alongside Ivan van Sertima, Runoko Rashidi and V. T. Rajshekar are among those who offer alternative approaches to the interconnections in African and Indian life. Rashidi told an Indian audience that he travels to India “to help establish a bond between the Black people of America and the Dalits, the Black Untouchables of India,” a tie that “will never be broken” and true enough the Black Lives Matter protests have spurred calls for India to end Dalit discrimination.

Grace Lee Boggs, who was mistaken by the FBI as an “Afro-Chinese”, personified her arguments against any approach that would focus singly on either race or class: “Whether the [March on Washington] movement proves transitory or develops into a broad and relatively permanent movement for Negro democratic and economic rights will depend upon whether it will develop a leadership which seeks its main support in the organized labour movement and whether the Negro masses in the labour movement are ready to enter into and actively support this general movement for Negro rights as a supplement to their economic and class activities within the unions themselves.” She and her husband, James Boggs, were deeply involved in the Black Power Movement and establishing multi-racial community institutions throughout Detroit, rooting politics in the struggle of black workers in the 1960s.

Grace Lee Boggs, who was mistaken by the FBI as an “Afro-Chinese”, personified her arguments against any approach that would focus singly on either race or class: “Whether the [March on Washington] movement proves transitory or develops into a broad and relatively permanent movement for Negro democratic and economic rights will depend upon whether it will develop a leadership which seeks its main support in the organized labour movement and whether the Negro masses in the labour movement are ready to enter into and actively support this general movement for Negro rights as a supplement to their economic and class activities within the unions themselves.” She and her husband, James Boggs, were deeply involved in the Black Power Movement and establishing multi-racial community institutions throughout Detroit, rooting politics in the struggle of black workers in the 1960s.

These are but some moments in a long history of transnationalism between Africans and Asians which emerged with the fall of Western empires. As national interests and growing Cold War tensions took precedence, African-Asian solidarity and other internationalist projects that explored decolonial possibilities did not take center stage as it had then.

Nevertheless, the beginning stages of the coronavirus pandemic saw a spike in Asian and eventually African discrimination, is a sober reminder that it is but an exacerbation of deeply rooted systemic racism that remains. As people across the world relate George Floyd’s death and police brutality against African Americans with the plight of Papuans, Aboriginals, Dalits, Rohingyas, Palestinians, migrant communities in Lebanon, Spain and of course Malaysia, the global protests are a watershed moment in carving out worldwide solidarity against the disciplinarian state that has used the excuse of the pandemic for too long to enact authoritarian measures.

Coupled with massive unemployment throughout the world and overall economic downturn, feeling the full effects of racial violence on top of inability to fight for justice in the workplace, people are forced to come to terms with their situation. Universal slogans adopted during the Black Lives Matter movement throughout the world include “All Cops are Bad” and “Silence is violence, Complacency is complicity.” Although this is but the beginning, just as how a pandemic affects the whole world, so does institutional racism coupled with repressive state apparatuses which have no opposition party against such. As much as health practitioners have spoken about how coronavirus does not discriminate across all races and classes, what has been taken into account instead is but how it would affect “the national community” or those most far removed from society while the marginal fall from the cracks. Taking lessons from African-Asian movement against colonialism, standing together globally against racism as a system that manifests in norms, institutions and policies is possible and needed in continuing the long fight to dismantle oppressive social hierarchies.

[1] Rachel Leow, ‘Asian Lessons in the Cold War Classroom: Trade Union Networks and the Multidirectional Pedagogies of the Cold War in Asia’, Journal of Social History vol 53 no. 2 (2019): 429–453, p. 430.

[2] Gerard McCann, ‘Where was the Afro in Afro-Asian Solidarity? Africa’s ‘Bandung Moment’ in 1950s Asia,’ Journal of World History, Volume 30, Numbers 1-2, June 2019, pp. 89-123

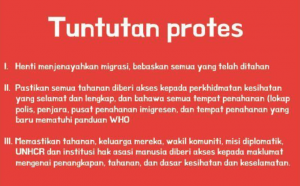

1) Stop mass arrests and to free those who have been detained

1) Stop mass arrests and to free those who have been detained