By Yvonne Tan

In the wake of the global coronavirus pandemic, several phrases have been repeated as ways to combat the spread of the virus. They include “stay home”/ “duduk rumah”, “wash your hands”/ “cuci tangan” and of course, “social distancing” / “penjarakkan sosial”. However, people all over the world have reacted with panic buying and stockpiling all sorts of non-durable goods in order to “prepare” for self-isolation and lockdowns, in which the easiest reasoning for the consumer phenomena is that pandemics shed light on how panic brings out the worst in people. Although panic buying did not necessarily take off within Malaysia, there is still a salient each-for-their-own behaviour that has materialised.

After countless arrests of MCO violators, it goes without saying the pandemic has provided an easy excuse for semi-authoritarian measures by many governments around the world. The Movement Control Order (MCO) refers to the Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases Order 2020 [PCID Order] under the Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases Act 1988 [PCID Act 1988] where the general penalty for a first offence is imprisonment of not more than 2 years or a fine.

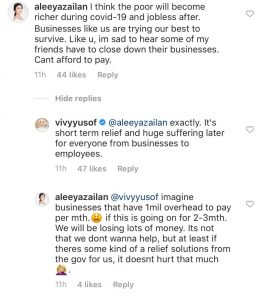

With the government imposing strict measures, what was most unexpected was the increase in policing by netizens throughout social media, proactively lodging reports against MCO violators. After videos of a preacher and his team who had been aiding the poor during MCO became viral, many parties had lodged police reports against him and hence were questioned by the police. Not to mention on 1 April 2020, the Selangor police spokesman, Ismail Muslim during a press conference stated between 18/3/2020 and 1/4/2020, the Selangor police had received 600 MCO-related reports. In another press conference given on 9 April 2020, 380 more MCO-related reports were received bringing the total to 980. If the numbers were true, there is a surge of reports lodged by the public which begs the question why is there a need to police one another?

As social media quickly became a new breeding ground for intolerance and xenophobia, rumours of Zafar Ahmad Abdul Ghani, who heads the Myanmar Ethnic Rohingya Human Rights Organisation Malaysia (Merhrom), had demanded citizenship was subsequently met with immense backlash. This coincided with authorities having denied entry to Rohingyas fleeing the genocide and persecution from the Myanmar government. Change.org had taken down the many online petitions started by the public to expel Rohingyas from Malaysia based on the false claims of their demands, one such petition garnering up to 250,000 signatures.

Despite all this, Zafar Ahmad Abdul Ghani denied ever making such a statement and Rohingya groups quickly apologised and distanced themselves from Zafar, urging that Malaysian authorities take action against him.

This all comes too convenient as neighbourhoods around Selayang Wholesale Market had tested positive for coronavirus and were quickly blamed amidst anti-Rohingya sentiments. Needless to say, it did not take long for authorities to conduct massive crackdowns on undocumented migrant workers. It is a time where every day we are forced to confront how limited resources are, be it the uncertainty of receiving one’s paycheck, restricted movements outside one’s home or access to goods that could quickly go into shortage overnight. With no vaccine in sight, it’s easy to prop up the disciplinary state when attempting to fully accept the reality of the pandemic. Not to mention, fall back on widely subscribed apocalyptic visions of the world such as fear of Islamic refugees arriving on boats, impending climate disaster, major economic downturn and so on [1].

As the nature of coronavirus transmission places responsibility on carriers of the virus who could unknowingly spread it and trigger a domino effect, hence social cooperation and compliance is consistently emphasized. The cause of the virus quickly becomes a game of blaming “irresponsibility” of specific persons, when really it is a luxury that those living paycheck to paycheck cannot afford. It has become a dangerous apolitical idea to blame your neighbour rather than our failing institutions and lack of social security to fall back on in times of need.

The reasoning for self-isolation throughout the pandemic was to ease the burden placed on the health system. However, it is important to reframe that the spread of the coronavirus is not completely in one’s hands but one can mitigate it as much as one possibly can. Rather than feeling the need to dominate every aspect of everyone’s life to comply with lockdown orders, we should seek alternatives done during this global pandemic such as Italy’s suspension of mortgage payments during lockdown to Taiwan’s stimulus coupons to encourage citizens to buy commodities to help affected businesses. As Arendt had noted individual isolation and loneliness are preconditions for totalitarian domination, “the “ice-cold reasoning” and the “mighty tentacle” of dialectics which “seizes you as in a vise” appears like a last support in a world where nobody is reliable and nothing can be relied upon.” [2]

Although this goes without saying this does not represent all Malaysians as the #KitaJagaKita initiative had also begun and flourished online among others. Hannah Alkaf stated it began with Twitter linking people who want to help with the people who need help. She mentioned “I hope ordinary people – people like us – realise how much of an impact they can make if they simply choose to help someone who needs it. I hope we come to a collective realisation that no society can call itself successful unless we work to raise everyone up, together. I hope we make it through this with kindness and compassion.” And maybe what we need is just that.

[1] Žižek, Slavoj. Pandemic! Covid-19 shakes the world. OR Books, 2020, p. 98.

[2] Arendt, Hannah. Origins of Totalitarianism. Harcourt Brace and Company, 1973, p. 478