by Yvonne Tan

EVERY so often some spaces offer a glimpse into the utopian Malaysia that is free of the race and religion strife which has become the backbone of our identity. Take Yasmin Ahmad’s films often described as a ‘dreamed’ Malaysia where such deep divisions have dissipated presenting a cinematic imagination of Malaysian multiculturalism [1]. Sepet was later discussed in parliament on whether the usage of Bahasa Rojak is appropriate and if the depiction of the love story was considered too liberal, which seems as something ludicrous now.

Sometimes we come across anecdotes that might have been recounted with an agenda, or not. Growing up across Methodist and Pentecostal churches, our pastors would always point to our “neighbours” who pray 5 times a day and not just on Sundays. Once a youth pastor told us once that he was bullied, he would run into the mosque and the Imam allowed him to stay there. After repeated times, with not much to do waiting for the bullies to run away, he asked the Imam to share with him some of his teachings where most of his knowledge of the Torah came from. The idea that another religion could make us more fervent in ours was usually repeated as a no-brainer.

On the other hand, every Friday, I would eat at a non-halal food court near a mosque, during Friday prayers. You could listen along to the sermons blasted on the megaphone, and they would regularly preach animatedly about living in harmony and respecting different faiths and races as well. These are some moments where it seems people do attempt to achieve the imagined melting pot community.

On the other hand, every Friday, I would eat at a non-halal food court near a mosque, during Friday prayers. You could listen along to the sermons blasted on the megaphone, and they would regularly preach animatedly about living in harmony and respecting different faiths and races as well. These are some moments where it seems people do attempt to achieve the imagined melting pot community.

Children have also used as a point of envisioning how a world where race and religion have yet to be learned. My Malay “BFF” when I was 12 told me her father said that Chinese people are “babi” because they love eating it and we both chuckled while I told her my father said Malay people are “babi” because they don’t know how to eat it. And of course, who could forget the “Malaysia Baru” phase where many declared that racial politics was finally overcome.

Of course, these may seem like mundane moments but achieving the reality of a truly multireligious and multiracial society should begin in our day-to-day spaces. With the pandemic, we have spent more time at home increasingly alienated from one another, witnessing an ongoing political crisis amidst the pandemic reminded by Muhyiddin Yassin’s announcements of movement control orders on national television, Najib’s 1MDB trials, and a string of controversies surrounding racism that offer a bleak reality of our current state.

Take news like Baling MP’s infamous “Gelap Tak Nampak, Pakailah Bedak” to Kasthuriraani Patto and calling into question Sarawak’s secular identity to “Sarawak Darul Hana”. Not to mention, the New Straits Times’ fiasco surrounding their op-ed “Help minimise threat to society” which speaks in support of the ban of the sale of liquor in convenience stores, featuring an image of a Malaysian Indian at a sundry shop.

It is as in a video by Projek Dialog “Apabila Agama Dipolitikkan”, presented by Uthaya Sankar, discusses how religion is usually used as a political toy when in fact understanding starts simply with normal people. The political arena of religion and also race can give a warped view of a Malaysia that is anything but religiously harmonious.

[yotuwp type=”videos” id=”Fy8_7DKZfqU” ]

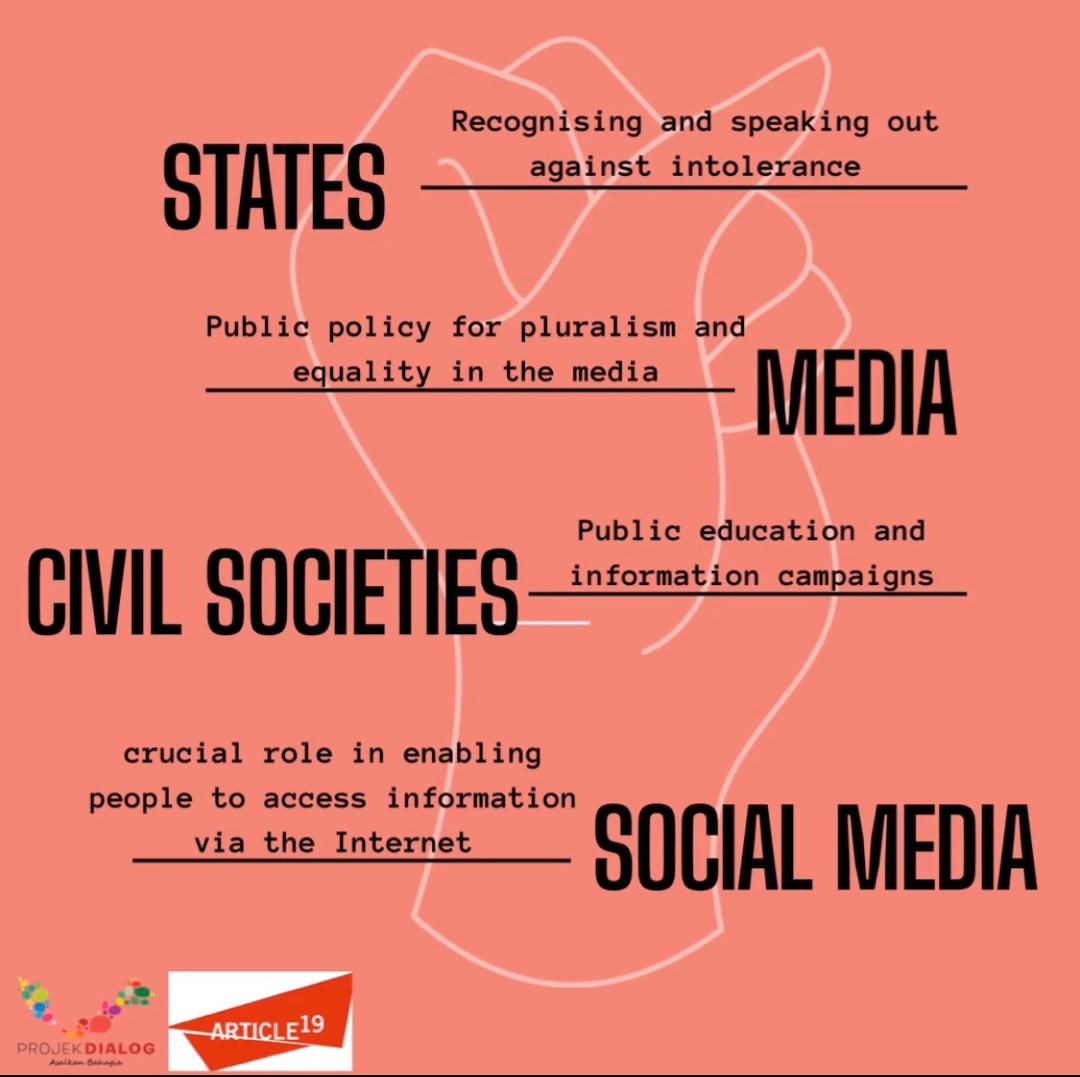

As the media becomes a more crucial medium to staying connected with the world in this time, reporting mostly on news centred on political and state affairs, it has presented us with a certain world view. We are all too familiar with the discourse of “post-truth” and “fake news” which has become a convenient catch-all term for anything online that does not support one’s perspective.

Baudrillard commented that media might not necessarily have an intention of deceiving, blurring or hiding the truth in mind, instead “rather than creating communication, it exhausts itself in the act of staging communication. Rather than producing meaning, it exhausts itself in the staging of meaning” (56). Hence, there is a tendency for the media to present reality is far from relevant to our current understanding of our lives.

Leading the “masses respond with ambivalence, to deterrence they respond with disaffection, or with an always enigmatic belief […] but one must guard against thinking that people believe in it.” Echoing Uthaya Sankar’s words from the video, “yang paling penting, tidak perlulah kita asyik bergantung pada ahli politik kerana pembinaan persefahaman dan ilmu haruslah mula dari diri kita sendiri.”

So, whenever you recount real-life experiences that may seem trivial and frivolous, they still offer important glimpses into everyday people undertaking the work to carve out a society that celebrates differences. Although it might be idealistic to see Malaysia as heading in the right direction especially when it comes to a touchy subject like race and religion, such instances can provide respite when swimming against the currents of our legacy of colonialism, racialised capitalism and politics.

Dr Wendy Yee who is a lecturer at University Malaya in a panel discussion hosted by Komuniti Muslim Universal (KMU) titled “The Role of State and Religious Leaders in Protecting Freedom of Religion and Belief” said aptly, “There are a lot of positive narratives out there in our daily lives which we can share and are loud enough to counter these negative narratives”.

References

[1] McKay, Benjamin (2011), ‘Auteur-ing Malaysia: Yasmin Ahmad and dreamed communities’, in M. A. Ingawanij and B. McKay (eds), Glimpses of Freedom: Independent Cinema in Southeast Asia, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Southeast Asia Program Publications, pp. 106–19.

We’re proud to announce that one of our PFK films, The House Without a Ground (Rumah Nda Bertanah) by Putri Purnama Sugua, which won the title of best director and storyline at our event, is nominated for the Short Fiction Category under the Calcutta International Short Film Festival 2020!

We’re proud to announce that one of our PFK films, The House Without a Ground (Rumah Nda Bertanah) by Putri Purnama Sugua, which won the title of best director and storyline at our event, is nominated for the Short Fiction Category under the Calcutta International Short Film Festival 2020! Kami dengan bangga mengumumkan bahawa salah satu filem PFK kami, Rumah Ndak Bertanah karya Putri Purnama Sugua, yang telah memenangi pengarah dan storyline terbaik di PFK kami, telah dinominasikan untuk ‘Fiksyen Pendek Terbaik’ di Festival Filem Pendek Antarabangsa di Calcutta!

Kami dengan bangga mengumumkan bahawa salah satu filem PFK kami, Rumah Ndak Bertanah karya Putri Purnama Sugua, yang telah memenangi pengarah dan storyline terbaik di PFK kami, telah dinominasikan untuk ‘Fiksyen Pendek Terbaik’ di Festival Filem Pendek Antarabangsa di Calcutta!

PEN, untuk makluman anda adalah sebuah kelab sejagat yang menghimpunkan pengarang, editor, pemilik kedai buku, penerjemah dan pengamal teater-filem (khusus dramaturgis) yang berpangkalan di London. Sejak kelahirannya, PEN memberikan tumpuan kepada kerja-kerja membela dan melindungi pengarang dari tekanan dan kezaliman pihak berkuasa. PEN juga meraikan apa sahaja bahasa yang dipilih oleh pengarang dalam karyanya – tanpa prejudis – asalkan karya itu tujuannya demi kemanusiaan.

PEN, untuk makluman anda adalah sebuah kelab sejagat yang menghimpunkan pengarang, editor, pemilik kedai buku, penerjemah dan pengamal teater-filem (khusus dramaturgis) yang berpangkalan di London. Sejak kelahirannya, PEN memberikan tumpuan kepada kerja-kerja membela dan melindungi pengarang dari tekanan dan kezaliman pihak berkuasa. PEN juga meraikan apa sahaja bahasa yang dipilih oleh pengarang dalam karyanya – tanpa prejudis – asalkan karya itu tujuannya demi kemanusiaan. Seorang Nazi, yang hadir dalam delegasi dari Jerman telah menghalang Ernst Toller, seorang penulis teater Yahudi-Jerman yang hidup dalam buangan daripada berucap mengutuk Nazisme (dan tindakan membakar buku). Satu suara yang solid, kuat, formidable dan meyakinkan telah terbit dari persidangan itu. Para pengarang bersetuju untuk menolak usul Jerman mendokong kebebasan bersuara penuh (justeru menerima Nazisme) lantas kembali memihak kepada prinsip-prinsip yang telah mereka mandatkan. Pasukan dari Jerman marah lantas membantah, langsung bertindak untuk keluar dari Persidangan. Mereka malah memilih untuk keluar daripada PEN, sehinggalah selepas Perang Dunia Kedua.

Seorang Nazi, yang hadir dalam delegasi dari Jerman telah menghalang Ernst Toller, seorang penulis teater Yahudi-Jerman yang hidup dalam buangan daripada berucap mengutuk Nazisme (dan tindakan membakar buku). Satu suara yang solid, kuat, formidable dan meyakinkan telah terbit dari persidangan itu. Para pengarang bersetuju untuk menolak usul Jerman mendokong kebebasan bersuara penuh (justeru menerima Nazisme) lantas kembali memihak kepada prinsip-prinsip yang telah mereka mandatkan. Pasukan dari Jerman marah lantas membantah, langsung bertindak untuk keluar dari Persidangan. Mereka malah memilih untuk keluar daripada PEN, sehinggalah selepas Perang Dunia Kedua. Apakah bentuk kebencian yang ditolak dalam karya sastera?

Apakah bentuk kebencian yang ditolak dalam karya sastera?

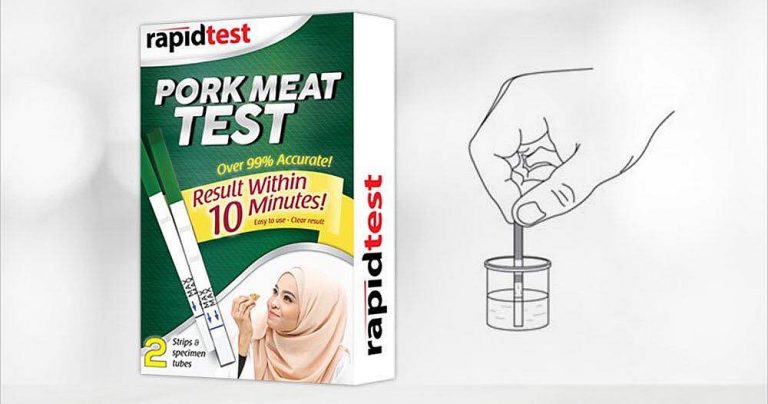

Iftitah Solutions (M) Sdn Bhd, owner of the brand Rapidtest released a product in 2019 called

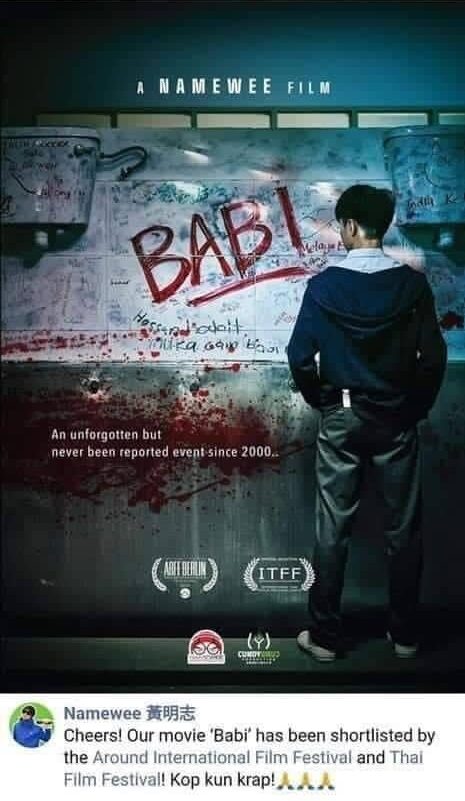

Iftitah Solutions (M) Sdn Bhd, owner of the brand Rapidtest released a product in 2019 called  Namewee, who is no stranger to controversies since his parody of Negarakuku, is once again at the center of public attention for his film conspicuously named Babi. After Namewee celebrated his international nominations at the Open World Toronto Film Festival, Around International Film Festival and Thai Film Festival the Perikatan Nasional Youth lodged a report specifically against the film’s poster. It featured a vandalized wall of a toilet with words like “Cina babi” other racial slurs such as “Melayu B-“ and “Indian K-“, not revealing the full derogatory slur of the other races. Namewee claimed the film was banned in Malaysia and is based on an alleged race-war that started innocently in a Malaysian high school in 2000 and covered up.

Namewee, who is no stranger to controversies since his parody of Negarakuku, is once again at the center of public attention for his film conspicuously named Babi. After Namewee celebrated his international nominations at the Open World Toronto Film Festival, Around International Film Festival and Thai Film Festival the Perikatan Nasional Youth lodged a report specifically against the film’s poster. It featured a vandalized wall of a toilet with words like “Cina babi” other racial slurs such as “Melayu B-“ and “Indian K-“, not revealing the full derogatory slur of the other races. Namewee claimed the film was banned in Malaysia and is based on an alleged race-war that started innocently in a Malaysian high school in 2000 and covered up.

Unions in Malaysia are categorised according to the private sector, public sector, employers’ unions and unions in statutory bodies and local authorities. Within the private sector, there can be national unions, that tries to cover workers of the same occupation, and in-house/enterprise unions for workers with the same employer [1]. Malaysian Trades Union Congress (MTUC) was established in 1949 to encompass unions from both public and private sector, of various occupations and trades, however, it does not qualify as a union, rather it is registered as a society.

Unions in Malaysia are categorised according to the private sector, public sector, employers’ unions and unions in statutory bodies and local authorities. Within the private sector, there can be national unions, that tries to cover workers of the same occupation, and in-house/enterprise unions for workers with the same employer [1]. Malaysian Trades Union Congress (MTUC) was established in 1949 to encompass unions from both public and private sector, of various occupations and trades, however, it does not qualify as a union, rather it is registered as a society. Despite anti-union tactics employed by companies, there are many instances till today that unionising works even in an environment that is highly unfavourable to organising. Collective bargaining is usually favoured, and if negotiations continue to remain in a deadlock the issue is taken to the Industrial Court. The

Despite anti-union tactics employed by companies, there are many instances till today that unionising works even in an environment that is highly unfavourable to organising. Collective bargaining is usually favoured, and if negotiations continue to remain in a deadlock the issue is taken to the Industrial Court. The

Abortion services are available in the private sector that is, of course, clandestine about but comes with high costs. Due to socio-economic reasons,

Abortion services are available in the private sector that is, of course, clandestine about but comes with high costs. Due to socio-economic reasons,