by Low Tse Yenn

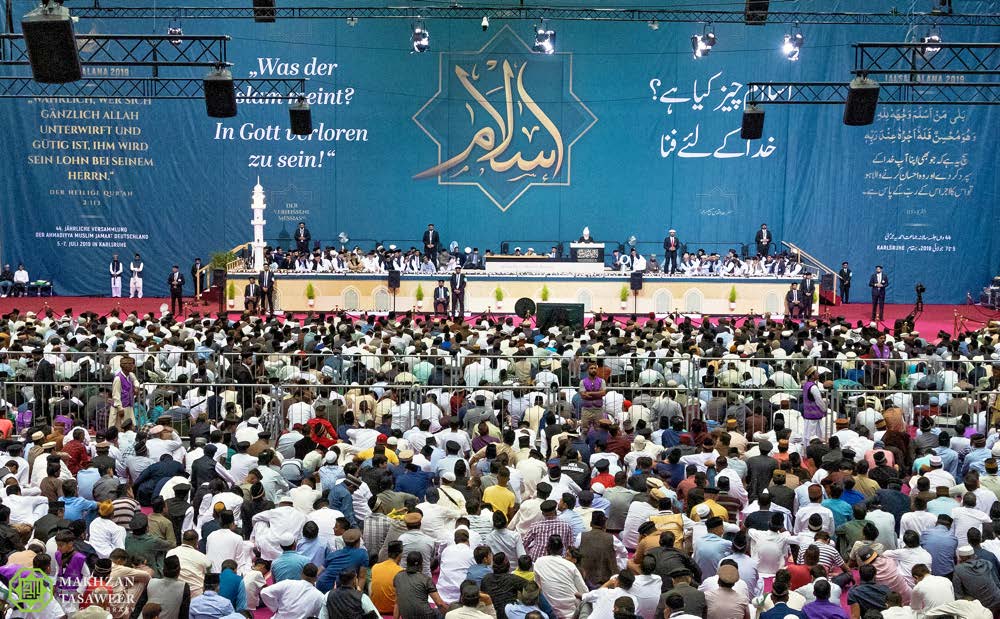

Every year, Ahmadiyya Muslims around the world await the Jalsa Salana – a formal annual religious convention, which allows attendees and spectators alike to explore and expand upon their faith. The convection spans across 3 days, always beginning on a Friday after Friday prayers and coming to a close on a Sunday. While many countries often host their own national Jalsa, the Jalsa Salana UK is an international spectacle – drawing the eyes from Ahmadiyya Muslims worldwide as it is broadcasted on Muslim Television Ahmadiyya (MTA).

The Ahmadiyya Muslim community, who otherwise refer to themselves as the Jama’at, refers to the Islamic movement which exalts Mirza Ghulan Ahmad, a religious leader from Punjab, British India who rose to prominence in the 19th century, as the Messiah and Mahdi – the metaphorical second coming of Christ. Believers of this branch of Islam are referred to as Ahmadi Muslims – named after the prophet Muhammad’s alternative name, Ahmad.

This year marks the return of Jalsa Salana UK after its 2-year gap due to the Covid-19 pandemic., though accompanied by various health and safety measures. It was held on the 5th to 8th of August at the Hadeeqatul Mahdi, hosting a total of 8,887 invitees – 6,709 and 2,168 men and women respectively; though this pales in comparison to the usual 35,000 Ahmadis it usually draws from around the world.

This year marks the return of Jalsa Salana UK after its 2-year gap due to the Covid-19 pandemic., though accompanied by various health and safety measures. It was held on the 5th to 8th of August at the Hadeeqatul Mahdi, hosting a total of 8,887 invitees – 6,709 and 2,168 men and women respectively; though this pales in comparison to the usual 35,000 Ahmadis it usually draws from around the world.

The invitees were chosen by ballot while 4,000 Muslims who were unable to attend gathered virtually at 40 mosques and centers across the UK to watch the Jalsa. This stands testament to how Jalsa Salana is the largest annual Islamic convention in the UK, having run for over 50 years and organized every year by the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community (AMC)

The invitees were chosen by ballot while 4,000 Muslims who were unable to attend gathered virtually at 40 mosques and centers across the UK to watch the Jalsa. This stands testament to how Jalsa Salana is the largest annual Islamic convention in the UK, having run for over 50 years and organized every year by the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community (AMC)

On each day, an address was given by the global Islamic Caliph of the AMC – Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad (aba), otherwise called Huzur by Ahmaddis. The Jalsa began with an inauguration, held at the Jalsa Gah – the stage and seating area where Huzur and attendees congregate. Here, Huzur affirms that while this year’s Jalsa might be small in size, it was nevertheless held to quench the spiritual thirst of the people and to allow those chosen to serve the guests of the Promised Messiah.

Through these addresses, Huzur commends the Jama’at’s great work – speaking of missionaries worldwide and testimonies from new believers. He speaks of the fruits of their labor, in the 211 mosques built, in the many new converts, in the numerous people reached through their publications and translations, and how connections between past and lost converts have been strengthened and rebuilt. He also details the good work done beyond the religious realm – speaking of their humanitarian and medical efforts in emergency situations worldwide.

Through these addresses, Huzur commends the Jama’at’s great work – speaking of missionaries worldwide and testimonies from new believers. He speaks of the fruits of their labor, in the 211 mosques built, in the many new converts, in the numerous people reached through their publications and translations, and how connections between past and lost converts have been strengthened and rebuilt. He also details the good work done beyond the religious realm – speaking of their humanitarian and medical efforts in emergency situations worldwide.

Yet, at the core of his addresses are spiritually riveting sermons – ones that expands upon the core teachings of Islam. In his address on the last day, he builds upon sermons from prior Jalsas, speaking of the rights of others and how Ahmadis should act in propriety of them. He speaks on the rights of friends, the sick, the orphans, oaths, and others during the war – reiterating the significance of duty, righteousness, and intention. In the end, he closes the address as usual and ends the convention with a silent prayer.

Featured throughout the convention are interviews and testimonies by the invitees, staff, and volunteers. Here, they recount the significance of the Jalsa and the very visceral experience which accompanies it. Often, they speak of Huzur as an awe-inspiring and close figure – one they hold a deeply personal relationship with.

The Huzur commands a powerful presence, one which invokes in Ahmaddi Muslims a spiritual and emotional experience. Beyond the teachings and sermons the Jalsa will impart them, the Jalsa presents Ahmaddi Muslims the privilege of being in his presence and the chance to serve and hopefully meet him.

The Huzur commands a powerful presence, one which invokes in Ahmaddi Muslims a spiritual and emotional experience. Beyond the teachings and sermons the Jalsa will impart them, the Jalsa presents Ahmaddi Muslims the privilege of being in his presence and the chance to serve and hopefully meet him.

This year Jalsa’s stands as a feat in and of itself – a large convention held during one of the most vulnerable and dangerous periods in history. According to Huzur, the organizers had initially believed that the Jalsa would not be held due to the current Covid-19 conditions.

This assumption would continue to spill over to affect the preparations of the Jalsa – leading Huzur to believe that the organizers were not doing it with full conviction. Worrying that the half-hearted conditions of the organizers would affect the volunteers and workers, Huzur had expressed his concern to them – jolting them into a greater sense of urgency despite delays in preparation.

Huzur recognizes the workers and volunteers as the true driving force of the Jalsa. He mentioned that while many were disappointed that they were not chosen to serve, those that were chosen had fulfilled their duty to their utmost conviction and would be thoroughly rewarded by Allah. Though faced with weather setbacks such as heavy rain, the volunteers came together to dirty their hands with great spirit in order to help the many struggling cars in the muddied parking lots throughout the tiring weekend – showcasing a great display of their conviction.

There have been concerted

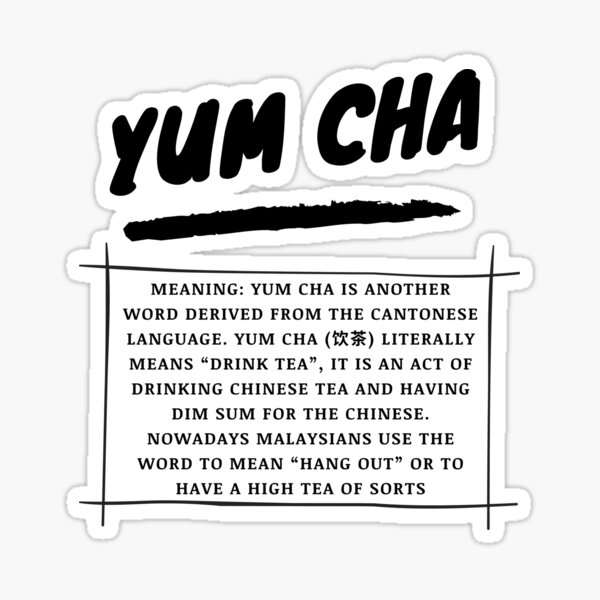

There have been concerted  Hence, there is a need to reframe languages thought of as “dialects” within Malaysia that reflect the many varieties of Malaysian Chinese identities. “Dialects” typically have a reputation as a language that people default to in order to fully express their anger. The mixing of languages in Malaysia is typically celebrated for multiculturalism and achievement of the 1Malaysia agenda but the discourse on individual Malaysian Chinese and Indian identities really only begins and ends with if you are banana or coconut. Rarely do we assess the internal dynamics and identities of being Malaysian Chinese beyond defending its right to exist. It is as Li Zishu 黎紫书 asks: “In our generation, we have no homeland nor cultural origin [in China]. We grow up here [Malaysia]. How do we face this place? How do we learn about ourselves?” [3]

Hence, there is a need to reframe languages thought of as “dialects” within Malaysia that reflect the many varieties of Malaysian Chinese identities. “Dialects” typically have a reputation as a language that people default to in order to fully express their anger. The mixing of languages in Malaysia is typically celebrated for multiculturalism and achievement of the 1Malaysia agenda but the discourse on individual Malaysian Chinese and Indian identities really only begins and ends with if you are banana or coconut. Rarely do we assess the internal dynamics and identities of being Malaysian Chinese beyond defending its right to exist. It is as Li Zishu 黎紫书 asks: “In our generation, we have no homeland nor cultural origin [in China]. We grow up here [Malaysia]. How do we face this place? How do we learn about ourselves?” [3]

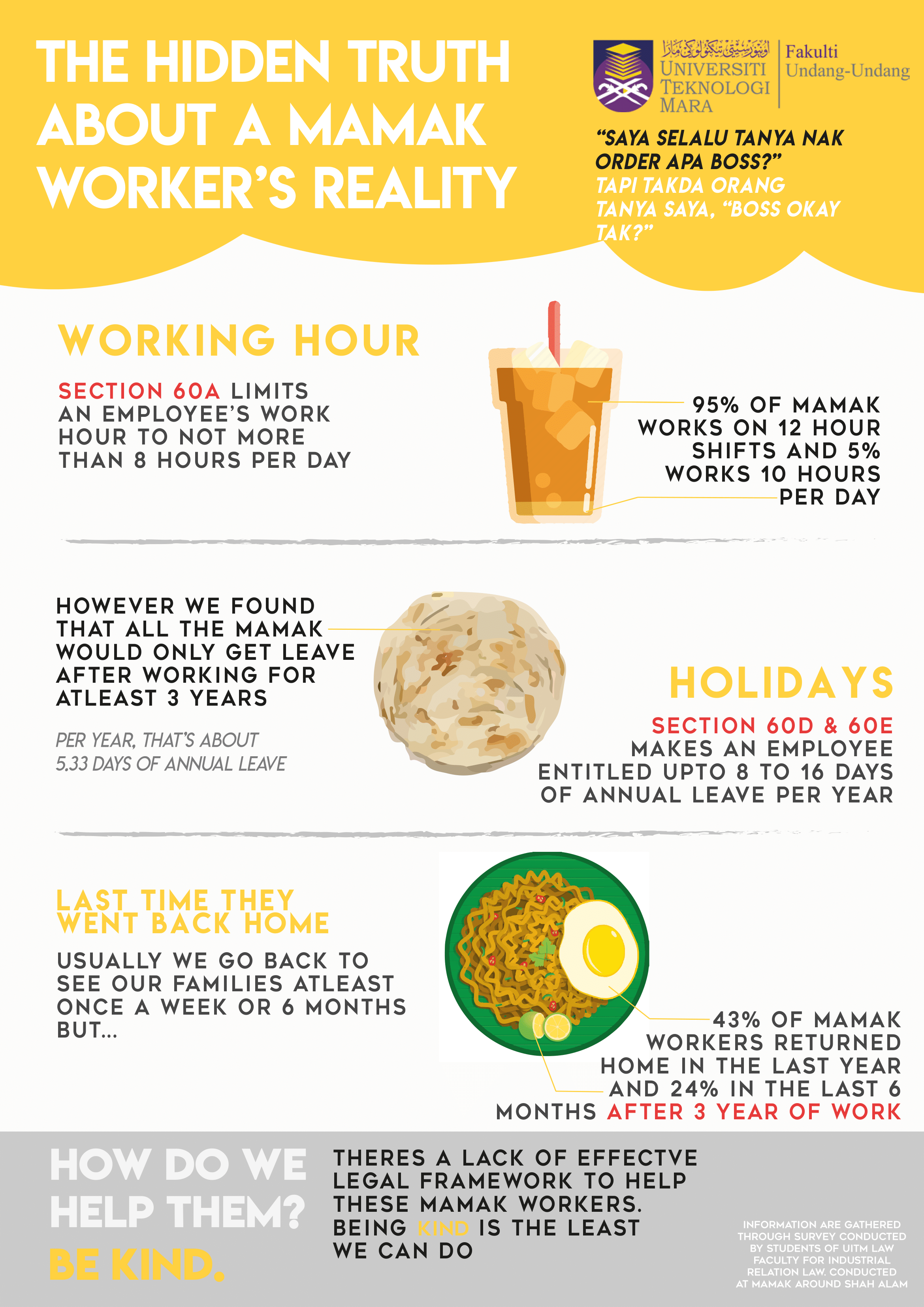

A UiTM study for a course assignment in January 2021 had conducted

A UiTM study for a course assignment in January 2021 had conducted  And it has only gotten worse with the new wave of raids on migrants following MCO 3.0 where videos of

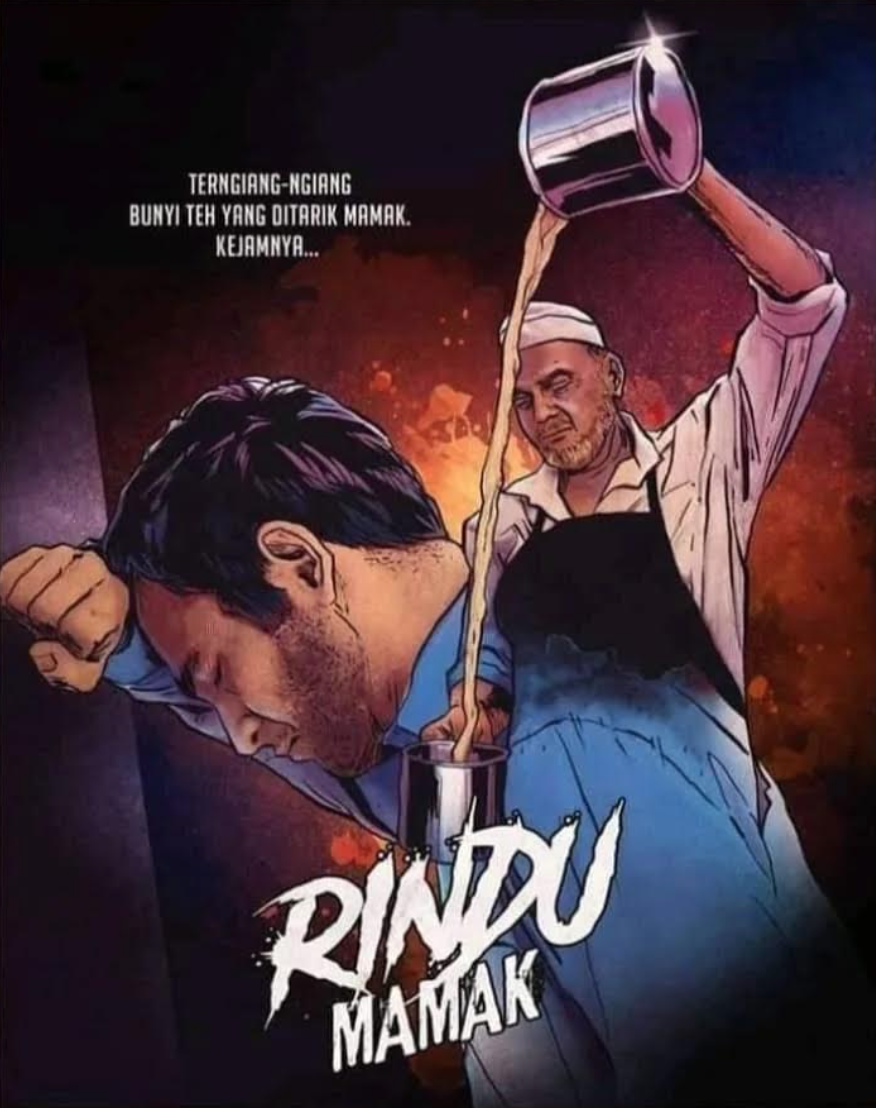

And it has only gotten worse with the new wave of raids on migrants following MCO 3.0 where videos of  Hence, let us reassess the identity of the mamak which has become the exemplar of food as both a point of national unity and division. Lauded as democratic and popular spaces for multiculturalism when turning a blind eye to the plight of the migrant workers operating such stalls, the pandemic has amplified this divide. As memes of missing mamak food proliferate while another mass immigration crackdown is carried out, it is a dichotomy that we should reconcile with. Malaysian food continues to be a point of national pride for most of us and as empathy can be a starting point, there is a need to demand for change to the precarious systems that will eventually result in the end of such establishments with

Hence, let us reassess the identity of the mamak which has become the exemplar of food as both a point of national unity and division. Lauded as democratic and popular spaces for multiculturalism when turning a blind eye to the plight of the migrant workers operating such stalls, the pandemic has amplified this divide. As memes of missing mamak food proliferate while another mass immigration crackdown is carried out, it is a dichotomy that we should reconcile with. Malaysian food continues to be a point of national pride for most of us and as empathy can be a starting point, there is a need to demand for change to the precarious systems that will eventually result in the end of such establishments with

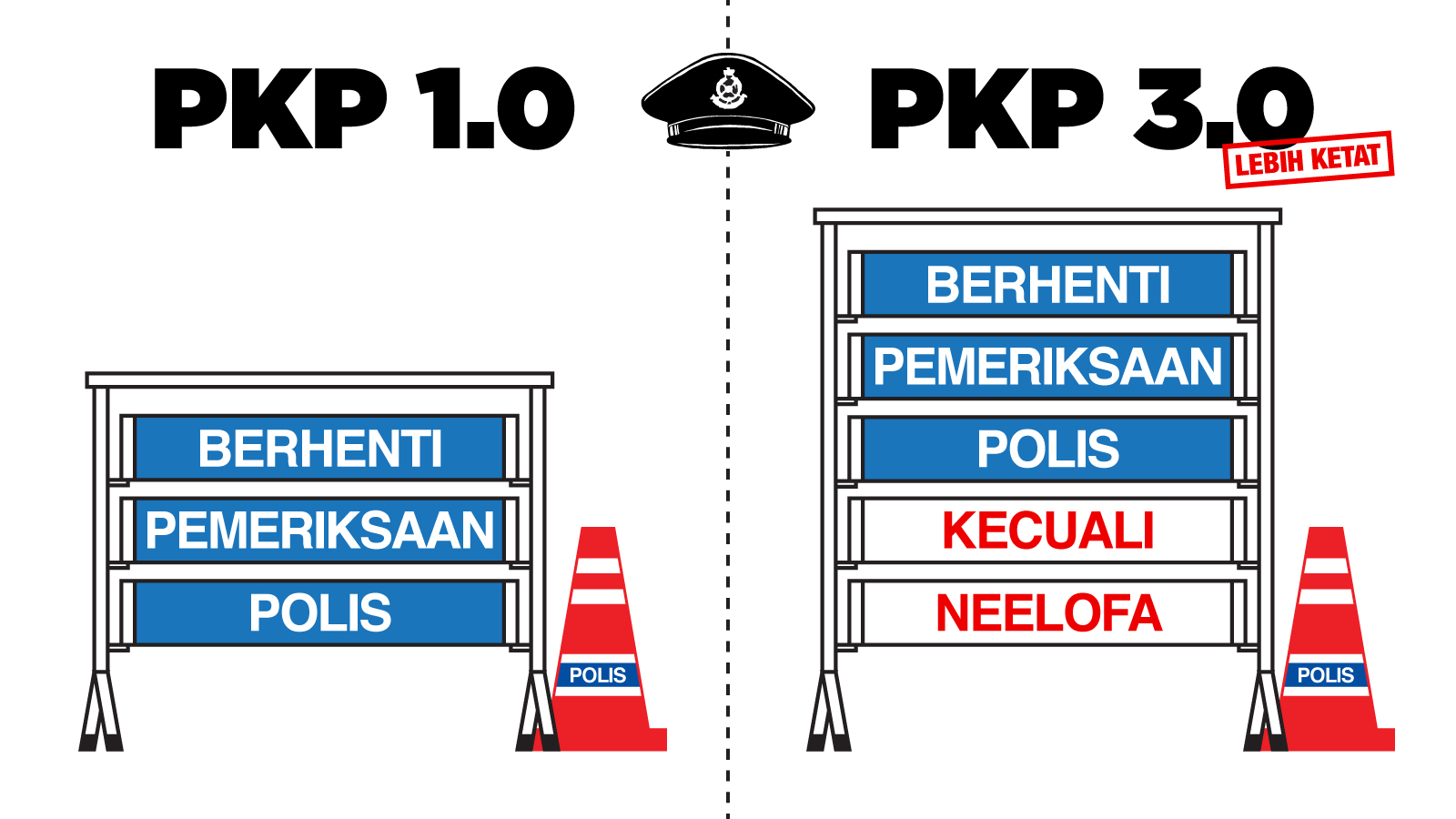

During the ongoing outrage directed against Neelofa, a small tide turned a little into questioning the police on a separate matter. In stark contrast within the span of almost a month, there have been two deaths in police custody at Gombak district police headquarters (IPD). Security guard Sivabalan Subramaniam died within an hour in police custody while cow milk trader A. Ganapathy succumbed to his injuries caused by police brutality after spending over a month at the Selayang Hospital’s intensive care unit. The

During the ongoing outrage directed against Neelofa, a small tide turned a little into questioning the police on a separate matter. In stark contrast within the span of almost a month, there have been two deaths in police custody at Gombak district police headquarters (IPD). Security guard Sivabalan Subramaniam died within an hour in police custody while cow milk trader A. Ganapathy succumbed to his injuries caused by police brutality after spending over a month at the Selayang Hospital’s intensive care unit. The

24 April 2021, Fahmi Reza lifted up the

24 April 2021, Fahmi Reza lifted up the

This brings us to Malaysia. Myanmar people continues to be viewed through the lens of not only as “migrant workers” but Pendatang Asing Tanpa Izin. The rhetoric of PATI spread like wildfire during COVID-19, implying there was immense trust in our systems to ensure no one was wrongly charged and belief that they were spreading the government’s resources thin. This is despite having little to no transparency and the immigration department’s long history of corruption and abuses, on top of its links to human trafficking. When the deportation of the 1,086 Myanmar nationals went through despite the Kuala Lumpur High Court order, while there were revived #MigranJugaManusia online protests, there was also a strong sentiment that they should simply be “sent back to where they came from”.

This brings us to Malaysia. Myanmar people continues to be viewed through the lens of not only as “migrant workers” but Pendatang Asing Tanpa Izin. The rhetoric of PATI spread like wildfire during COVID-19, implying there was immense trust in our systems to ensure no one was wrongly charged and belief that they were spreading the government’s resources thin. This is despite having little to no transparency and the immigration department’s long history of corruption and abuses, on top of its links to human trafficking. When the deportation of the 1,086 Myanmar nationals went through despite the Kuala Lumpur High Court order, while there were revived #MigranJugaManusia online protests, there was also a strong sentiment that they should simply be “sent back to where they came from”. Out of fear, Myanmar people have not publicly protested en masse in Malaysia unlike its diaspora in Thailand, Australia, Taiwan, Japan and so on. However, one high profile act of resistance was by Hein Htet Aung, from Selangor FC II. He celebrated his goal win with the three-finger salute. He was then suspended for a game, with netizens supporting the idea of “not bringing over one’s politics to another’s soil”. Echoing the same fear of importing instability, it is only fitting to say, “it must be a fragile system if it can be brought down by a few berries”.

Out of fear, Myanmar people have not publicly protested en masse in Malaysia unlike its diaspora in Thailand, Australia, Taiwan, Japan and so on. However, one high profile act of resistance was by Hein Htet Aung, from Selangor FC II. He celebrated his goal win with the three-finger salute. He was then suspended for a game, with netizens supporting the idea of “not bringing over one’s politics to another’s soil”. Echoing the same fear of importing instability, it is only fitting to say, “it must be a fragile system if it can be brought down by a few berries”. The

The  How is it done? The policy of the debate or the idea of Mubadalah begins by emphasizing the monotheism of Islam, the basis and core of the faith which is completely anti-patriarchal. The author argues that the Qur’an should not be misunderstood at all and that Prophet Muhammad came to humanize the ignorant Arabs, and to return the status of humanity to women. Before the arrival of the Prophet, unfortunately, women were not considered human. Women in the age of ignorance were oppressed at will. They are slaves to lust, women are given gifts, debt security, hostages, to be raped, married or divorced, to the point of being buried alive simply because of their gender.

How is it done? The policy of the debate or the idea of Mubadalah begins by emphasizing the monotheism of Islam, the basis and core of the faith which is completely anti-patriarchal. The author argues that the Qur’an should not be misunderstood at all and that Prophet Muhammad came to humanize the ignorant Arabs, and to return the status of humanity to women. Before the arrival of the Prophet, unfortunately, women were not considered human. Women in the age of ignorance were oppressed at will. They are slaves to lust, women are given gifts, debt security, hostages, to be raped, married or divorced, to the point of being buried alive simply because of their gender. Therefore, this book not only re-examines the gender text as a whole, but also ranks and establishes women as equal to men. This is done so that the claim that women are the source of slander is refuted and no longer accepted recklessly. The issues of nusyuz, polygamy, iddah and child-rearing are given a great context so that they are not isolated in just one space. It seeks to liberate women where the issue of women’s prominence as scholars are given attention. This includes resolutely challenging the position of women as the prayer imam. Then, the hadith ‘it will not be happy for the people to leave the affairs of their leadership to a woman’ as an example is seen not on the issue of gender but rather, is actually a prophecy of the Prophet Muhammad on the fall of the Persian empire at the hands of a woman. Reading this perspective provides us with logic for today’s world where women’s leadership is far more successful than men’s, as highlighted by Chancellor Merkel in Germany or the Prime Minister of New Zealand, Jacinda Adern.

Therefore, this book not only re-examines the gender text as a whole, but also ranks and establishes women as equal to men. This is done so that the claim that women are the source of slander is refuted and no longer accepted recklessly. The issues of nusyuz, polygamy, iddah and child-rearing are given a great context so that they are not isolated in just one space. It seeks to liberate women where the issue of women’s prominence as scholars are given attention. This includes resolutely challenging the position of women as the prayer imam. Then, the hadith ‘it will not be happy for the people to leave the affairs of their leadership to a woman’ as an example is seen not on the issue of gender but rather, is actually a prophecy of the Prophet Muhammad on the fall of the Persian empire at the hands of a woman. Reading this perspective provides us with logic for today’s world where women’s leadership is far more successful than men’s, as highlighted by Chancellor Merkel in Germany or the Prime Minister of New Zealand, Jacinda Adern.

How do we put an end to this harmful discourse of “Melayu Malas”, “Cina tamak/tipu” and “India mabuk minum todi”? One way is to point to today’s system that has continued to uphold these problems today. Defaulting these stereotypes of character lays the fault in the victims, not the systemic problems at hand. Jagat (2015) is a film that captures these problems extraordinarily well behind the stereotypes associated with the Indian community. Bala is a relapsed drug addict, Dorai/Mexico is the reluctant gang member and Maniam a former estate worker that are father figures in Appoy’s life. With not much hope from the education system nor his family unit, he finds refuge in a gang and a life of crime.

How do we put an end to this harmful discourse of “Melayu Malas”, “Cina tamak/tipu” and “India mabuk minum todi”? One way is to point to today’s system that has continued to uphold these problems today. Defaulting these stereotypes of character lays the fault in the victims, not the systemic problems at hand. Jagat (2015) is a film that captures these problems extraordinarily well behind the stereotypes associated with the Indian community. Bala is a relapsed drug addict, Dorai/Mexico is the reluctant gang member and Maniam a former estate worker that are father figures in Appoy’s life. With not much hope from the education system nor his family unit, he finds refuge in a gang and a life of crime.

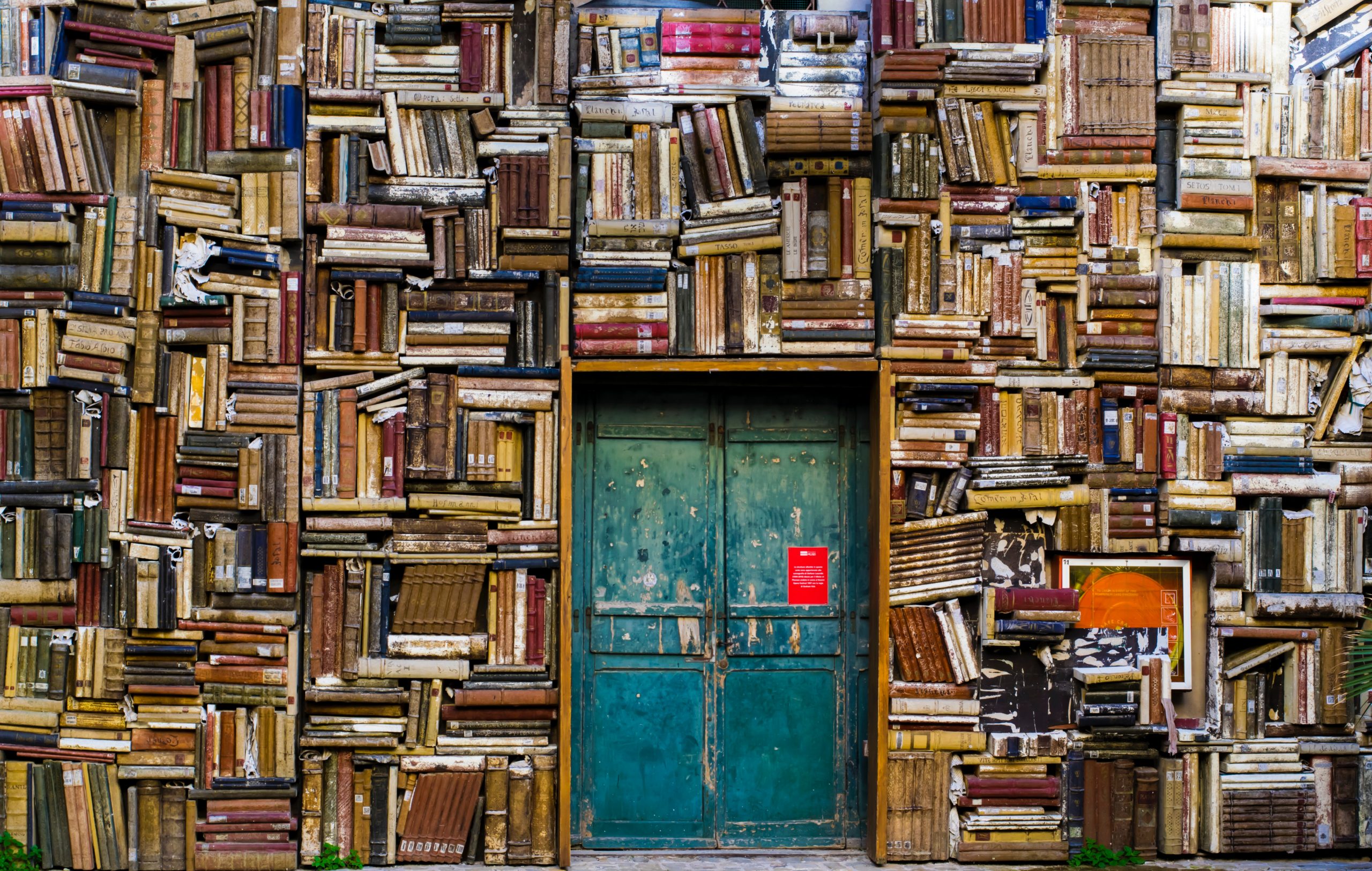

For your information, PEN is a universal club that brings together London-based authors, editors, bookstore owners, translators and theatre-film practitioners (specifically dramaturgists). Since its inception, PEN has focused on the work of defending and protecting authors from the pressure and tyranny of the authorities. PEN also celebrates whatever language the author chooses in his work – without prejudice – as long as the work is intended for the sake of humanity.

For your information, PEN is a universal club that brings together London-based authors, editors, bookstore owners, translators and theatre-film practitioners (specifically dramaturgists). Since its inception, PEN has focused on the work of defending and protecting authors from the pressure and tyranny of the authorities. PEN also celebrates whatever language the author chooses in his work – without prejudice – as long as the work is intended for the sake of humanity. This is because literary works should be given freedom in their scope to express honest criticism of any element of human culture including religion, politics and history. An author, for example, must be free to question religious practices that may be unfair to its adherents. An author must also be allowed to fully provoke criticism and question harmful political actions. For example, the discrimination policy driven by the Nazi Party led to the deaths of many innocent people as a result of the war. Authors are also allowed to freely rediscover history in their literary works.

This is because literary works should be given freedom in their scope to express honest criticism of any element of human culture including religion, politics and history. An author, for example, must be free to question religious practices that may be unfair to its adherents. An author must also be allowed to fully provoke criticism and question harmful political actions. For example, the discrimination policy driven by the Nazi Party led to the deaths of many innocent people as a result of the war. Authors are also allowed to freely rediscover history in their literary works.