by Yvonne Tan

We are no stranger to anxieties surrounding halal consumption practices and the danger of contamination making waves in the media with a variety of non-halal spaces available. Back in 2014, there was the Cadbury Dairy Milk chocolate scare where initial tests by Health Ministry (KKM) found traces of pork DNA before JAKIM did another round of tests to dispute this. Long story short, a boycott soon followed suit and the two products where traces of pork were found in was withdrawn. The Year of the Dog and the Pig on the Chinese Zodiac lunar calendar meant the animals were going to be depicted in decorations, advertising and so on for the New Year Celebrations.

If you thought that the problem with “babi” was confined to Malaysia alone, well think again. Who could forget when Dua Lipa’s Instagram caption caused a fiasco among Malaysians for wishing her father happy birthday, calling him “babi” as it meant dad in Albanian. After being mocked for using the word by Malaysians, she edited the caption as to “Happy Birthday Dad”. In a similar instance, a K-pop dancer coincidentally named Babi had received the same treatment. She responded differently releasing an angry statement on Instagram as well to Malaysians stating “I am not interested in your language, so it doesn’t matter what my name means in your language. And I didn’t know your country, but I don’t want to know it anymore.”

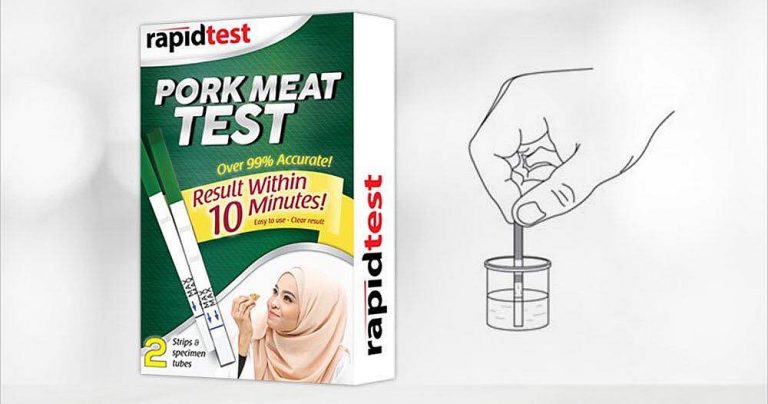

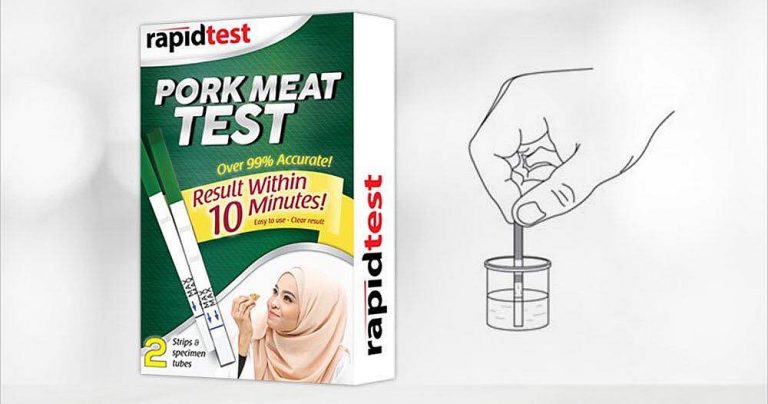

Iftitah Solutions (M) Sdn Bhd, owner of the brand Rapidtest released a product in 2019 called Pork Meat Test that claims to be able to detect pig DNA content in food, delivering results with 99% accuracy within 10 minutes. It was eventually written off by JAKIM, stating that this might lead to confusion and that authorities should be left to handle enforcement of halal products.

Iftitah Solutions (M) Sdn Bhd, owner of the brand Rapidtest released a product in 2019 called Pork Meat Test that claims to be able to detect pig DNA content in food, delivering results with 99% accuracy within 10 minutes. It was eventually written off by JAKIM, stating that this might lead to confusion and that authorities should be left to handle enforcement of halal products.

This time around it involves OLDTOWN White Coffee, where a TikTok user @sazz999ritz accused the restaurant of using pork meat in their Mee Kari. Quickly many defended OLDTOWN stating they were halal-certified by JAKIM to acknowledging that there is a common fear that Chinese people are out to contaminate food consumed by Malay Muslims. Another debate that arose was the expensive price of pork itself as a reason that Chinese people do not have an incentive to switch out a chicken product for pork. Some poked fun upholding this reasoning using the Chinese stereotype that they are “kiam siap”.

Meanwhile headlines from throughout the media ranged into two camps from “Restoran Halal terkenal jual mi kari babi”, “Oldtown White Coffee nafi produk mengandungi daging babi” to “Responsible Netizens Call Out Fake News After OLDTOWN White Coffee Accused Of Serving Pork Instead Of Chicken”. Ministry of Domestic Trade and Consumer Affairs (KPDNHEP) took the complaint seriously and did an inspection under Perintah 3(1)(a) Perihal Dagangan (Takrif Halal) 2011. They checked their halal certification to the ingredients itself while JAKIM confirmed that their Mee Kari were halal.

While some rushed to support OLDTOWN’s food, this continued to raise some eyebrows across Twitterjaya. Comments included that it was always better to eat at a Malay Muslim establishment without a JAKIM halal certification rather than one own and operated by a Chinese with certification, further signalling a distrust in the audit process in securing halal consumption. As the OLDTOWN controversy died down, another came around.

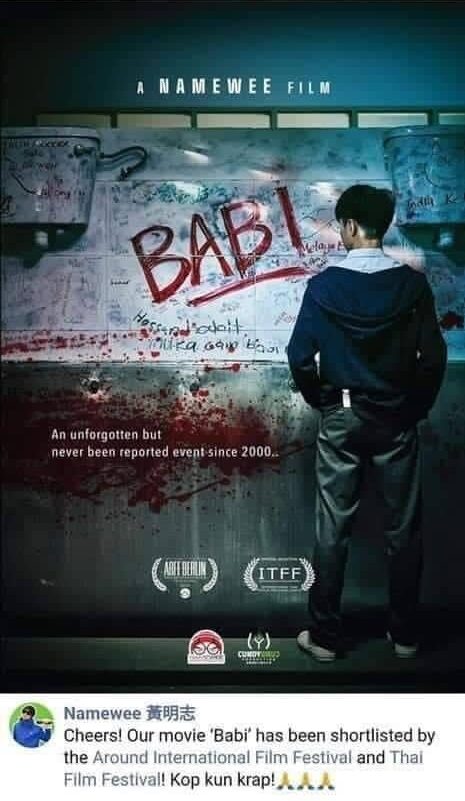

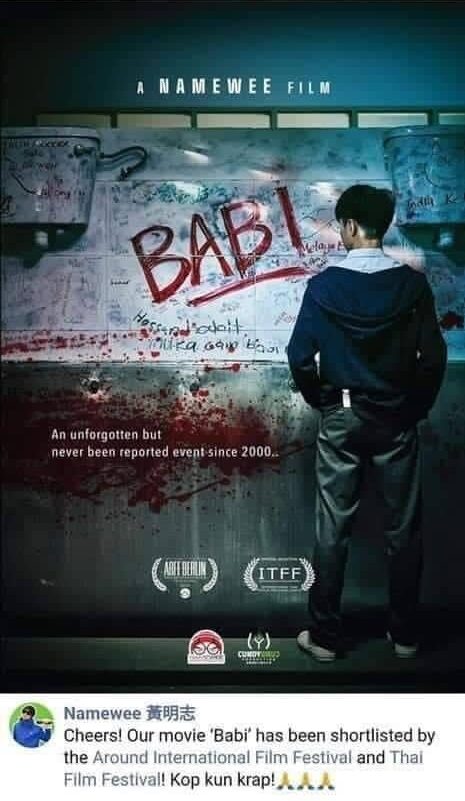

Namewee, who is no stranger to controversies since his parody of Negarakuku, is once again at the center of public attention for his film conspicuously named Babi. After Namewee celebrated his international nominations at the Open World Toronto Film Festival, Around International Film Festival and Thai Film Festival the Perikatan Nasional Youth lodged a report specifically against the film’s poster. It featured a vandalized wall of a toilet with words like “Cina babi” other racial slurs such as “Melayu B-“ and “Indian K-“, not revealing the full derogatory slur of the other races. Namewee claimed the film was banned in Malaysia and is based on an alleged race-war that started innocently in a Malaysian high school in 2000 and covered up.

Namewee, who is no stranger to controversies since his parody of Negarakuku, is once again at the center of public attention for his film conspicuously named Babi. After Namewee celebrated his international nominations at the Open World Toronto Film Festival, Around International Film Festival and Thai Film Festival the Perikatan Nasional Youth lodged a report specifically against the film’s poster. It featured a vandalized wall of a toilet with words like “Cina babi” other racial slurs such as “Melayu B-“ and “Indian K-“, not revealing the full derogatory slur of the other races. Namewee claimed the film was banned in Malaysia and is based on an alleged race-war that started innocently in a Malaysian high school in 2000 and covered up.

By now, it is clearer that these outrages are from the cultural politics of food risk as informed by race and religion. Babi is the abject other not only because it is considered to be haram and against the Malay Muslim identity but that “it lies there, quite close, but it cannot be assimilated” given how esteemed pork is to the Malaysian Chinese identity. It has become the defining factor of what demarcates and distinguishes oneself from the opposite of oneself. This cultural narrative that babi is a threat that one will continuously be confronted by given the presence of an identity that celebrates pork, has thus been passed down.

The disgust and uneasiness associated with babi “is thus not the lack of cleanliness or health that causes abjection but what disturbs identity, system, and order. What does not respect borders, positions, rules. The in-between, the ambiguous, the composite”. [1] When the clear distinction is no longer there, there is outrage as it threatens what is thought to be the core of one’s identity–in this case is Islam–which the nation-state is supposed to be structured on.

In the case of OLDTOWN, it highlights increasingly there is a wider rupture in food trust with Malaysia Halal Certification under the purview of JAKIM. Thus, this ambiguity calls for people to take things into their own hands such as with Rapidtest, choosing to support specifically Malay Muslim establishments or eating at a restaurant situated far from a Chinese restaurant in fear of pork particles travelling through the air.

People have become cynical to the halal certification process where “officials would request cash payments above the statutory fees in order to guarantee registration. Municipal councils and the fire department, too, would request such payments to issue the necessary documents required by JAKIM for halal product and premises applications.” [2] It has become but the norm with the high rates of rejected applications, lack of quality control officers, the proliferation of fake halal certificates with JAKIM having total purview on the matter.

Calling out corruption practices only leads to backlash such as the now-deleted allegations against JAKIM for purposely delaying the restaurant’s halal certification to for a bribe. Hence, such seemingly “drastic” measures to ensure one’s food is halal may stem from recognising JAKIM’s ineffectiveness and in the process avoiding establishments that have no personal incentive to be halal. The quick response by the government in order to ensure the dish was indeed halal after the video went viral is also a display of the effectiveness of their agencies in ensuring there is no food risk.

During the OLDTOWN controversy, there was some discussion on what is considered “haram” is always more or less exclusive to only to pork and the specific usage of “babi”. Bringing up that there is no equal outrage with corruption which is equally if not more haram. A particular video with an unknown source was circulated during this time where a man speaks about how the idea that dogs and pigs are haram are instilled since birth and wished people saw corruption as something more haram as it affects more than one person.

Not to mention, as noted earlier, recurring controversies surrounding babi are not confined only to whether a food is halal or haram but a need to make this term exclusively forbidden, calling out international figures who have no knowledge of the term in Malaysia. Eventhough “pig” is a derogatory term elsewhere, there is an added quality babi holds that no exceptions can be made for the word to mean something else only reveals how much weight the term holds and also how much of a national preoccupation it is.

In this regard, the word provokes shock and disgust to the point one is unable to look beyond its set-in-stone meaning and understanding of other cultures. Babi is the antithesis of what rojak / kebudayaan rojak is. While babi is a point of contention, representing lack of compatibility between cultures and uneasiness about not observing Islamic law with the cultural disparity, rojak on the other hand “constitutes a useful set of images for reflecting on the politics of commensality, intercultural exchanges, and identity hybridity and belonging”. [3]

[1] Kristeva, Julia. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. Translated by Leon S. Roudiez. Columbia University Press, 1982. p. 1, 4.

[2] Duruz, Jean, and Gaik Cheng Khoo. Eating together: Food, space, and identity in Malaysia and Singapore. Rowman & Littlefield, 2014p. 2.

[3] https://www.themalaysianinsight.com/s/189692

We’re proud to announce that one of our PFK films, The House Without a Ground (Rumah Nda Bertanah) by Putri Purnama Sugua, which won the title of best director and storyline at our event, is nominated for the Short Fiction Category under the Calcutta International Short Film Festival 2020!

We’re proud to announce that one of our PFK films, The House Without a Ground (Rumah Nda Bertanah) by Putri Purnama Sugua, which won the title of best director and storyline at our event, is nominated for the Short Fiction Category under the Calcutta International Short Film Festival 2020! Kami dengan bangga mengumumkan bahawa salah satu filem PFK kami, Rumah Ndak Bertanah karya Putri Purnama Sugua, yang telah memenangi pengarah dan storyline terbaik di PFK kami, telah dinominasikan untuk ‘Fiksyen Pendek Terbaik’ di Festival Filem Pendek Antarabangsa di Calcutta!

Kami dengan bangga mengumumkan bahawa salah satu filem PFK kami, Rumah Ndak Bertanah karya Putri Purnama Sugua, yang telah memenangi pengarah dan storyline terbaik di PFK kami, telah dinominasikan untuk ‘Fiksyen Pendek Terbaik’ di Festival Filem Pendek Antarabangsa di Calcutta!

PEN, untuk makluman anda adalah sebuah kelab sejagat yang menghimpunkan pengarang, editor, pemilik kedai buku, penerjemah dan pengamal teater-filem (khusus dramaturgis) yang berpangkalan di London. Sejak kelahirannya, PEN memberikan tumpuan kepada kerja-kerja membela dan melindungi pengarang dari tekanan dan kezaliman pihak berkuasa. PEN juga meraikan apa sahaja bahasa yang dipilih oleh pengarang dalam karyanya – tanpa prejudis – asalkan karya itu tujuannya demi kemanusiaan.

PEN, untuk makluman anda adalah sebuah kelab sejagat yang menghimpunkan pengarang, editor, pemilik kedai buku, penerjemah dan pengamal teater-filem (khusus dramaturgis) yang berpangkalan di London. Sejak kelahirannya, PEN memberikan tumpuan kepada kerja-kerja membela dan melindungi pengarang dari tekanan dan kezaliman pihak berkuasa. PEN juga meraikan apa sahaja bahasa yang dipilih oleh pengarang dalam karyanya – tanpa prejudis – asalkan karya itu tujuannya demi kemanusiaan. Seorang Nazi, yang hadir dalam delegasi dari Jerman telah menghalang Ernst Toller, seorang penulis teater Yahudi-Jerman yang hidup dalam buangan daripada berucap mengutuk Nazisme (dan tindakan membakar buku). Satu suara yang solid, kuat, formidable dan meyakinkan telah terbit dari persidangan itu. Para pengarang bersetuju untuk menolak usul Jerman mendokong kebebasan bersuara penuh (justeru menerima Nazisme) lantas kembali memihak kepada prinsip-prinsip yang telah mereka mandatkan. Pasukan dari Jerman marah lantas membantah, langsung bertindak untuk keluar dari Persidangan. Mereka malah memilih untuk keluar daripada PEN, sehinggalah selepas Perang Dunia Kedua.

Seorang Nazi, yang hadir dalam delegasi dari Jerman telah menghalang Ernst Toller, seorang penulis teater Yahudi-Jerman yang hidup dalam buangan daripada berucap mengutuk Nazisme (dan tindakan membakar buku). Satu suara yang solid, kuat, formidable dan meyakinkan telah terbit dari persidangan itu. Para pengarang bersetuju untuk menolak usul Jerman mendokong kebebasan bersuara penuh (justeru menerima Nazisme) lantas kembali memihak kepada prinsip-prinsip yang telah mereka mandatkan. Pasukan dari Jerman marah lantas membantah, langsung bertindak untuk keluar dari Persidangan. Mereka malah memilih untuk keluar daripada PEN, sehinggalah selepas Perang Dunia Kedua. Apakah bentuk kebencian yang ditolak dalam karya sastera?

Apakah bentuk kebencian yang ditolak dalam karya sastera?

Iftitah Solutions (M) Sdn Bhd, owner of the brand Rapidtest released a product in 2019 called

Iftitah Solutions (M) Sdn Bhd, owner of the brand Rapidtest released a product in 2019 called  Namewee, who is no stranger to controversies since his parody of Negarakuku, is once again at the center of public attention for his film conspicuously named Babi. After Namewee celebrated his international nominations at the Open World Toronto Film Festival, Around International Film Festival and Thai Film Festival the Perikatan Nasional Youth lodged a report specifically against the film’s poster. It featured a vandalized wall of a toilet with words like “Cina babi” other racial slurs such as “Melayu B-“ and “Indian K-“, not revealing the full derogatory slur of the other races. Namewee claimed the film was banned in Malaysia and is based on an alleged race-war that started innocently in a Malaysian high school in 2000 and covered up.

Namewee, who is no stranger to controversies since his parody of Negarakuku, is once again at the center of public attention for his film conspicuously named Babi. After Namewee celebrated his international nominations at the Open World Toronto Film Festival, Around International Film Festival and Thai Film Festival the Perikatan Nasional Youth lodged a report specifically against the film’s poster. It featured a vandalized wall of a toilet with words like “Cina babi” other racial slurs such as “Melayu B-“ and “Indian K-“, not revealing the full derogatory slur of the other races. Namewee claimed the film was banned in Malaysia and is based on an alleged race-war that started innocently in a Malaysian high school in 2000 and covered up.

Unions in Malaysia are categorised according to the private sector, public sector, employers’ unions and unions in statutory bodies and local authorities. Within the private sector, there can be national unions, that tries to cover workers of the same occupation, and in-house/enterprise unions for workers with the same employer [1]. Malaysian Trades Union Congress (MTUC) was established in 1949 to encompass unions from both public and private sector, of various occupations and trades, however, it does not qualify as a union, rather it is registered as a society.

Unions in Malaysia are categorised according to the private sector, public sector, employers’ unions and unions in statutory bodies and local authorities. Within the private sector, there can be national unions, that tries to cover workers of the same occupation, and in-house/enterprise unions for workers with the same employer [1]. Malaysian Trades Union Congress (MTUC) was established in 1949 to encompass unions from both public and private sector, of various occupations and trades, however, it does not qualify as a union, rather it is registered as a society. Despite anti-union tactics employed by companies, there are many instances till today that unionising works even in an environment that is highly unfavourable to organising. Collective bargaining is usually favoured, and if negotiations continue to remain in a deadlock the issue is taken to the Industrial Court. The

Despite anti-union tactics employed by companies, there are many instances till today that unionising works even in an environment that is highly unfavourable to organising. Collective bargaining is usually favoured, and if negotiations continue to remain in a deadlock the issue is taken to the Industrial Court. The

Abortion services are available in the private sector that is, of course, clandestine about but comes with high costs. Due to socio-economic reasons,

Abortion services are available in the private sector that is, of course, clandestine about but comes with high costs. Due to socio-economic reasons,  At a time when strenuous calls for national unity are made by the Prime Minister and Malaysia Prihatin (Malaysia Cares) is the guiding principle for the nation’s celebration of the 63rd anniversary of Merdeka Day and the 57th anniversary of Malaysia Day, it is an outrage that a Member of Parliament who sits on the Government’s benches shows little concern for the need to rebuild the nation but instead intentionally promotes feelings of ill will and hostility on the ground of religion in a significant segment of the population. Having assailed their Holy Book, the Member of Parliament then categorically stated that Christians have no right to be offended. Recalcitrant and reportedly, unwilling to withdraw or apologise for his demeaning words, this lawmaker must be unreservedly censured and rebuked by all right-minded people. Not having taken to date, any apparent action to rein in and admonish its member for his divisive and incendiary remarks, the party to which he belongs, being a component member of the ruling coalition, should denounce such egregious behaviour. No person being above the law, relevant authorities also need to undertake appropriate investigations into the offensive conduct of this lawmaker.

At a time when strenuous calls for national unity are made by the Prime Minister and Malaysia Prihatin (Malaysia Cares) is the guiding principle for the nation’s celebration of the 63rd anniversary of Merdeka Day and the 57th anniversary of Malaysia Day, it is an outrage that a Member of Parliament who sits on the Government’s benches shows little concern for the need to rebuild the nation but instead intentionally promotes feelings of ill will and hostility on the ground of religion in a significant segment of the population. Having assailed their Holy Book, the Member of Parliament then categorically stated that Christians have no right to be offended. Recalcitrant and reportedly, unwilling to withdraw or apologise for his demeaning words, this lawmaker must be unreservedly censured and rebuked by all right-minded people. Not having taken to date, any apparent action to rein in and admonish its member for his divisive and incendiary remarks, the party to which he belongs, being a component member of the ruling coalition, should denounce such egregious behaviour. No person being above the law, relevant authorities also need to undertake appropriate investigations into the offensive conduct of this lawmaker.

1) Spirits of Resistance and Capitalist Discipline: Factory women in Malaysia by Aihwa Ong

1) Spirits of Resistance and Capitalist Discipline: Factory women in Malaysia by Aihwa Ong 2) Migration and Diaspora in Modern Asia by Sunil Amrith

2) Migration and Diaspora in Modern Asia by Sunil Amrith 3) Wage Labour in Southeast Asia since 1840: Globalisation, the International Division of Labour and Labour Transformations by Amarjit Kaur

3) Wage Labour in Southeast Asia since 1840: Globalisation, the International Division of Labour and Labour Transformations by Amarjit Kaur 4) Cage of Freedom: Tamil identity and the ethnic fetish in Malaysia by Andrew Willford

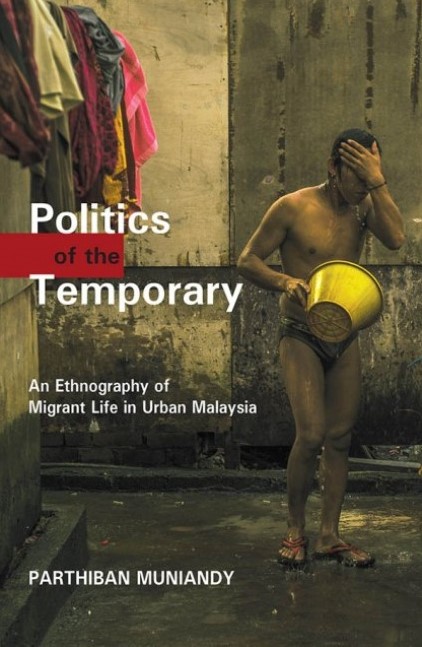

4) Cage of Freedom: Tamil identity and the ethnic fetish in Malaysia by Andrew Willford 5) Politics of the Temporary: An Ethnography of Migrant Life in Urban Malaysia by Parthiban Muniandy

5) Politics of the Temporary: An Ethnography of Migrant Life in Urban Malaysia by Parthiban Muniandy