by Yvonne Tan

In April 2021 a viral Google satellite image of a heavily deforested land located next to the Kuantan District Forest Department prompted the Pahang Forestry Department to hold a press conference to clarify the ownership of the land pictured. The Pahang Forestry Department Director Datuk Mohd. Hizamri Mohd. Yassin stated that the land was privately owned outside the Bukit Galing Forest Reserve and explained that mining activities have been put to a stop twice in 2016 and 2017.

Later in June, Malaysiakini reports on a company with links to the Pahang royal family plans to mine iron from the degazetted Som Forest reserve at Kuala Tembeling on top of a previous royalty-linked mining project near Tasik Chini in Pekan. Days later, several questioned this move on Tengku Hassanal Ibrahim Alam Shah’s Instagram video post of himself doing push-ups with the hashtag #pushUp4environment. Soon after this, he proposes mining activities to be stopped, ordered the former mining areas be reforested and for the expansion of the Tasik Chini forest reserve. This was also in conjunction with a Facebook post going viral which claimed a new mining site was allowed to open near Tasik Chini after March 2019. The State Land and Mines director’s office had to release a statement that no new mining leases nor exploration licenses have been issued since then.

Aside from Pahang, on 12 August the Selangor government had completed the legal process for the degazettement of Kuala Langat North Forest Reserve for mixed commercial development despite many online petitions and signatures objecting to the proposal since January. A week later, the Selangor state government decided to postpone the degazettement despite 54% of the 931.17 h.a. had already been degazetted and following more criticism decided to re-gazette Kuala Langat forest reserve.

The coalition “Pertahankan Hutan Simpan Kuala Langat Utara (PHSKLU)” [https://selamatkanhsklu.carrd.co/] encouraged sending pressure emails to the Selangor MB and protest on social media using the hashtags #HutanPergiMana #SelamatkanHSKLU #SaveKLNFR #RevokeTheDegazettement. Take for example, @iqtodabal’s Instagram reels where he spoke about the Kuala Langat Forest Reserve and those who would profit from their degazettement garnered over 59,000 views while a similar video on Tasik Chini got over 244,000 views at the time of writing. It is hard to pinpoint to a particular reason why both state governments have suddenly decided to listen to public outcry and the reality could be a mix of pressure from Orang Asli, NGOs and CSOs, media attention and social media outrage. PHSKLU in their latest press statement attributed media as one of the major contributing factors on the reversal of degazettement: “We also recognise the important role played by the local media in their extensive coverage of the issue over the past 18 months, including more than 200 articles and interviews in various languages”.

The RM 46 billion Penang South Reclamation (PSR) megaproject also got cancelled in early September due to public pressure. The proposed megaproject would include 3 islands the size of 4500 acres that would cause disruption to fishermen’s livelihoods, marine ecosystems and coastal habitats to not only Penang but also Perak where sand mining would take place. Although the Penang government may apply for judicial review against the Appeal Board under the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), this move came hard-fought by Penang Fishermen’s Association (PenMutiara) who challenged the EIA assessment, environmental organisations, and social media campaigns with #PenangTolakTambak trending on Twitter in June. The volunteers of Penang Tolak Tambak, a coalition between PenMutiara and Penang Forum initiated the online campaign and Khoo Salma Naution, a member of Penang Forum stated “With the MCO, we can’t physically protest, so we’re trying to do things through social media. It’s really good to see a local environmental issue trending on Twitter, I don’t remember the last time that happened, especially since a lot of people will look at this as a Penang problem.”

There is clearly a pattern here. Although the cancellations of these projects that come after public pressure might seem like the government does listen, month after month might seem like the government does listen to demands of affected communities, the public, and environmental groups, it is not the case. Take for example, Shakila Zen who has been vocal against degazetting the Kuala Langat Reserve received an anonymous letter threatening an acid attack against her with a replica of a severed hand. Meanwhile, the fishermen associations have appealed against the Department of Environment’s approval of the PSR project since 2019 while many voiced their concerns since the approval of the project in 2015. Not to mention, Penang Tolak Tambak were also closely associated with Save Portuguese Community Action Committee (SPAC) in Malacca, Koalisi Selamatkan Teluk Jakarta, Kumpulan Indah Tanjung Aru (KTIA) in Sabah and Persatuan Aktivist Sahabat Alam (KUASA) in Perak in collectively resisting against land reclamation culminating in a joint statement “Stop Stealing our Seas, joint statement by Malaysia-Indonesia groups against reclamation” which has garnered almost 129,000 signatures.

If anything, the continual outrage and viralising of problematic development projects that would adversely affect communities and climate change reveal there is a clear awareness that powers that be stood to benefit most from the destruction of our environment. As a developing country that saw the rapid restructuring of our economy for the proliferation of white elephant projects under the guise of national development that came with Wawasan 2020 that is now behind us, maybe there is a shift in a Malaysia that we would like. Criticising callous development at the expense of the environment has now become the norm.

State governments have become private sector monopolies, where ownership and control have been legitimized via “decentralised” power made up of political elites. In the case of Pahang and Selangor, after public outcry, the state governments would quickly shift blame to the private companies to whom they have sold licenses to. However, there is persistent attention, both online and offline, on respective state management of the environment calling for more transparency and accountability. This does not discount the hard work of on-the-ground organisations and advocacy groups, but rather harking to the beginnings of maybe a wider climate movement in Malaysia, one which gives power to the communities most affected by climate change.

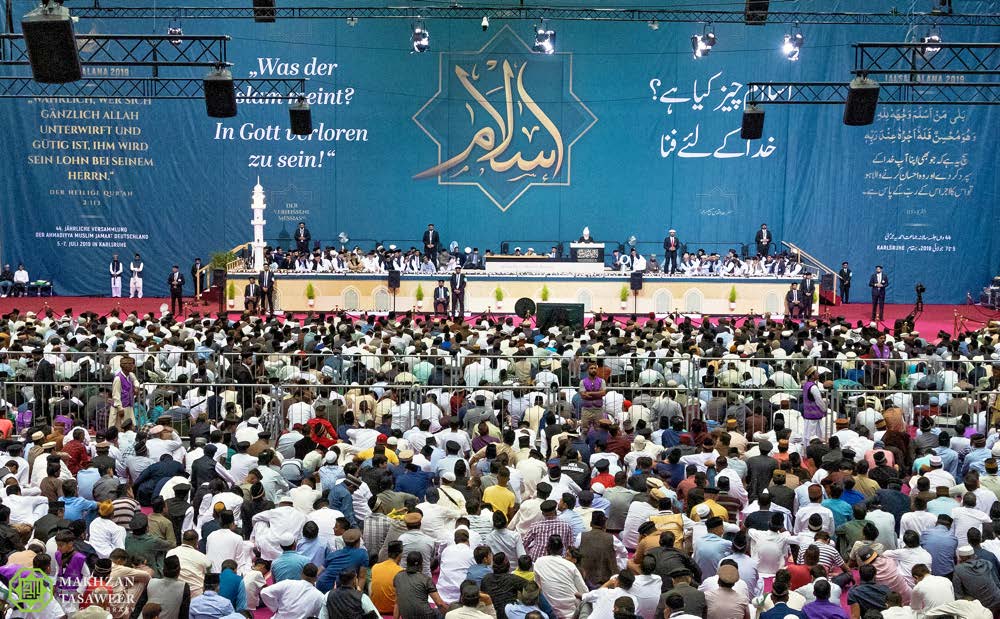

This year marks the return of Jalsa Salana UK after its 2-year gap due to the Covid-19 pandemic., though accompanied by various health and safety measures. It was held on the 5th to 8th of August at the Hadeeqatul Mahdi, hosting a total of 8,887 invitees – 6,709 and 2,168 men and women respectively; though this pales in comparison to the usual 35,000 Ahmadis it usually draws from around the world.

This year marks the return of Jalsa Salana UK after its 2-year gap due to the Covid-19 pandemic., though accompanied by various health and safety measures. It was held on the 5th to 8th of August at the Hadeeqatul Mahdi, hosting a total of 8,887 invitees – 6,709 and 2,168 men and women respectively; though this pales in comparison to the usual 35,000 Ahmadis it usually draws from around the world. The invitees were chosen by ballot while 4,000 Muslims who were unable to attend gathered virtually at 40 mosques and centers across the UK to watch the Jalsa. This stands testament to how Jalsa Salana is the largest annual Islamic convention in the UK, having run for over 50 years and organized every year by the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community (AMC)

The invitees were chosen by ballot while 4,000 Muslims who were unable to attend gathered virtually at 40 mosques and centers across the UK to watch the Jalsa. This stands testament to how Jalsa Salana is the largest annual Islamic convention in the UK, having run for over 50 years and organized every year by the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community (AMC) Through these addresses, Huzur commends the Jama’at’s great work – speaking of missionaries worldwide and testimonies from new believers. He speaks of the fruits of their labor, in the 211 mosques built, in the many new converts, in the numerous people reached through their publications and translations, and how connections between past and lost converts have been strengthened and rebuilt. He also details the good work done beyond the religious realm – speaking of their humanitarian and medical efforts in emergency situations worldwide.

Through these addresses, Huzur commends the Jama’at’s great work – speaking of missionaries worldwide and testimonies from new believers. He speaks of the fruits of their labor, in the 211 mosques built, in the many new converts, in the numerous people reached through their publications and translations, and how connections between past and lost converts have been strengthened and rebuilt. He also details the good work done beyond the religious realm – speaking of their humanitarian and medical efforts in emergency situations worldwide. The Huzur commands a powerful presence, one which invokes in Ahmaddi Muslims a spiritual and emotional experience. Beyond the teachings and sermons the Jalsa will impart them, the Jalsa presents Ahmaddi Muslims the privilege of being in his presence and the chance to serve and hopefully meet him.

The Huzur commands a powerful presence, one which invokes in Ahmaddi Muslims a spiritual and emotional experience. Beyond the teachings and sermons the Jalsa will impart them, the Jalsa presents Ahmaddi Muslims the privilege of being in his presence and the chance to serve and hopefully meet him.

There have been concerted

There have been concerted  Hence, there is a need to reframe languages thought of as “dialects” within Malaysia that reflect the many varieties of Malaysian Chinese identities. “Dialects” typically have a reputation as a language that people default to in order to fully express their anger. The mixing of languages in Malaysia is typically celebrated for multiculturalism and achievement of the 1Malaysia agenda but the discourse on individual Malaysian Chinese and Indian identities really only begins and ends with if you are banana or coconut. Rarely do we assess the internal dynamics and identities of being Malaysian Chinese beyond defending its right to exist. It is as Li Zishu 黎紫书 asks: “In our generation, we have no homeland nor cultural origin [in China]. We grow up here [Malaysia]. How do we face this place? How do we learn about ourselves?” [3]

Hence, there is a need to reframe languages thought of as “dialects” within Malaysia that reflect the many varieties of Malaysian Chinese identities. “Dialects” typically have a reputation as a language that people default to in order to fully express their anger. The mixing of languages in Malaysia is typically celebrated for multiculturalism and achievement of the 1Malaysia agenda but the discourse on individual Malaysian Chinese and Indian identities really only begins and ends with if you are banana or coconut. Rarely do we assess the internal dynamics and identities of being Malaysian Chinese beyond defending its right to exist. It is as Li Zishu 黎紫书 asks: “In our generation, we have no homeland nor cultural origin [in China]. We grow up here [Malaysia]. How do we face this place? How do we learn about ourselves?” [3]

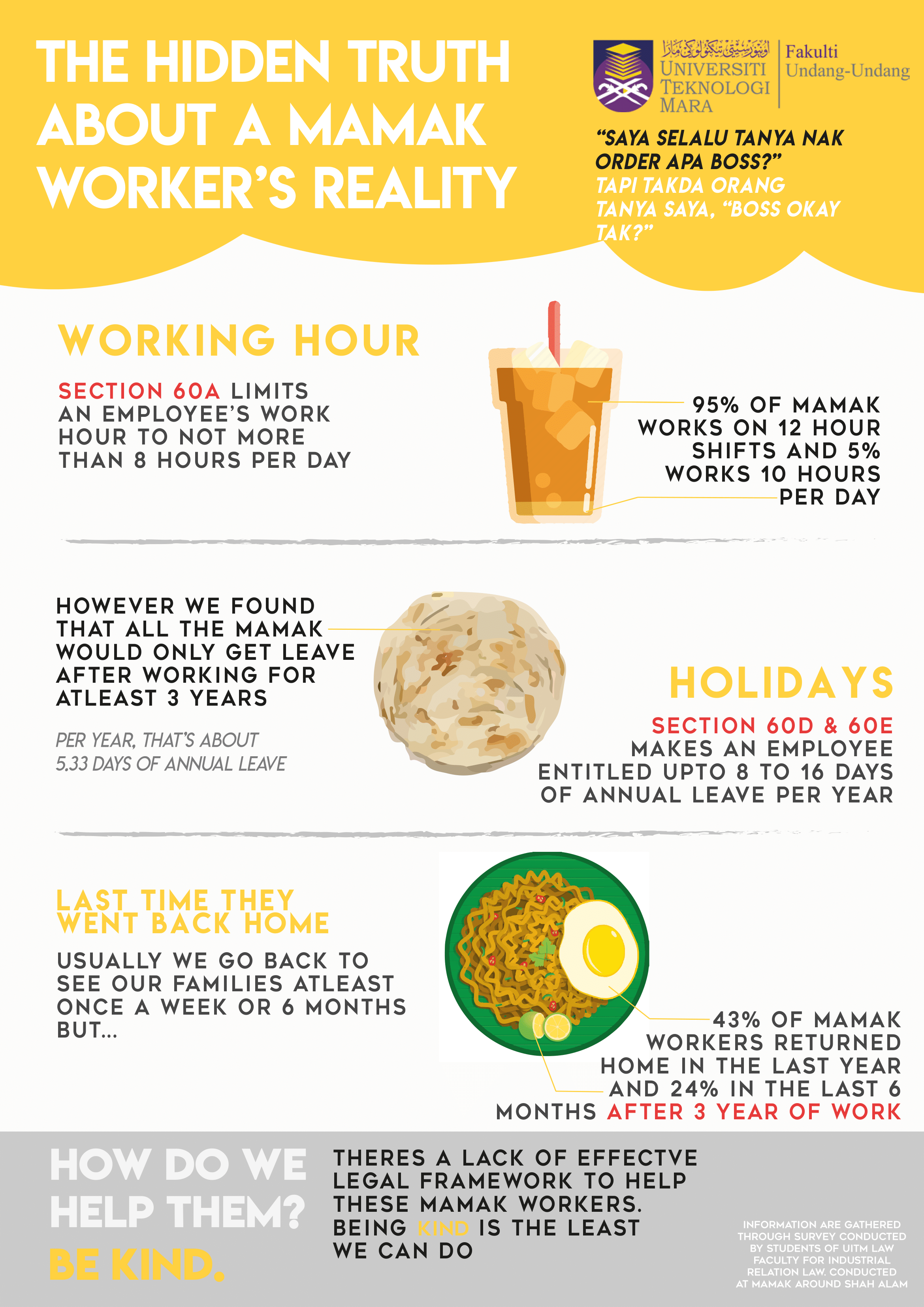

A UiTM study for a course assignment in January 2021 had conducted

A UiTM study for a course assignment in January 2021 had conducted  And it has only gotten worse with the new wave of raids on migrants following MCO 3.0 where videos of

And it has only gotten worse with the new wave of raids on migrants following MCO 3.0 where videos of  Hence, let us reassess the identity of the mamak which has become the exemplar of food as both a point of national unity and division. Lauded as democratic and popular spaces for multiculturalism when turning a blind eye to the plight of the migrant workers operating such stalls, the pandemic has amplified this divide. As memes of missing mamak food proliferate while another mass immigration crackdown is carried out, it is a dichotomy that we should reconcile with. Malaysian food continues to be a point of national pride for most of us and as empathy can be a starting point, there is a need to demand for change to the precarious systems that will eventually result in the end of such establishments with

Hence, let us reassess the identity of the mamak which has become the exemplar of food as both a point of national unity and division. Lauded as democratic and popular spaces for multiculturalism when turning a blind eye to the plight of the migrant workers operating such stalls, the pandemic has amplified this divide. As memes of missing mamak food proliferate while another mass immigration crackdown is carried out, it is a dichotomy that we should reconcile with. Malaysian food continues to be a point of national pride for most of us and as empathy can be a starting point, there is a need to demand for change to the precarious systems that will eventually result in the end of such establishments with

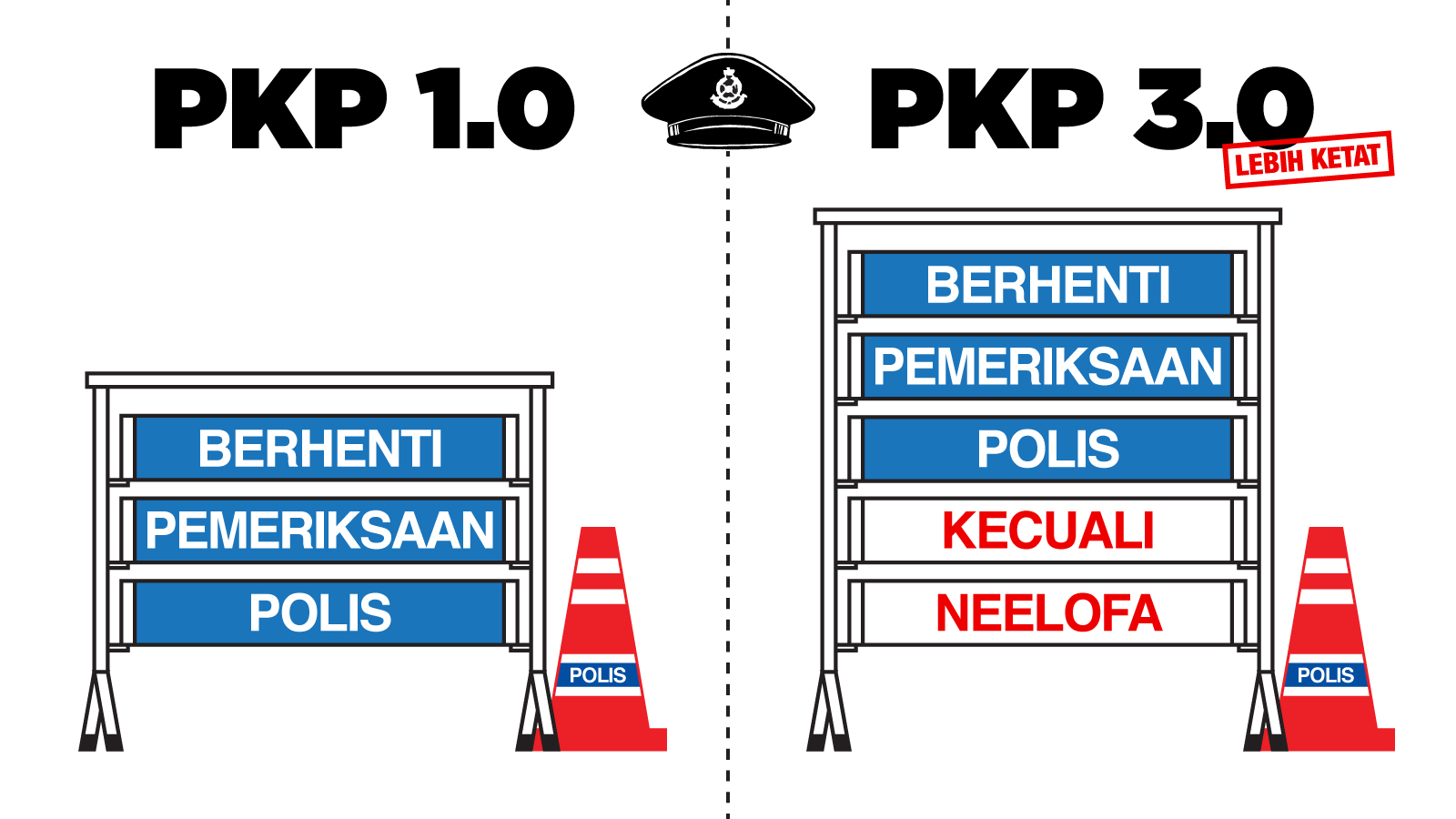

During the ongoing outrage directed against Neelofa, a small tide turned a little into questioning the police on a separate matter. In stark contrast within the span of almost a month, there have been two deaths in police custody at Gombak district police headquarters (IPD). Security guard Sivabalan Subramaniam died within an hour in police custody while cow milk trader A. Ganapathy succumbed to his injuries caused by police brutality after spending over a month at the Selayang Hospital’s intensive care unit. The

During the ongoing outrage directed against Neelofa, a small tide turned a little into questioning the police on a separate matter. In stark contrast within the span of almost a month, there have been two deaths in police custody at Gombak district police headquarters (IPD). Security guard Sivabalan Subramaniam died within an hour in police custody while cow milk trader A. Ganapathy succumbed to his injuries caused by police brutality after spending over a month at the Selayang Hospital’s intensive care unit. The

24 April 2021, Fahmi Reza lifted up the

24 April 2021, Fahmi Reza lifted up the

This brings us to Malaysia. Myanmar people continues to be viewed through the lens of not only as “migrant workers” but Pendatang Asing Tanpa Izin. The rhetoric of PATI spread like wildfire during COVID-19, implying there was immense trust in our systems to ensure no one was wrongly charged and belief that they were spreading the government’s resources thin. This is despite having little to no transparency and the immigration department’s long history of corruption and abuses, on top of its links to human trafficking. When the deportation of the 1,086 Myanmar nationals went through despite the Kuala Lumpur High Court order, while there were revived #MigranJugaManusia online protests, there was also a strong sentiment that they should simply be “sent back to where they came from”.

This brings us to Malaysia. Myanmar people continues to be viewed through the lens of not only as “migrant workers” but Pendatang Asing Tanpa Izin. The rhetoric of PATI spread like wildfire during COVID-19, implying there was immense trust in our systems to ensure no one was wrongly charged and belief that they were spreading the government’s resources thin. This is despite having little to no transparency and the immigration department’s long history of corruption and abuses, on top of its links to human trafficking. When the deportation of the 1,086 Myanmar nationals went through despite the Kuala Lumpur High Court order, while there were revived #MigranJugaManusia online protests, there was also a strong sentiment that they should simply be “sent back to where they came from”. Out of fear, Myanmar people have not publicly protested en masse in Malaysia unlike its diaspora in Thailand, Australia, Taiwan, Japan and so on. However, one high profile act of resistance was by Hein Htet Aung, from Selangor FC II. He celebrated his goal win with the three-finger salute. He was then suspended for a game, with netizens supporting the idea of “not bringing over one’s politics to another’s soil”. Echoing the same fear of importing instability, it is only fitting to say, “it must be a fragile system if it can be brought down by a few berries”.

Out of fear, Myanmar people have not publicly protested en masse in Malaysia unlike its diaspora in Thailand, Australia, Taiwan, Japan and so on. However, one high profile act of resistance was by Hein Htet Aung, from Selangor FC II. He celebrated his goal win with the three-finger salute. He was then suspended for a game, with netizens supporting the idea of “not bringing over one’s politics to another’s soil”. Echoing the same fear of importing instability, it is only fitting to say, “it must be a fragile system if it can be brought down by a few berries”. The

The  How is it done? The policy of the debate or the idea of Mubadalah begins by emphasizing the monotheism of Islam, the basis and core of the faith which is completely anti-patriarchal. The author argues that the Qur’an should not be misunderstood at all and that Prophet Muhammad came to humanize the ignorant Arabs, and to return the status of humanity to women. Before the arrival of the Prophet, unfortunately, women were not considered human. Women in the age of ignorance were oppressed at will. They are slaves to lust, women are given gifts, debt security, hostages, to be raped, married or divorced, to the point of being buried alive simply because of their gender.

How is it done? The policy of the debate or the idea of Mubadalah begins by emphasizing the monotheism of Islam, the basis and core of the faith which is completely anti-patriarchal. The author argues that the Qur’an should not be misunderstood at all and that Prophet Muhammad came to humanize the ignorant Arabs, and to return the status of humanity to women. Before the arrival of the Prophet, unfortunately, women were not considered human. Women in the age of ignorance were oppressed at will. They are slaves to lust, women are given gifts, debt security, hostages, to be raped, married or divorced, to the point of being buried alive simply because of their gender. Therefore, this book not only re-examines the gender text as a whole, but also ranks and establishes women as equal to men. This is done so that the claim that women are the source of slander is refuted and no longer accepted recklessly. The issues of nusyuz, polygamy, iddah and child-rearing are given a great context so that they are not isolated in just one space. It seeks to liberate women where the issue of women’s prominence as scholars are given attention. This includes resolutely challenging the position of women as the prayer imam. Then, the hadith ‘it will not be happy for the people to leave the affairs of their leadership to a woman’ as an example is seen not on the issue of gender but rather, is actually a prophecy of the Prophet Muhammad on the fall of the Persian empire at the hands of a woman. Reading this perspective provides us with logic for today’s world where women’s leadership is far more successful than men’s, as highlighted by Chancellor Merkel in Germany or the Prime Minister of New Zealand, Jacinda Adern.

Therefore, this book not only re-examines the gender text as a whole, but also ranks and establishes women as equal to men. This is done so that the claim that women are the source of slander is refuted and no longer accepted recklessly. The issues of nusyuz, polygamy, iddah and child-rearing are given a great context so that they are not isolated in just one space. It seeks to liberate women where the issue of women’s prominence as scholars are given attention. This includes resolutely challenging the position of women as the prayer imam. Then, the hadith ‘it will not be happy for the people to leave the affairs of their leadership to a woman’ as an example is seen not on the issue of gender but rather, is actually a prophecy of the Prophet Muhammad on the fall of the Persian empire at the hands of a woman. Reading this perspective provides us with logic for today’s world where women’s leadership is far more successful than men’s, as highlighted by Chancellor Merkel in Germany or the Prime Minister of New Zealand, Jacinda Adern.