by Jeannette Goon

What are Malaysian stories?

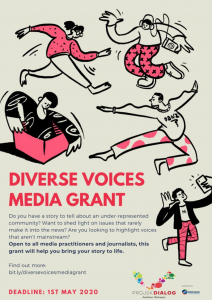

When we first put a call out for grant submissions, we were expecting diversity. But even so, we were surprised at how extensive the diversity in media could be.

When we first put a call out for grant submissions, we were expecting diversity. But even so, we were surprised at how extensive the diversity in media could be.

We received pitches for stories about the stateless community in Sabah, Chinese education in Malaysia, psychological trauma among children with medical conditions that affect body image.

There was also diversity in medium — from essays to VR documentaries to interactive digital articles.

Ultimately, out of the 47 submissions we received, we could only select 10. This was a very difficult task, considering many of the submissions were of high quality and highlighted stories that we were interested in.

Helping us with this difficult task was our selection committee, which consisted of:

Victoria Cheng, Project Manager, Projek Dialog

Jeannette Goon, Program Officer, Projek Dialog

Sharaad Kuttan, Senior Anchor, Astro Awani

Abu Hayat, Migrant Worker’s Rights Activist

Justin Wong, Founder, Write Handed

The selection process involved an individual evaluation, where each member of the selection committee received access to all the submissions and assessed them individually, as well as a group evaluation where all selection committee members met to discuss the final 10.

The selection process involved an individual evaluation, where each member of the selection committee received access to all the submissions and assessed them individually, as well as a group evaluation where all selection committee members met to discuss the final 10.

The 10 grant recipients are:

Aidila Razak (Malaysiakini)

For an interactive digital article, accompanied by video and podcast, on unaccompanied minor refugees.

Vinodh Pillai

For a series of written accounts of lived realities from those working in the different, vulnerable jobs in the local sex industry and how their livelihoods have been affected during the COVID-19 lockdown.

Rupa Subramaniam

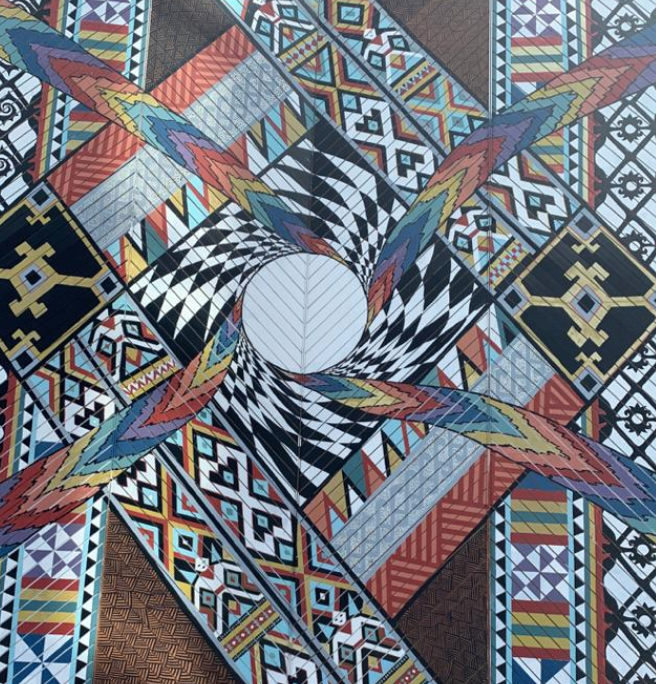

For a virtual mixed media art exhibition and a documentary featuring the stories of 30 Malaysian women translated into body art.

Loh Yi Jun

For Take a Bao, a podcast that tells the stories of the unrepresented food culture of Asia, starting off with stories in Malaysia/Southeast Asia.

Kristy Tan Wei Shia

For a podcast series inviting diverse sources to have a chat on topics related to motherhood. One of the topics it aims to explore is: How is motherhood valued and shaped by our different cultures and faiths?

Allie Hill (in collaboration with Amin Kamrani)

For an ebook featuring members of the refugee community, that will showcase how multi-talented they are and the skills that they have. The book will be visually led, accompanied by short text.

Tan Su Lin

For a Malay language story highlighting the effects of climate change on indigenous communities in Malaysia.

Ricardo Unto (Daily Express)

For a video report on ritual specialists from Tuaran and Penampang in Sabah. These “ritual specialists” are the guardians of the native Kadazan Dusun community’s culture.

Zarif Ismail

For a VR documentary about the Batek tribe in Taman Negara. The film explores their settlement, spiritual practices, food gathering and their relationship with the forest.

Roshinee Mookaiah

For a short story competition to be run on a Humans of New York-inspired social media platform that features Malaysian Indians. People will be asked to submit short photo essays or videos and the grant money will be used for prize money, judges’ fees, advertising expenses and production of a final video.

Congrats to all grant recipients, and thank you to all who submitted!

For more information on the selection process, please read our selection guidelines for this grant.

This media grant is part of the Diverse Voices program run by Projek Dialog with the support of Internews. The main goal of the program is to promote religious freedom and under-represented communities in the media.

___________________________________________

Apakah itu cerita-cerita Malaysia?

Apabila kebukaan permohanan grant kami diterbitkan di laman media sosial, terdapat pengharapan untuk kepelbagaian. Tetapi walaupun begitu, kami amat kagum melihat betapa luasnya kepelbagaian media.

Kami menerima idea-idea mengenai komuniti yang tidak bernegara di Sabah, pendidikan Cina di Malaysia, trauma psikologi di kalangan kanak-kanak dengan keadaan perubatan yang mempengaruhi imej badan.

Terdapat juga kepelbagaian dalam perantara iaitu daripada karangan kepada dokumentari alam maya kepada artikel digital yang interaktif.

Akhirnya, daripada 47 permohonan yang kami terima, kami hanya dapat memilih 10. Ini merupakan tugas yang amat sukar, sedangkan terdapat pelbagai permohanan, idea yang berbagai disertakan dengan cerita-cerita yang kami minat.

Menolong kami dengan tugas yang sukar ini adalah jawatankuasa pemilihan kami, yang terdiri daripada:

Victoria Cheng, Pengurus Program, Projek Dialog

Jeannette Goon, Pegawai Program, Projek Dialog

Sharaad Kuttan, Pemberita Kanan, Astro Awani

Abu Hayat, Aktivis Hak Pekerja Migran

Justin Wong, Pengasas, Write Handed

Proses pemilihan melibatkan penilaian individu, di mana setiap ahli jawatankuasa mempunyai akses kepada semua permohonan dan penilaian secara berasingan dijalankan. Selain itu, penilaian secara berkumpulan juga dilaksanakan di mana semua ahli jawatankuasa pemilihan bertemu untuk membincangkan 10 finalis.

Proses pemilihan melibatkan penilaian individu, di mana setiap ahli jawatankuasa mempunyai akses kepada semua permohonan dan penilaian secara berasingan dijalankan. Selain itu, penilaian secara berkumpulan juga dilaksanakan di mana semua ahli jawatankuasa pemilihan bertemu untuk membincangkan 10 finalis.

10 penerima grant tersebut adalah:

Aidila Razak (Malaysiakini)

Artikel digital yang interaktif, disertai dengan video dan podcast tentang masyarakat pelarian bawah umur.

Vinodh Pillai

Untuk siri laporan bertulis yang bersiasat mengenai pekerjaan yang berbeza dan terdedah dalam industri seks tempatan dan bagaimana sumber pendapatan mereka terjejas semasa penyekatan oleh COVID-19.

Rupa Subramaniam

Untuk pameran seni media campuran maya dan dokumentari yang memaparkan kisah 30 wanita Malaysia yang diterjemahkan ke dalam seni badan.

Loh Yi Jun

Untuk Take a Bao, podcast yang menceritakan kisah budaya makanan Asia yang tidak diwakili, bermula dengan cerita-cerita di Malaysia / Asia Tenggara.

Kristy Tan Wei Shia

Untuk siri podcast yang mengundang sumber yang berbagai-bagai/pelbagai untuk membincangkan topik yang berkaitan dengan hal-hal keibuan. Salah satu topik yang ingin diterokainya ialah: Bagaimana perihal keibuan dihargai dan dibentuk oleh budaya dan kepercayaan kita yang berbeza?

Allie Hill (bekerjasama dengan Amin Kamrani)

Untuk ebook yang menampilkan ahli komuniti pelarian, yang akan menunjukkan bakat dan kemahiran yang mereka ada. Buku ini akan dipimpin secara visual, disertakan dengan teks pendek.

Tan Su Lin

Untuk cerita berbahasa Melayu yang menekankan kesan perubahan iklim terhadap masyarakat peribumi di Malaysia.

Ricardo Unto (Daily Express)

Untuk laporan video mengenai pakar ritual dari Tuaran dan Penampang di Sabah. “Pakar ritual” ini adalah penjaga-penjaga kepada budaya masyarakat Kadazan Dusun.

Zarif Ismail

Untuk dokumentari alam maya mengenai suku Batek di Taman Negara. Filem ini meceritakan tentang penempatan, amalan kerohanian, pengumpulan makanan dan hubungan mereka dengan hutan di sana.

Roshinee Mookaiah

Diilhamkan oleh Humans of New York, sebuah pertandingan cerpen akan diadakan di laman media sosial yang menampilkan masyarakat India Malaysia. Mereka akan diminta untuk menghantar esei foto pendek atau video. Wang daripada grant ini akan digunakan untuk memberikan hadiah berbentuk wang, pembayaran untuk hakim dan iklan, dan juga untuk pengeluaran sebuah video.

Tahniah kepada semua penerima grant kami, dan terima kasih kepada semua yang membuat permohonan!

Untuk maklumat lebih lanjut mengenai proses pemilihan, sila baca panduan pemilihan kami untuk grant ini.

Media grant ini adalah sebahagian dari program Diverse Voices yang dikendalikan oleh Projek Dialog dengan sokongan Internews. Matlamat utama program ini adalah untuk menggalakkan kebebasan beragama dan masyarakat yang kurang diwakili di media.

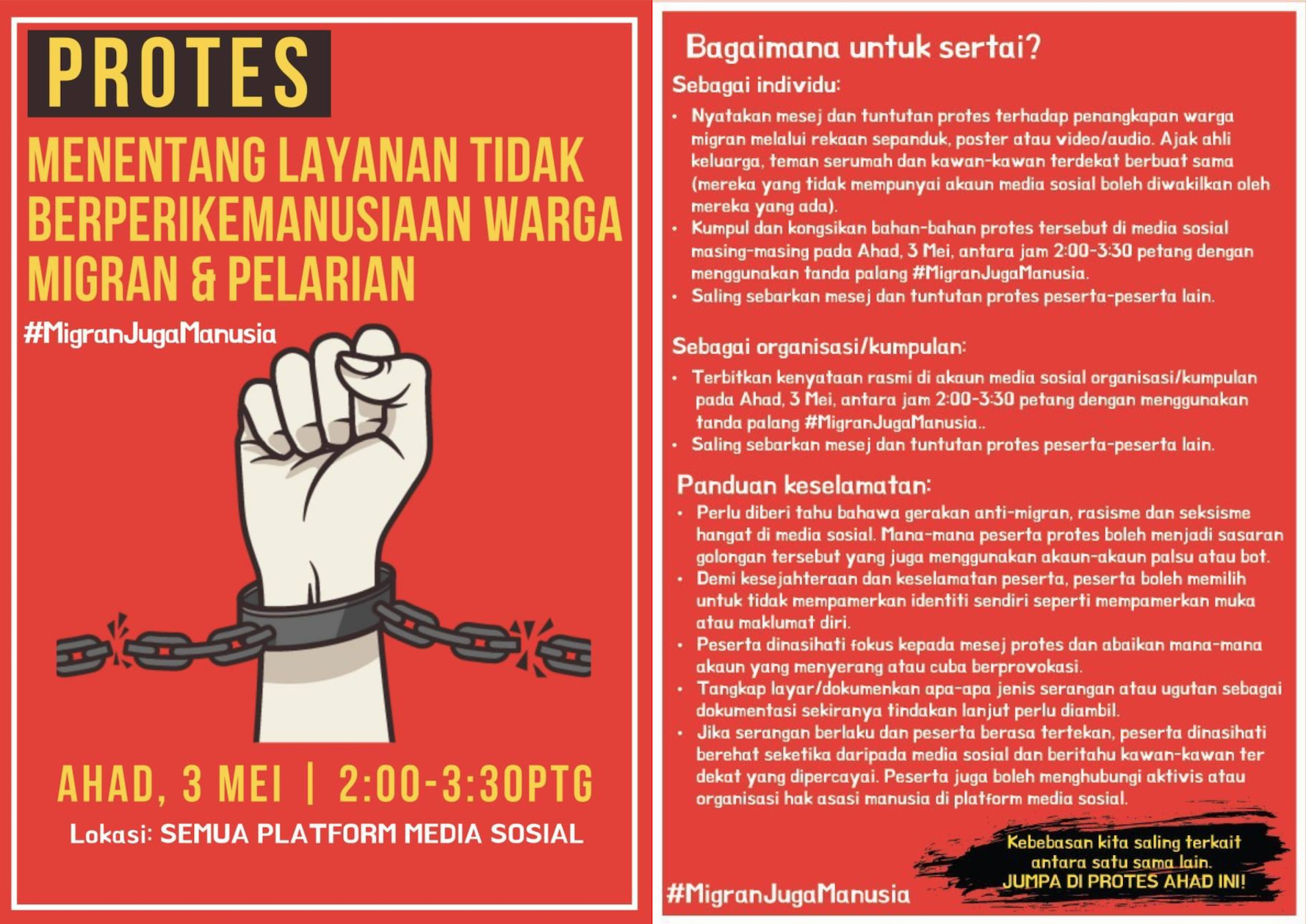

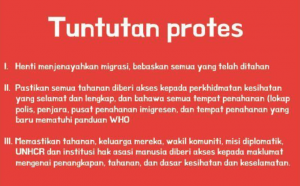

1) Stop mass arrests and to free those who have been detained

1) Stop mass arrests and to free those who have been detained