by Shaun Phuah

From the thirtieth floor of a condominium in Pudu, my friend asks, “do you see that building over there?”

“You mean the IKEA?” I ask.

“No, that one,” she points at a tall beige building with a black middle in the distance. “It’s a brothel,” she says.

I take my time and look at the building. From here, I can see its weathered paint, the green plants that climb off its balconies and onto its sides, the many air-con units that stick out along with an assortment of clothes hanging from windows that bring a flash of colour to the building’s front, hung out to dry in the afternoon heat. It looks like any other large KL building. I can’t help but think about how many other nondescript buildings across Malaysia provide similar services.

Malaysia is a constant mix of people, languages, and culture; a melting pot formed in large part due to the Strait of Malacca, a major port and passage of trade in the past and in our current day, considered one of the most important shipping lanes in the world. Through this, illicit activity and goods move back and forth between Malaysia’s borders to the countries that surround it. These illegal entities encompass things as wide ranging as drugs, to refugees, to people who have been trafficked.

Malaysia as a whole is well known for being a country that “makes no distinction between refugees and undocumented migrants.” This means on a systemic level, refugees who are already in situations in their home countries where they have found it necessary to escape are marked as groups of people who can be exploited and trafficked by organized crime. Under such organized crime which utilizes this lack of policy that surrounds refugees, it becomes nearly impossible to see the violence that happens to these legally vulnerable people until it is already too late; as the discovery of the 28 human trafficking camps and the mass graves holding 106 human bodies in Wang Kelian shows. As a further consequence of the complete lack of policy surrounding refugees coming into Malaysia, police officers themselves, with the authority they possess, freely engage with and profit off of the exploitation of migrants seeking refuge that enter Malaysia.

Aside from refugees, migrants entering Malaysia willingly also face an unprecedented degree of exploitation as the Malaysian government fails to systemically form basic rights for migrants, allowing criminal groups to take advantage of this lack of systematization.

All this culminates in a country where sex work is a massive industry that is ultimately ignored in part because of the social stigma and laws that surround it. This industry could only exist however, as a result of demand. People—both foreign and local are still engaging with sex workers despite its taboo status. The fact that sex work remains illegal has not curbed its existence in the slightest; it has instead allowed this lucrative industry to be co-opted by bad actors and instead of the police stopping sex work from happening—because of its illegal nature—corrupt police use this lack of accountability to profit from and further exacerbate the issues surrounding human and sex trafficking. Even with a complete crack down on sex work by increasing police effort and giving harsher punishments to those interacting with sex work, the industry itself will remain. There is simply too much money to be made and too much demand.

A few years ago late at night, I was standing by a quiet roadside in KL, in front of a Chinese temple still under renovation. I was out smoking shisha with a friend and we were headed back to his car to get back home. The street was covered in the dim orange light of a few street lamps and I saw a woman standing by the roadside.

She was a pretty woman with long black hair and she wore a short dress that showed her thighs. She turned around, looked at me and waved.

“A prostitute,” my friend laughed, as we got in his car and he started the engine. I could still see the woman standing on this empty road until we turned the corner.

I still think about this woman. About where she must be right now.

Knowing that sex workers face a higher degree of violence as a direct result of the work they do and how they are perceived by society, a grim image is painted of the great adversities the average sex worker in Malaysia must face.

It is easy to look at the statistics and the data surrounding sex work and to dissassociate these facts from the actual people who under varying circumstances have ended up in this line of work.

But here was the actual person, who I recognized then, standing tall on this dark roadside by herself, had a level of courage that I could not imagine. This was someone who like anyone else woke up in the morning, ordered food from shops similar to those I visit, who probably had people they cared deeply about, who ended up a sex worker for many different possible reasons and none of them out of convenience.

On an initial level, is the simple fact that what is truly being trafficked is labour. Women who are trafficked are not always trafficked entirely for the purposes of sex trafficking, but instead are trafficked to Malaysia “for forced labour as domestic workers”. Sex trafficking is simply a large branch of the giant and lucrative tree that is forced labour. The only solutions are legitimizing migrants and refugees on a systemic level within Malaysia; a tricky and complicated solution that our government is reluctant to act on as voiced by Malaysia’s deputy home minister, Dr Wan Junaidi Tuanku Jaafar as he says, “If we allow these people to start working, everybody will start coming here.”

There are no simple answers to the massive issues that surround human trafficking. However, the decision to simply ignore the issue and especially ignore it through wholesale criminalization of a wide ranging group of people only serves to empower criminal organizations and complicit government officials to profit off of and manipulate the system itself. To criminalize something does not magically allow the problem to disappear—it instead becomes deeply embedded within the system of our society as checks and balances disappear and accountability for the officials that abuse this system dissipates entirely. To create a system which legitimizes migrants and refugees is also to tackle the tools human traffickers and corrupt officials use at its very root; it also begins to tackle the very cause of sex trafficking itself.

It is a simple fact that sex work already exists and is here to stay in Malaysia, as stated earlier, it is too lucrative and there is an endless demand. Much like with the issues of human trafficking, to simply ignore the issue entirely through criminalization is to allow sex work as a whole to enter the invisible space of the underground where it becomes hard to track and hard to see; where it ends up entirely within the jurisdiction of law enforcement allowing for law enforcement to have no oversight which allows them to take advantage of and profit from the illegal industries they were tasked with preventing in the first place.

Research shows us that one powerful solution to sex trafficking is the legalization of sex work itself. This allows for sex work to be systemitized, so that checks and balances can be afforded to the industry as a whole, where not only law enforcement is involved, but an environment where social workers and other government agencies have the ability to further check up on and make sure that the sex work that is happening is within a consistently ethical context. The legalization of sex work would also decrease the amount of social stigma sex workers face and as a result, it would also reduce the violence that comes with that stigma. When proper regulation is implemented within the space of a wholly criminal industry, criminal organizations have less opportunities to exploit the people within the industry itself.

The concept of sex work in itself is a controversial one within the context of Malaysian society, in large part because of religion. However, we do not ban either alcohol or pork and we accept that different rules apply depending on the religion a person is born into and form laws accordingly; this does not mean that these industries and products are banned and made illegal by our government.

Ultimately, people are being abused and their labour is being exploited in large part because of laws that meekly criminalize groups of people and sex work itself. These are people we see on a day to day basis going out into the city, going to our local grocery stores, who pass us on the street, who take the same public transportation as us. They are still part of a wider community of Malaysia even if legally they are not recognized as such. To make life better for them is also to foster a more transparent and compassionate society that recognizes our own individual agency and the beautifully complicated personhood that exists in every person we pass on the street or eat beside in the food court or mamak.

A film like The Birth of a Nation is a product of its time. It is a film about Southern white pride and identity in an age that was moving away from the agrarian past and embracing new, progressive values. It is a film about Southern white heroism and victimhood in an age when African Americans were beginning to be recognized as free citizens. It is a film that panders to white superiority and insecurity in a time of change, arresting its audience in a freeze-frame of an escapist narrative so they can relive “better” times.

A film like The Birth of a Nation is a product of its time. It is a film about Southern white pride and identity in an age that was moving away from the agrarian past and embracing new, progressive values. It is a film about Southern white heroism and victimhood in an age when African Americans were beginning to be recognized as free citizens. It is a film that panders to white superiority and insecurity in a time of change, arresting its audience in a freeze-frame of an escapist narrative so they can relive “better” times. We do not tend to think of colonialism as a traumatic event the way we rightly think war is. But the truth is that

We do not tend to think of colonialism as a traumatic event the way we rightly think war is. But the truth is that  Mat Kilau’s narrative recognizes the incorrectness of the British stereotype against Malays while entirely leaning into similar stereotypes the British made about the Chinese and Sikhs. The Chinese character Goh Hui is a greedy, scheming and slimy character who doesn’t do anything if it does not benefit him personally, and the Sikh soldiers are violent, cruel and wholly obedient to their British masters.

Mat Kilau’s narrative recognizes the incorrectness of the British stereotype against Malays while entirely leaning into similar stereotypes the British made about the Chinese and Sikhs. The Chinese character Goh Hui is a greedy, scheming and slimy character who doesn’t do anything if it does not benefit him personally, and the Sikh soldiers are violent, cruel and wholly obedient to their British masters. Ultimately, the goal should be to get to a place where we can tell stories that reflect the true diversity of a Malaysian narrative. Until then, siloed messaging is a baby step that young, post-colonial countries live with until we feel like we’ve aired out all our trauma – Malays have always made movies for Malays, Chinese for Chinese and Indians for Indians. Of course, there are exceptions, and I would never propose foregoing the telling of individual communities’ stories in favour of some contrived muhibbah narrative.

Ultimately, the goal should be to get to a place where we can tell stories that reflect the true diversity of a Malaysian narrative. Until then, siloed messaging is a baby step that young, post-colonial countries live with until we feel like we’ve aired out all our trauma – Malays have always made movies for Malays, Chinese for Chinese and Indians for Indians. Of course, there are exceptions, and I would never propose foregoing the telling of individual communities’ stories in favour of some contrived muhibbah narrative.

Now it is time to explore the other side of the coin. Recently, the Facebook group

Now it is time to explore the other side of the coin. Recently, the Facebook group  The phenomenon is too accurately described by the film Parasite (2019) that has helped us articulate class divides during the Central Malaysia floods. Despite being in similar positions, the Kims – an art therapist,

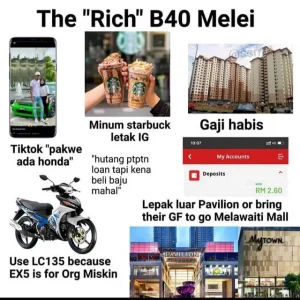

The phenomenon is too accurately described by the film Parasite (2019) that has helped us articulate class divides during the Central Malaysia floods. Despite being in similar positions, the Kims – an art therapist,  One could argue that working class subcultures like Rempit and Ah Beng have been subsumed under the larger umbrella of expressions used to mock the B40 group. Things like modified cars are immediately labelled as an indicator of someone from B40, which comes as no surprise as their group description explains that it was initially created to “memasyhurkan golongan motor ekzos bising sebagai “B40”. Tapi dikembangkan untuk merangkumi segala aspek perangai B40.” Asset ownership, such as spacious housing or luxury cars, are lifestyle indicators that are key in cementing and signalling middle-class status. [1] Thus, when the B40 group attempts to achieve the same “look” in a much more low-cost manner such as creating a bungalow out of two flats or modifying cars with loud exhausts, instead of “working hard” to accumulate money and transcend one’s class, those

One could argue that working class subcultures like Rempit and Ah Beng have been subsumed under the larger umbrella of expressions used to mock the B40 group. Things like modified cars are immediately labelled as an indicator of someone from B40, which comes as no surprise as their group description explains that it was initially created to “memasyhurkan golongan motor ekzos bising sebagai “B40”. Tapi dikembangkan untuk merangkumi segala aspek perangai B40.” Asset ownership, such as spacious housing or luxury cars, are lifestyle indicators that are key in cementing and signalling middle-class status. [1] Thus, when the B40 group attempts to achieve the same “look” in a much more low-cost manner such as creating a bungalow out of two flats or modifying cars with loud exhausts, instead of “working hard” to accumulate money and transcend one’s class, those

The Perlis mufti, on the other hand, has stated that in Perlis Islamic law the agreement to conversions were amended from “both the mother and father” to “either father or mother” in 2016. People can easily sympathise with the fact that such gaps in the law should not result in mothers being separated from their children.

The Perlis mufti, on the other hand, has stated that in Perlis Islamic law the agreement to conversions were amended from “both the mother and father” to “either father or mother” in 2016. People can easily sympathise with the fact that such gaps in the law should not result in mothers being separated from their children.

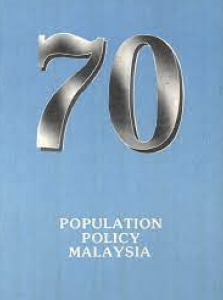

The cultural production of what it means to be a woman and mother in Malaysia is due to many factors and expectations stemming from religion, culture, history and also the nation’s interest in population control. Malaysia’s “70 million by 2100” policy adopted in 1984 has put increasing pressure on women to stay at home and nurture their children and ultimately, the nation’s future population. Scholars argue that colonial interventions on mothering in British Malaya were also done with the similar goal of securing labour for the colonial economy, given that replacing labour overseas had begun to become too costly [3]. Thus, being a mother has always been highly regarded. Invoking

The cultural production of what it means to be a woman and mother in Malaysia is due to many factors and expectations stemming from religion, culture, history and also the nation’s interest in population control. Malaysia’s “70 million by 2100” policy adopted in 1984 has put increasing pressure on women to stay at home and nurture their children and ultimately, the nation’s future population. Scholars argue that colonial interventions on mothering in British Malaya were also done with the similar goal of securing labour for the colonial economy, given that replacing labour overseas had begun to become too costly [3]. Thus, being a mother has always been highly regarded. Invoking The future of work is full of precariats. What is a precariat? It is a portmanteau of the words “precarious” and “proletariat”. Terms like “precariat” have taken on more importance with the popularity of the “gig economy”. Back in 2021, NASDAQ listed Grab Holdings Ltd, a Singapore-headquartered company. Some celebrated this, while others lamented

The future of work is full of precariats. What is a precariat? It is a portmanteau of the words “precarious” and “proletariat”. Terms like “precariat” have taken on more importance with the popularity of the “gig economy”. Back in 2021, NASDAQ listed Grab Holdings Ltd, a Singapore-headquartered company. Some celebrated this, while others lamented  Couriers for GoKilat, Gojek’s GoSend same-day delivery service, recently carried out back-to-back strikes to protest GoKilat’s new incentive scheme. The scheme proposed that couriers who once received IDR 10,000 (US$0.70) for five completed deliveries would now only receive IDR 5,000 (US$0.35).

Couriers for GoKilat, Gojek’s GoSend same-day delivery service, recently carried out back-to-back strikes to protest GoKilat’s new incentive scheme. The scheme proposed that couriers who once received IDR 10,000 (US$0.70) for five completed deliveries would now only receive IDR 5,000 (US$0.35). For instance, the J&T strikes in February 2021 were met with anger against the workers for apparently destroying customer packages and not delivering packages on time. The protest against J&T’s change in the commission system, which would reduce the wages for delivery workers, was largely overshadowed by netizens’ anger against worker attitudes. The media also began to spotlight how customers can

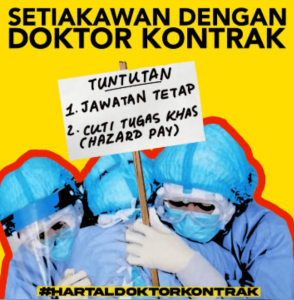

For instance, the J&T strikes in February 2021 were met with anger against the workers for apparently destroying customer packages and not delivering packages on time. The protest against J&T’s change in the commission system, which would reduce the wages for delivery workers, was largely overshadowed by netizens’ anger against worker attitudes. The media also began to spotlight how customers can  Strikes work, even in this region, even without unions. However, public support is a key element in ensuring the success of strikes. The public must want to better working conditions for gig workers. Workers can then use this solidarity as a bargaining tool. Thai, Hong Kong and Indonesian public support for strikes, as well as Malaysian support for Hartal Doktor Kontrak, illustrates this. The Hartal Doktor Kontrak strike resulted in parliament urgently debating the issue despite threats from directors of hospitals and state health departments on medical workers. At the time of writing, the Ministry of Health has promised that contracted doctors will be able to apply for specialist training under Hadiah Latihan Persekutuan.

Strikes work, even in this region, even without unions. However, public support is a key element in ensuring the success of strikes. The public must want to better working conditions for gig workers. Workers can then use this solidarity as a bargaining tool. Thai, Hong Kong and Indonesian public support for strikes, as well as Malaysian support for Hartal Doktor Kontrak, illustrates this. The Hartal Doktor Kontrak strike resulted in parliament urgently debating the issue despite threats from directors of hospitals and state health departments on medical workers. At the time of writing, the Ministry of Health has promised that contracted doctors will be able to apply for specialist training under Hadiah Latihan Persekutuan. Former Paralympic athlete Koh Lee Peng made headlines for selling tissue packets. She had been unable to secure jobs due to her disability. She mentioned that locals assumed she was part of a syndicate or that she was an illegal foreigner.

Former Paralympic athlete Koh Lee Peng made headlines for selling tissue packets. She had been unable to secure jobs due to her disability. She mentioned that locals assumed she was part of a syndicate or that she was an illegal foreigner. P

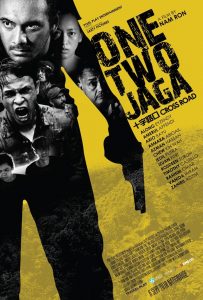

P One Two Jaga is one of the few films in Malaysia that placed corruption at the center of its subject, with story arcs of how poor wages in the police force led to corruption. The film critiqued the optimism of the police vs. villains dichotomy.

One Two Jaga is one of the few films in Malaysia that placed corruption at the center of its subject, with story arcs of how poor wages in the police force led to corruption. The film critiqued the optimism of the police vs. villains dichotomy. Take for example Malaysia’s remand system, which allows the police to apply to the Magistrate to detain anybody for longer than 24 hours for further investigation. The Magistrate can also order the police to do the same. After 24 hours, your detention period can be extended up to 14 days. At the end of the detention period, the police should release you or bring you before the Court to be charged. In theory, your relatives and lawyer should have details of your arrest and remand. However,

Take for example Malaysia’s remand system, which allows the police to apply to the Magistrate to detain anybody for longer than 24 hours for further investigation. The Magistrate can also order the police to do the same. After 24 hours, your detention period can be extended up to 14 days. At the end of the detention period, the police should release you or bring you before the Court to be charged. In theory, your relatives and lawyer should have details of your arrest and remand. However,  We end the year 2021 in Malaysia with disastrous flash floods amidst a pandemic and rising food prices. All this came on the heels of yet another cabinet reshuffle by Prime Minister Ismail Sabri. This is the year where things are put into odd perspective – ministers pose for

We end the year 2021 in Malaysia with disastrous flash floods amidst a pandemic and rising food prices. All this came on the heels of yet another cabinet reshuffle by Prime Minister Ismail Sabri. This is the year where things are put into odd perspective – ministers pose for  The problem of kleptocratic politicians and their lack of care in governing the nation always looms before the general elections, but there was always a deeply ingrained fear as a nation that race riots and conflicts would erupt and result in instability. The May 13 riots have been imprinted into our collective cultural memories and emerge like an ominous warning during every general election and mass protest.

The problem of kleptocratic politicians and their lack of care in governing the nation always looms before the general elections, but there was always a deeply ingrained fear as a nation that race riots and conflicts would erupt and result in instability. The May 13 riots have been imprinted into our collective cultural memories and emerge like an ominous warning during every general election and mass protest.

Just as these groups imagined a Malaysia on the brink of its formation that was fair and equal, we too can do so once again to bring about a change that has been far overdue. David Graeber believed that there were two kinds of imaginations: the first was “imaginative identification”, which is the ability to imagine another’s point of view to compromise and work together towards common goals. The second was “immanent imagination”, which is the capacity to imagine and bring about new social and political ways of being as we collectively decide what we want to do with our lives.

Just as these groups imagined a Malaysia on the brink of its formation that was fair and equal, we too can do so once again to bring about a change that has been far overdue. David Graeber believed that there were two kinds of imaginations: the first was “imaginative identification”, which is the ability to imagine another’s point of view to compromise and work together towards common goals. The second was “immanent imagination”, which is the capacity to imagine and bring about new social and political ways of being as we collectively decide what we want to do with our lives. Every so often, parliament will heatedly discuss an “issue” that seems to be somewhat petty, typically within the scope of race and religion and begging the question of whether we have more pressing to discuss. The Timah whiskey controversy is one such example, joining the ranks of Malaysia’s censorship of Beauty and the Beast due to the film’s LGBT character and permanently banning Beyonce.

Every so often, parliament will heatedly discuss an “issue” that seems to be somewhat petty, typically within the scope of race and religion and begging the question of whether we have more pressing to discuss. The Timah whiskey controversy is one such example, joining the ranks of Malaysia’s censorship of Beauty and the Beast due to the film’s LGBT character and permanently banning Beyonce. The Timah controversy revolves around DBKL banning alcohol in Chinese medicine halls and sundry shops. Tangga Batu MP Rusnah Aluai compared the consumption of Timah whiskey to “drinking Malay women”, as the name alludes to Kakak Timah, Mak Timah and Mak Cik Timah. This comparison was made during the debate session on the Trade Descriptions Bill (Amendment) 2021 on 28 October. Ten days before this, the

The Timah controversy revolves around DBKL banning alcohol in Chinese medicine halls and sundry shops. Tangga Batu MP Rusnah Aluai compared the consumption of Timah whiskey to “drinking Malay women”, as the name alludes to Kakak Timah, Mak Timah and Mak Cik Timah. This comparison was made during the debate session on the Trade Descriptions Bill (Amendment) 2021 on 28 October. Ten days before this, the